Excerpt

Excerpt

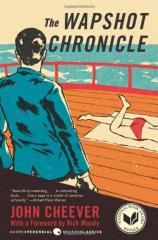

The Wapshot Chronicle

Chapter One

St. Botolphs was an old place, an old river town. It had been an inland port in the great days of the Massachusetts sailing fleets and now it was left with a factory that manufactured table silver and a few other small industries. The natives did not consider that it had diminished much in size or importance, but the long roster of the Civil War dead, bolted to the cannon on the green, was a reminder of how populous the village had been in the 1860s. St. Botolphs would never muster as many soldiers again. The green was shaded by a few great elms and loosely enclosed by a square of store fronts. The Cartwright Block, which made the western wall of the square, had along the front of its second story a row of lancet windows, as delicate and reproachful as the windows of a church. Behind these windows were the offices of the Eastern Star, Dr. Bulstrode the dentist, the telephone company and the insurance agent. The smells of these offices -- the smell of dental preparations, floor oil, spittoons and coal gas -- mingled in the downstairs hallway like an aroma of the past. In a drilling autumn rain, in a world of much change, the green at St. Botolphs conveyed an impression of unusual permanence. On Independence Day in the morning, when the parade had begun to form, the place looked prosperous and festive.

The two Wapshot boys -- Moses and Coverly -- sat on a lawn on Water Street watching the floats arrive. The parade mixed spiritual and commercial themes freely and near the Spirit of '76 was an old delivery wagon with a sign saying: GET YOUR FRESH FISH FROM MR. HIRAM. The wheels of the wagon, the wheels of every vehicle in the parade were decorated with red, white and blue crepe paper and there was bunting everywhere. The front of the Cartwright Block was festooned with bunting. It hung in folds over the front of the bank and floated from all the trucks and wagons.

The Wapshot boys had been up since four; they were sleepy and sitting in the hot sun they seemed to have outlived the holiday. Moses had burned his hand on a salute. Coverly had lost his eyebrows in another explosion. They lived on a farm two miles below the village and had canoed upriver before dawn when the night air made the water of the river feel tepid as it rose around the canoe paddle and over their hands. They had forced a window of Christ Church as they always did and had rung the bell, waking a thousand songbirds, many villagers and every dog within the town limits including the Pluzinskis' bloodhound miles away on Hill Street. "It's only the Wapshot boys." Moses had heard a voice from the dark window of the parsonage. "Git back to sleep." Coverly was sixteen or seventeen then -- fair like his brother but long necked and with a ministerial dip to his head and a bad habit of cracking his knuckles. He had an alert and a sentimental mind and worried about the health of Mr. Hiram's cart horse and looked sadly at the inmates of the Sailor's Home -- fifteen or twenty very old men who sat on benches in a truck and looked unconscionably tired. Moses was in college and in the last year he had reached the summit of his physical maturity and had emerged with the gift of judicious and tranquil self-admiration. Now, at ten o'clock, the boys sat on the grass waiting for their mother to take her place on the Woman's Club float.

Mrs. Wapshot had founded the Woman's Club in St. Botolphs and this moment was commemorated in the parade each year. Coverly could not remember a Fourth of July when his mother had not appeared in her role as founder. The float was simple. An Oriental rug was spread over the floor of a truck or wagon. The six or seven charter members sat in folding chairs, facing the rear of the truck. Mrs. Wapshot stood at a lectern, wearing a hat, sipping now and then from a glass of water, smiling sadly at the charter members or at some old friend she recognized along the route. Thus above the heads of the crowd, jarred a little by the motion of the truck or wagon, exactly like those religious images that are carried through the streets of Boston's north end in the autumn to quiet great storms at sea, Mrs. Wapshot appeared each year to her friends and neighbors, and it was fitting that she should be drawn through the streets for there was no one in the village who had had more of a hand in its enlightenment. It was she who had organized a committee to raise money for a new parish house for Christ Church. It was she who had raised a fund for the granite horse trough at the corner and who, when the horse trough became obsolete, had had it planted with geraniums and petunias. The new high school on the hill, the new firehouse, the new traffic lights, the war memorial -- yes, yes -- even the clean public toilets in the railroad station by the river were the fruit of Mrs. Wapshot's genius. She must have been gratified as she traveled through the square.

Mr. Wapshot -- Captain Leander -- was not around. He was at the helm of the S.S. Topaze, taking her down the river to the bay. He took the old launch out on every fine morning in the summer, stopping at Travertine to meet the train from Boston and then going across the bay to Nangasakit, where there were a white beach and an amusement park. He had been many things in his life; he had been a partner in the table-silver company and had legacies from relations, but nothing much had stuck to his fingers and three years ago Cousin Honora had arranged for him to have the captaincy of the Topaze to keep him out of mischief ...

Excerpted from The Wapshot Chronicle © Copyright 2003 by John Cheever. Reprinted with permission by Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

The Wapshot Chronicle

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial Modern Classics

- ISBN-10: 0060528877

- ISBN-13: 9780060528874