Excerpt

Excerpt

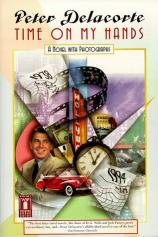

Time On My Hands

Chapter 1 From: Time On My Hands

I have some time on my hands. There is no better way to describe my situation. As I write these words -- whose writing may turn out to be an act of utter self-indulgence -- I sit at a rustic table in a primitive cabin in the woods outside Corvallis. Having spent virtually every day of my life in one city or another, I must tell you it is strange and quite lonely here, that I feel utterly out of place, that my only solace is in knowing soon, one way or another, I'll be leaving.

I should tell you an important thing about myself. I don't wish at this early juncture of the story to seem ostentatious, but as a child I had a very clear sense that I was destined to do something exceptional. There was never a specific vision: I didn't daydream about becoming president or discovering a cure for cancer. I was just a well-balanced boy who had (considering that I had no parents) a fairly normal, happy childhood, during which I strongly felt something singular was in store for me.

A memory has come bouncing into my head this minute, a moment I hadn't recalled in twenty years at least, and now it's such a vivid picture that it gives me chills. I see myself at age ten, the one summer I spent at camp, in Maine, and the eight of us in my cabin, plus two counselors, were on a three-day canoe trip. We paddled like galley slaves up one lake and down another, what seemed like sixteen hours a day. We paddled through rainstorms and blazing hot August afternoons. Wherever it was we were trying to reach, we got there, and on our third night we spread our sleeping bags on an island somewhere close to Canada, under a sky that contained far more than the usual contingent of stars. We city boys ravenously consumed our canned swill, after which the traditional swapping of ghost stories around the campfire was supplanted by an epidemic of falling asleep.

I did not sleep. I had found a strength in myself. I had never complained during this little ordeal, unlike my fellows. I had taken extra shifts at the bow position in my canoe, had found myself growing stronger as we'd glided toward the twilight. Now, filled with exhilaration, I walked among the fallen, the seven boys and the two adolescents, under that magnificent chandelier of a sky, and I realized that I alone was seeing what I saw. In this recognition I did not exclude only the nine unconscious human beings nearby, but all the rest of the world. I was at that solipsistic instant the absolute center of the universe, aged ten.

To call the moment an epiphany would be to understate. To recall it merely as solipsism would be to do my ten-year-old self an injustice. I did not, after all, suspect even for a second that I was God, or even related to God. I had simply discovered the fact that if some beast came out of the woods and did away with me, or if by any other means I suddenly ceased to exist, then so too would all I surveyed. I had stumbled across my importance.

It was not a thing I dwelt upon over the years, nor was it something I chose to tell anyone, especially not the aunts who raised me rather diffidently. It was something I suspected other children, at least those of my acquaintance, had not experienced. I did quite well in school, went away when I was sixteen to a boarding school whose reputation far outstripped its proficiency at educating, but nonetheless I made the progression to the next level, to a famous university in New Jersey. Here again I did well, although not spectacularly.

I was never terribly popular, which I like to think was a phenomenon of my own choosing. I could be charming and ingratiating when I needed to be, but I seldom needed to be. I was content with a small circle of friends. I had no trouble getting dates, and when I wanted to sleep with a woman it was usually only a matter of time before we did. If I never sustained a relationship, it was again because I chose not to.

What difference does any of this make to you? I suppose that if you're to have any understanding of what's to follow, you should possess at least a minimal portrait of its author. My urge is to gather up everything we might loosely call exposition, to make it as succinct as possible, and set it down right at the start. But do I have the time? Do I have the space? Even if so, will you ever see it?

It is better, I think, to jump forward (quite a ways forward, from my present perspective) to a more pertinent moment in my story.

I was in Paris. It was the first week of May, 1994. I was working. There is a man in Seattle named Harvey Wells Greenglass who some years ago devised a sort of new-age guidebook. If you've traveled to any number of cities in Europe and the United States and if you're of a certain class and sensibility, you're probably familiar with the Greenglass Entrée series. Greenglass books are small and good-looking, they cover traditional touristic attractions minimally, often with some irony, but they excel in taking the visitor to all manner of places he won't find in other guidebooks. To a church almost as spectacular as the one everyone else is gawking at, but off the beaten track. To restaurants every bit as good as Michelin's latest pet, but not nearly as expensive or crowded. To bistros, bars, stores, neighborhoods, nightclubs, zoos, theaters, subway stops that offer something out of the ordinary.

Greenglass came up with the Entrée concept. He has relied on others to do all the research, all the writing, all the editing, all the production. You will find Greenglass's name in quite conspicuous print on the front of every Entrée book. You will find the names of people who've done all the work in the very back of the book, in tiny print. You will find my name -- or shall I say that one used to be able to find my name -- in the back of the original Entrée to Paris and in all three updates.

Thousands of Americans and other English-speaking travelers have carried that little book around Paris for days or weeks, have paid homages to Harvey Wells Greenglass at every eccentric little shop, every out-of-the-way outdoor market they would otherwise have missed, while the fat old philistine himself has probably never seen more of Paris than his suite at the Ritz.

I don't intend to seem bitter. If there is a strong element of injustice here, I can't dwell on it terribly long when I consider the positive aspects of my association with Entrée: they paid me generously, they reimbursed my expenses promptly, down to the last centime, they edited my work minimally, diligently. And of course every other year they sent me to Paris for a couple of months.

Had you been able to see my Entrée to Paris, you'd know the love I have for the city. I lived there briefly, in my twenties. I imagined I would stay there forever. Each day was a new discovery: new places to eat, to browse, to shop, to stop and stare in astonishment at some beauty, physical or metaphysical. I found after six months that I was getting nothing done. It was as if I had set myself the task of organizing my room, and I proceeded to do so with vigor and passion until everything was in fine shape, and then the following week I took it apart and started over again. Much room organizing. Terrific ideas. But once the room is done, there must come a time to use it.

I am goal oriented. Is it altogether fatuous to say that? Is it unnecessary, superfluous, redundant? I was so extraordinarily happy, and yet at odd moments I would be overcome by attacks of piercing anxiety, thinking My God, if I stay here I'll never get anything done!

So I left Paris, moved back to New York, became an editor, lived my life, got things done, to no great satisfaction. I quit my job, left New York when I was twenty-nine, moved to Los Angeles in part because there was a woman who fascinated me. That did not last. Lovelorn, I took a long trip to Turkey and Bulgaria, wrote some pieces about it that grew into a book. The book did not do particularly well commercially, but it found a certain audience that eventually included Harvey Wells Greenglass. And nine years after I left Paris, I was back -- doing precisely what I'd done as a directionless twenty-four-year-old, but getting paid for it now.

Let me then duly note the passage of another nine years. The Paris Entrées weren't all I did in that period. A book on Australia, emphasis on vegetation and beer; a book on Quebec, a curious mixture of gourinandise and politics, the latter perhaps because I spent much of my Canadian spring and summer in the apartment of Marie-Laure, exquisite epicurean daughter of a separatist icon. She accompanied me to the West Coast: to Vancouver, to Seattle, where she charmed Greenglass out of his Birkenstocks. In my house in Santa Monica I told her I loved her. I'd never said those words to anyone. I was forty-two years old.

She said, "Why do you love me?"

It was not the response I'd anticipated, certainly not the one I'd hoped for. For what seemed like a geological era I said nothing, and then I stammered and halted and lurched. What I said, if I can recall with any definitude, was that I knew I loved her because she was the first woman I'd ever needed to tell I loved.

I recall her next words exactly. I have such a clear picture of us in my kitchen, her leaning against the dishwasher. She said, "Well, then I love you too."

This is of course not the "pertinent moment" I referred to some pages ago, although it is undeniably a moment that leads to that moment. Because if Marie-Laure had not accompanied me to Paris, this rather unlikely series of events would never have occurred, and instead of writing an antememoir for you, I would probably be sitting in a seedy hotel in Vladivostok, or the only European restaurant on Madagascar.

She came with me, and for a time we were in heaven. It's still not clear to me when things started to go wrong. We bustled from one side of Paris to the next, from arrondissement to arrondissement. She participated in the process; more than once we had a meal or a drink in some unlikely establishment simply because Marie-Laure had noticed it. For my part, I wondered how I'd managed all those hundreds of previous Parisian sorties on my own. How many times had I sat in the corner of a new bistro, at a table for one, subsisting on interior conversation? How much more pleasurable was it to eat the same meal, to share the same discovery, with someone I loved?

The alteration of my social life was considerable. I had been in the habit of looking up three or four American acquaintances during my visits to Paris. Now I was visiting fifth-floor walk-ups off Boulevard St. Michel, taking part in earnest discussions of philosophical ethics and the relative skills of Jean Renoir and Steven Spielberg until four in the morning, waking up at eight to discover my only clean set of reconnoitering clothes still stinking of stale marijuana smoke. It was exciting. It was rather like being back at college. Marie-Laure, of course, was only eight or so years removed from college.

The difference in our ages was not something that concerned me a great deal. For one thing, these evenings were attended by plenty of graybeards, so it wasn't as if I stood out. For another, I have always looked uncommonly young. It was a mild but flattering inconvenience, on the infrequent occasions that I found myself buying alcohol, to be asked for proof of age well into my thirties. At forty-two, I think I could easily have passed for thirty-five.

I would say I am a good-looking man: slightly under six feet tall, with light brown hair and blue eyes, with modest, well-formed facial features. I keep myself in good condition. I weigh, I believe, a pound or two less than when I entered college.

Marie-Laure struck me at first as being only beautiful. The more time I spent with her, the more I became convinced she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. She had inherited from her swarthy father brown eyes and a permanently tan skin tone, from her Nordic mother luminous blond hair. Perhaps three inches shorter than I, she was exquisitely proportioned, with the sort of figure that caused men to stop and stare abjectly.

Jean-Luc Mouchard was an academic and a small-time critic, a major figure in Marie-Laure's group, which I came to think of as the Moveable Snack. He was lean and balding, with a pitted face and an irritating manner, strident and self-righteous. It was my impression that Mouchard shaved about every third day, that be bathed about half as often as he shaved, and experienced a lucid thought a third as often as that. Here was the man who took Marie-Laure away from me.

I will not bore you with vignettes of her duplicity. I believed her when she began begging out of our midday meals because she was "gaining weight." I accepted each excuse when she was twenty, thirty, forty minutes late for our afternoon appointments. Until finally she did not appear at all, and I was forced to confront her, and she confessed to me the whole sordid matter. Mouchard, on top of everything else, was married, was father to three children. This, Marie-Laure whispered to me in depressed, penitent tones, was of great concern to her.

She moved out of our room, into the love nest she shared with her scrawny freak. I had barely uttered a word. I had three weeks remaining in Paris, three weeks of all-expenses-paid investigation, three weeks anticipated as pure pleasure, and suddenly I was in shock, deserted, devastated, sleepless, torn asunder, miserable.

I spent the following morning as if heavily anesthetized, sitting in my room with the television playing a succession of otherworldly programs, including an American situation comedy that, judging from the bell-bottoms and the excessive hairdos, dated from the mid-1970s. Whatever it was, I had managed to miss it during its currency, and now this unattractive ensemble was murmuring to me, twenty years later, in badly synchronized French. I drank cup after cup of room-service coffee, trying to propel myself out of the funk. I made occasional attempts to read my daily copies of Le Monde and the Herald Tribune but my concentration span seemed limited to about five seconds.

Trips to the window revealed a gruesome day, a regression toward winter: a gray sky, a steady rain, pedestrians bundled and huddled against the wind. I had already missed my morning visit to the Musée de Cristal, a fairly long Métro ride away. Given the circumstances, I decided that departing from my schedule might be therapeutic, that diverging from my frugal pattern this once wouldn't put too large a dent in the Greenglass pocketbook. I bad the concierge call a taxi.

Lunch at a beloved café on the Rue St. Martin hardly cheered me up; I could think only of how much Marie-Laure would have enjoyed the place. When the rain briefly abated to drizzle, I walked several blocks up the street to the Musée National des Techniques, my favorite of all of Paris's little museums. I use the word "little" simply to differentiate these places from the Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay and the other monsters. The Musée des Techniques (the National Technical Museum) is fairly spacious, just the proper size to provide an afternoon's pleasant survey, or several days getting a true sense of the place.

It is a cornucopia of machines. It is as if someone with a few screws loose had been handed a few million francs, had been assigned the job of accumulating a certain number of machines that would (first) fill the space provided in a proper esthetic manner, and (second) illustrate the history, the development, the evolution of machinery in a properly French manner. Thus there seems as much emphasis on the wrong turns of technology, on various baroque solutions to eigheenth- and nineteenth-century agricultural and industrial problems, as there is on their more efficient and recognizable brethren. This museum could not exist in Germany.

On the main floor one is invited to weigh oneself on a scale that is connected to a laughably out-of-date computer/printer. One may then discover, by pressing the requisite buttons, how much he would have weighed in various European cities four hundred years ago, when each had a very different notion of what a "pound" was. Thus you may have weighed 150 in Bologna, but 175 in Berlin. The point is to show how much clearer things have become by virtue of standardization, of the metric system. But one gets the impression, holding the faint dot-matrix printout, that the Musée des Techniques is more than a little wistful about progress.

So I had for the fifth time in twelve years completed my chronological tour of mechanical history, and I was beginning to dread the conclusion of my visit, wondering where I was bound next, and how I would see myself through a second post-Marie-Laure night. But I knew I had the basement still to go. The basement, in the best departent-store tradition, is where the Musée des Techniques keeps all the bargain stuff, everything it doesn't know what to do with. There are all sorts of ancient bicycles and motorcycles and a few automobiles, a racing car, and other means of propulsion gone by the wayside.

Near closing time, I wandered toward the end of my final aisle, coming across a final assortment of undocumented pieces, evidently new arrivals. A tall, gaunt man who appeared to be in his late sixties or early seventies was raptly examining one of these objects. His appearance was striking: he was perhaps six feet six, his ivory hair arranged in ponytail. He wore a brown leather jacket that looked as if it had survived the Battle of Britain, black leans, and green cowboy boots. He caught my eye. "Ce truc lá," he said with a distinctly American accent, "à votre avis, c'est quoi?"

He had asked me what I thought the unlabeled object was. His French, but for the accent, was colloquial and right on the money. I as much more intrigued by him than by the curious machine in question. I said, "I'd taken you for a local."

"As opposed to what? An express?" He guffawed, and the sound echoed through the enormous room. He took a step toward me then, and I took a reflexive step backward, wondering if I'd encountered a madman. "I'm sorry," be said. "What made you think I was French?"

"The look," I said. "Especially the boots."

He grinned at me. "What could be more American than cowboy boots?"

"Yes, exactly," I said.

"Ah, I see." He nodded. "We're talking paradoxes here, aren't we? You took me for a Frenchman because I'm wearing American shoes. I took you for a Frenchman because you're wearing French shoes." Indeed I was: French loafers, in a gray suede, chosen by Marie-Laure. "It just shows you how deceiving the simplest things can be, doesn't it? Which brings me back to this machine. What do you suppose it is?"

I took my first good look at the thing on the floor. What sprang to my mind was that it was a device for gliding across water. It was about three feet long, two feet wide at its broadest, with what was definitely a seat, a padded leather (or synthetic) seat projected up from its center. It was rather generally wing shaped, broad at the front, tapering off at the back. There was what appeared to be a set of controls at the front, just below an area roughly analogous to the dashboard of an automobile, and on the dashboard itself were several little protrusions that might have been gauges of some sort. It seemed, above all, neither new nor old. Other than the leather or vinyl seat cover and the glass or plastic gauges, it was difficult to discern what this thing was made of. It appeared to be metal, but it might well have been something else -- fiberglass, or some higher-tech equivalent.

I said, "It looks like a miniature boat, a jet-ski with its skis removed."

"Not bad." He grinned again. "Quite ingenious. Yes, I could see that. But it's sort of top-heavy, isn't it? Don't you suppose it would tend to flop over on itself?"

"I have no idea," I said. "I know absolutely nothing about seaworthiness, or aerodynamics. Or physics, for that matter."

"You've been here quite a while, though," the old man said. "There must be something about science that interests you."

How did he know bow long I'd been in the museum? If he'd been aware of me, how could I possibly have missed him? I said, "You've been watching me?"

He gave a short burst of laughter. "Hardly, my friend. I've been aware of you. I'm always impressed by someone who takes notes in a place like this. There's so much to learn, so much to know, but most people experience it as a freak show, an entertainment."

"It is, after all..."

"Of course it is. But it shouldn't be treated like a television show. What do you think most of them..." He made a sweeping gesture with his right hand, apparently referring to our fellow museumgoers, when in fact we were virtually alone here in the basement. "What do you think they'll recall from this visit -- Foucault's Pendulum, or how much they would have weighed in Strasbourg in 1714?"

In my case, undoubtedly the latter. "I'm sure it depends entirely on the individual visitor."

The old man nodded. His nod, as everything else about him, was quite intense. "All right, then," he said, "what are you doing here? Why are you walking around with that notebook?"

"Because it's my job. I'm doing a Paris guidebook update."

"Ah," he said, "a tastemaker. A trailblazer."

"To a degree." He must have been moving gradually closer to me, because I kept craning my neck until I must have resembled an open Pez dispenser.

"And I would venture to say, a despondent trailblazer. Am I right?"

It struck me as unnecessarily cruel that having lost Marie-Laure to the ungainly Mouchard, I should immediately afterward be waylaid by a preposterously tall psychic madman. But I bad no power to resist. "You could say that."

He said, "Let's get out of here. Let a concerned countryman buy you a drink. What do you say?"

Indeed, what could I say?

At the corner of Rue de Réaumur and Avénue de Sébastopol was a café called Le Capitole. I remember thinking at the time how strange it seemed to sit down in a place that wasn't on my list, that hadn't been recommended by a friend, an acquaintance, or a reader. I made a note to myself that I must still maintain a fraction of my critical eye, just in case there was something remarkable about Le Capitole. There was not, save that it was the location to the most important conversation of my life.

His name was Hudnut. Jasper Hudnut, formerly of Oregon State University, formerly of the Max Planck Institute, formerly of the California Polytechnic Institute at San Luis Obispo, among other places. He was, nominally, a quantum physicist. He was seventy-two years old, and a single man. He had no children and virtually no possessions. Once he'd gotten this far in his biography, he inquired as to my politics.

The rain had stopped, and most of the café's patrons occupied several sidewalk tables under the blue-gray late afternoon sky. Hudnut and I had the inside all to ourselves. "My politics?" I responded.

"It's not a difficult question, is it?"

"Rather general, though. I mean, what do you want to know?"

"Do you vote?"

"Yes. Always."

"Good. Tell me, if you would, how you voted in the presidential elections of 1980 through '88."

I had to calculate for a moment. "Carter," I said. "Then Mondale, then Dukakis."

Hudnut took a small drink from his enormous mug of beer. "If you had to sum up the presidency of Ronald Reagan in a few words," be said, "how would you do it?"

"How few?"

"Twenty seconds' worth."

"Well, I suppose I'd quote François Mitterrand. He and Pierre Trudeau were meeting with Reagan, God knows what year, God knows what occasion, and Reagan told Mitterrand some daffy anecdote, some fantasy from his past. And afterward Mitterrand, who was of course nearly as old as Reagan but quite a bit more together, came up to Trudeau and said, 'What planet is that man from?'"

Hudnut burst into laughter -- great spasms of laughter, until tears poured down his cheeks. Eventually he got control of himself and he said, "Oh, that's wonderful. I'd never heard that one before."

"What's this about?" I said.

"I think my favorite moment," Hudnut said, as if he hadn't heard my question, "was the business with the president of Liberia. His name was Samuel Doe, and Reagan's introducing him at a dinner or some such, and be refers to him as 'Chairman Moe.' It's such an extraordinary, profound moment, because it brings so many things into play. I mean, here's Reagan with his kind of African leader -- a dictator who's killing people left and right, the only reason we love him is he's not a Communist -- and not only can't he get Doe's name right, but he confuses him with a Chinese guy who happens to be synonymous with Communism. So what can you make of that? We know that all black people looked alike to Reagan, but apparently black people and Chinese people were completely interchangeable."

"Mr. Hudnut..." I began.

"Call me Jasper," he said.

"Why are we sitting here in Paris, trading Ronald Reagan stories? What's the point? What do you care about my politics?"

"Gabriel," he said, "could I suggest that you lighten up? Maybe I'm just making conversation, and not doing such a bad job of it. We've discovered a fertile common ground, I'd say. Or maybe if you weren't so damned depressed you wouldn't even be asking a question like that. Why shouldn't I be interested in your politics? You're a well-educated, talented man who's been all over the world. People depend on your wisdom for the two most important weeks of their year."

"Not on my politics."

"It's all of a piece, though, isn't it?"

Was it? Hudmit's flattery was sinking in, abetted by my second Pernod. I said, "I have no idea what you mean by that."

"Gabriel, please. I have to admit I'm not familiar with your books, but I do firmly believe that a certain mentality speaks to a certain mentality. I'm not saying there are absolutely no dull-witted rightwing Americans carrying your book around Paris, but I'd bet they're in a distinct minority."

"Of course. But that's a cultural phenomenon that has nothing to do with me. I was hired to write a book for a specific audience..."

"And what kind of audience is that?"

"Well-educated, sophisticated. People interested in broadening their horizons a bit, people who might not be attracted to the usual touristic crap."

"There you go," said Hudnut. "I rest my case."

I was not altogether sure what he was talking about. There didn't seem to be a great deal of logic involved, but for the moment it didn't matter. The old man's rather odd charm was doing its job: I was aware that he was working on me, trying to elevate me from my funk, and I didn't care.

"I think it's truly propitious that we met today," he said. "It's the sort of thing that almost makes one believe in a Higher Force."

"You're getting a little carried away, aren't you?"

"Not at all. I'm thinking how marvelous it is that I've found myself a travel expert who seems to be footloose and fancy-free."

"Footloose, perhaps," I replied, "but I'm not so sure about fancy-free. And why is it so marvelous that you've found a travel expert in the first place?"

"Now that you mention it, I've always wondered about that. Wouldn't 'fancy-free' mean lacking fancy, devoid of fancy? That's to say, wouldn't 'fancy-free' tend to be the exact opposite of 'footloose?'"

"Yes, except I don't believe it means one is free of fancies. It's the other way around, isn't it? 'Fancy' modifies 'free,' so it's a way of saying one is particularly free."

"But that would hardly be you," Hudnut said. 'At this very moment you are undoubtedly footloose, but you're utterly without fancy, am I correct?"

"Yes, I suppose. Or close to it. But please tell me why it's so important that you've found me."

Hudnut raised both his hands, urging patience on my part. "Let me provide you with a fancy. Does the name Arturo Toscanini mean anything to you?"

"Of course. One of the great virtuoso conductors. Led every famous orchestra at one point or another."

"Excellent," Hudnut said. "Now, did you know that when he was quite young, Toscanini killed a man in Italy?"

"I didn't know that," I said, "and I don't believe it's true. I know a fair amount about Toscanini, and I'd suspect that you've been misinformed."

"It was a crime of passion," Hudnut said. "There was a scandal. Toscanini was put on trial for murder -- "

I interrupted. "Where was this?"

"Parma, of course."

I knew that Parma was Toscanini's birthplace. Hudnut resumed: "He was put on trial, and he was found guilty. He was sentenced to death -- "

"This is nonsense," I said.

"It happened that the means of execution in Italy was a very primitive form of electrocution -- "

"Please," I said, "this would have been sometime in the eighteen eighties."

Hudnut brushed aside my objection without losing his rhythm. "A very primitive form of electrocution. They would lay you down in a shallow bed of water, with electrodes attached to you, and pull the lever. When it worked, when it went smoothly, it was very humane, very efficient, you got sizzled right up. But this was Italy, of course, so the technology was a lot more ambitious than it was competent. They put Toscanini in this contraption, pulled the switch, and nothing happened. They tried it again, and they singed his eyebrows a little. They sent him back to his cell, gave him a meal, zapped him again a few hours later, no luck. Finally they just let him go. Word had got around, of course, so Toscanini was besieged by the press when he got out, and everyone was asking him what happened, how had be survived several thousand volts surging through his body. And Toscanini said, 'Well, I must not be a very good conductor.'"

"That's awful," I said. "That's terrible."

Hudnut grinned at me. "But a fancy nevertheless."

I had always had mixed feelings about the hotel named L'Hôtel. It was in my favorite section of Paris, in the sixth arrondissement, where I always stayed unless testing a hotel elsewhere. It was five minutes from the Seine on a swank little street called Rue des Beaux Arts, a brisk walk from my lodging of the moment. I had never actually stayed there because, at somewhere between a hundred fifty and two hundred fifty dollars per night, its rooms were well beyond my readers' budgets, and had I had the audacity to put such an extravagance on my expense account, Harvey Wells Greenglass would certainly have underlined it in blue pencil and written WHY? in the margin. Over the years I had spent five or six evenings in L'Hôtel's bar, however, and invariably espied at least one, often several young show business types, American or British, male or female, sometimes with entourage, sometimes without. It was an excellent place to be seen.

It was also, to my bemusement, Hudnut's hotel. When he'd invited me for lunch after our third drink the evening before, I'd said, "You feel the need to mingle with the jet set?" And Hudnut had replied, "I've been staying there for thirty years, before any of the goddamn Rolling Stones ever heard of the place."

His room was on the fifth floor, triple the size of my ninety-dollar-a-night postage stamp. He was as hearty and effusive as earlier, and I must say I was feeling quite a bit more chipper, in part because I'd just had a stimulating twenty-minute walk along Parisian streets on a bright spring day, but mainly and undeniably because Hudnut had cheered me up.

We sat across from each other at a small table made of some lustrous hardwood. L'Hôtel did not to my knowledge have room service, but Hudnut had somehow managed to provide us with an elaborate salad of crisp greens, bits of marinated chicken, and tomatoes as fresh and luscious as if we were in the height of summer. He said, "Of course you know Oscar Wilde died here."

"Of course I do. Manet was born across the street, and if you were to draw a three-hundred-meter radius from this spot, you'd create an area lived in or visited by about every great artist, writer, or composer since the middle of the seventeenth century."

"You don't miss a trick."

"I don't. It's my job."

"You absolutely love all this stuff, don't you?"

"Which stuff? Paris? History?"

"Both of those. But I guess I'm mainly thinking about travel. What is there about travel that fascinates you so much?"

"I don't think I'm that different from everyone else. Why are there hotels all over the world? Why do the airlines and the cruise ships stay in business?"

"But not everyone's a fanatic," Hudnut said. "Not everyone devotes his life to wandering around the world."

To be sure, this was something to which I'd given a fair amount of thought over the years. I said, "I suppose I'm the sort of person who's never done terribly well staying at home. I suppose I'm happiest when I'm on the move, when I'm taking in new sights, when I'm learning."

"Always moving forward?"

"Not always. I think I'm happiest when I come back here. The combination of the familiar and the exotic. I probably know more about Paris than a lot of natives, but I'll always be an outsider here, a visitor, as often as I come. In a sort of perverse way, that appeals to me."

Hudnut impaled a final wedge of tomato on his fork, waved it briefly as if it were a tiny flag, and devoured it. "Gabriel," he said, "there's something we need to discuss."

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Excerpted from Time On My Hands © Copyright 2012 by Peter Delacorte. Reprinted with permission by Vintage. All rights reserved.

Time On My Hands

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Scribner

- ISBN-10: 0671023241

- ISBN-13: 9780671023249