Excerpt

Excerpt

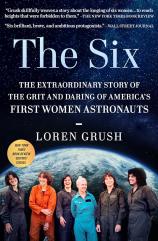

The Six: The Extraordinary Story of the Grit and Daring of America's First Women Astronauts

CHAPTER 1

But Only Men Can Be Astronauts

The sun was still hours away from coming up that morning, and Margaret “Rhea” Seddon was already staring into the open abdomen of a patient on her operating table. As per usual, she was trying to control the patient’s blood flow and repair the damage to his organs, caused by a bullet that had violently ripped through his gut. By now, she’d become used to such grisly sights. As a surgical resident in John Gaston Hospital’s emergency room, she saw all manner of gruesome gunshot and knife injuries, often the result of two angry men and too much beer. EMS crews would wheel into the John—as the doctors called their hospital—the victims of these bar brawls, typically in the middle of the night, and they’d become Rhea or some other doctor’s priority for the rest of the evening. Each night, the John’s emergency room would see so many trauma patients that it would earn an even more menacing nickname: the pit.

Sometimes Rhea stanched the blood and sewed people up just fine; other times she just couldn’t repair the sheer amount of damage. Those moments were the most devastating. This early morning, however, things seemed to be progressing well, and she eventually stitched up her patient, sending him off to the ICU. Her work wasn’t done, though. As the patient’s doctor, she still had to keep her eye on him in case some unforeseen complication popped up. So she headed to the doctors’ lounge, which sat adjacent to the ICU.

It was hard for her to believe, but there’d been a time when her presence in the doctors’ lounge would have been a serious transgression. When she’d been a surgical intern at Baptist Memorial Hospital, across the street from the John in Memphis, Tennessee, she’d been barred from entering the doctors’ lounge. It was for “men only,” and she was the only woman surgical intern at the time. The head doctor told her the reason was that sometimes men walked around in their underwear in the lounge. She told him it didn’t bother her, but he said the men would be embarrassed. Her superiors told her she could wait between surgeries in the nurses’ bathroom. Rhea tried to change the policy, but she lost out and found herself taking naps on a foldout chair in the bathroom, with her head resting against the wall. The rule had prompted her to switch to the John for her residency—a place that didn’t cling to such sexist policies.

Ever since she’d decided to go into medicine, Rhea always seemed to be out of her comfort zone in some way. She’d grown up in a completely different world: a small girl with straight blond hair in the upper-middle-class suburban town of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. There, she followed the standard recipe for How to Make a Proper Southern Lady. She took the requisite ballet lessons from Miss Mitwidie’s Dance Studio. She learned formal dining etiquette, played the piano, sewed buttons on dresses, and planted herbs. Those skills were the ones her mother, Clayton, had learned in her youth, and she was simply passing the torch on to her daughter, molding Rhea into the only type of girl she knew how to make.

“People always followed in their parents’ footsteps, and I always thought I would be like my mother—be a southern belle and stay home and cook and raise babies,” Rhea said. But her father, Edward, had other ideas. An attorney, Edward wanted Rhea to have more than what her mother and grandmother had growing up. That meant exposing Rhea to a more diverse range of experiences. One night in October 1957, Edward pulled Rhea outside and pointed her gaze toward the darkened sky. There she watched a tiny blip of light zoom through the darkness. The tiny dot was Sputnik, an aluminum-based satellite the size of a beach ball that was beeping as it circled the Earth. The Soviet Union had just launched the spacecraft a day or two prior on October 4, putting the first human-made object into orbit. Fear had coursed through the American public over the Soviet Union’s newfound space dominance.

But others also realized that it was a watershed moment for everyone, not just the Soviets. “You are watching the beginning of a new era,” Edward said. “It’s called the Space Age.” Although she was a month shy of turning ten years old at the time, Rhea’s still-forming mind could grasp that a new world was on its way. However, she didn’t quite realize at the time just how big a role space would play in her life.

The launch of Sputnik would ultimately put Rhea on a different path than the prim and proper one her mother had envisioned for her. One of America’s knee-jerk responses to Sputnik was to increase the level of science education in grade schools, an attempt to train the next generation of youngsters to become a new breed of brainiac who could keep the US competitive in the unfolding Space Race. Soon, Rhea fell in love with her science courses—particularly life sciences. But she still stuck to the recipe. She would eagerly dig through the innards of a dissected rat during the day while performing stunts with the cheerleading squad after school.

For undergrad, she journeyed to the University of California at Berkeley, a place she’d chosen for its life sciences program. But the school felt as if it existed on another planet, let alone another state. She started as a freshman in 1965, and arrived at a campus bursting with political activism. The year prior to her arrival the Free Speech Movement had erupted when students flooded the university, protesting the arrest of a fellow student for handing out leaflets on campus. An era of political protests followed—with some students decrying the atrocities of the Vietnam War and others championing the civil rights movement and the Black Panthers. The heated rhetoric and liberal tilt were a shock for a seventeen-year-old from a conservative Tennessee town that had a third of UC Berkeley’s population.

Rhea’s GPA struggled that first year. Then the summer after her freshman year, she got a taste of a surgeon’s life. Her father, Edward, had been on the board of directors of a small hospital in her hometown, and he arranged for Rhea to get a summer job there. Originally, she’d planned to work in the ICU of the hospital’s new Coronary Care Unit, but its opening had been delayed. Instead, the doctors sent her to work in surgery. Rhea was hooked from the start. She’d leveled up from peering into the open cavities of dissected frogs and rodents; now, she was staring inside the stomachs of actual patients.

That job guided her when she entered medical school at the University of Tennessee in 1970, since, by then, she knew she wanted to follow the path of a surgeon. It was a path that almost didn’t happen. In college she’d almost gotten married, and even had a wedding date set. “Came close to the time of the wedding, and I said, ‘Not going to work,’?” Rhea would later say. “He wants me to iron his shirts and stay at home and not go to work. So I backed out of the wedding.” In hindsight, it turned out to be the right decision.

In her first year, she’d been one of just six women in a class of more than one hundred. As she worked her way through school, her internship, and her residency, she got used to being surrounded by men. And while the idea of becoming a doctor was top of mind, she also had a hidden motive for going to medical school. Secretly, she wondered if it might lead to a future in space. In watching Sputnik careen across the sky, a seed had been planted. She figured that one day there’d be a future with space stations orbiting Earth, staffed with doctors. Perhaps she could be one of those doctors to live in space.

It had been the most minuscule thought, but it had stayed with her for years. And it was on her mind that early morning in the doctors’ lounge after the gunshot wound surgery. Smelling of body odor and other human fluids, Rhea contemplated if this was the life she really wanted. At that moment a neurosurgery resident named Russ waltzed into the lounge and sat next to her. He seemed to be having the same existential crisis as Rhea, and the two friends commiserated over their exhaustion. He then posed a question that many ask when their current situation seems dim.

“What would you do if you weren’t doing this?”

Rhea paused for a moment and then answered honestly. “I’d be an astronaut.” It was perhaps the first time she’d ever said anything like that.

To anyone else it may have been a strange response, but Russ had a surprising reply. “I used to work for NASA,” he said. He explained his old job, though Rhea didn’t quite fully understand what he did. But Russ noted that he still kept in touch with his former coworkers in the space program. The conversation petered out from there, and the two residents eventually got up from their seats to finish their rounds.

A couple weeks later, Rhea was back at the John, going through her typical day of opening human bodies and stitching them shut. At one point she saw Russ, who was rushing to his next surgery. As the two passed each other, he suddenly remembered what Rhea had told him in the doctors’ lounge and stopped her. “Hey, some friends of mine say they’re taking applicants for the Space Shuttle program,” he said. “I hear they have an affirmative action program!” He then hurried off without giving any more information.

Rhea stood there stunned, a million questions running through her head.

IT WAS AUGUST 1963 and Shannon Wells could almost taste freedom. In just two weeks, she was about to graduate from the University of Oklahoma with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. No more tests, no more papers. It was time to start thinking about actual employment. But as graduation day quickly approached, Shannon realized she didn’t know anyone in her life who’d successfully snagged a job related to her field, and she had no idea how to get started. She figured one of her teachers might help her.

“I’m graduating in two weeks,” Shannon recalled saying to her inorganic chemistry professor during one of her last classes. “How do I go about getting a job in chemistry?”

The professor seemed stunned. “What?” he asked, incredulous. “You’re going to get a job?”

“Yes!” Shannon replied. “That’s why I majored in chemistry.”

Shaking his head, her teacher made his opinion clear: “There’s absolutely no one who will hire you.” He didn’t say it outright, but Shannon understood what he meant. It was because she was a woman.

Shannon left the meeting shaken. But the hard truth was that her teacher had been right.

Sadly, dealing with these kinds of remarks had been a hallmark of Shannon’s life up until this point. Shannon had always thirsted for adventure, even before her arms and legs had mustered the strength to crawl, but the world seemed intent on keeping her in her “place.”

Shannon Wells—later to become Shannon Lucid—hadn’t been born in Oklahoma but, rather, in Shanghai, China, where her parents were two expats who’d met and fallen in love there. Her mother, Myrtle, had mostly grown up in China as the daughter of a missionary doctor who’d moved his family across the world to treat patients with leprosy and tuberculosis. The adult Myrtle happened to attend a Christmas party in Shanghai in 1940. There she met a Baptist missionary named Joseph Oscar Wells, who’d just come to the country out of college.

That night, Joseph, who went by Oscar, made a bold prediction to Myrtle. “We’re going to end up getting married,” he told her. Oscar officially proposed on Valentine’s Day, and they were married on June 1.

Less than two years into the marriage, Shannon was born on January 14, 1943. And just six weeks after she’d entered the world, she and her family were captured by the Japanese army and interned in a concentration camp at Shanghai’s Chapei Civilian Assembly Center during World War II. That time is lost to Shannon, whose mind was too new to retain memories from the internment. The family wound up living in the camp for roughly a year, and then eventually boarded a Japanese vessel that took them to India—the first leg of a trip to return them to the United States. Myrtle only had one diaper for Shannon the entire voyage.

When they reached India, the family boarded the MS Gripsholm, a large Swedish ocean liner in service to the US State Department that was used for years to conduct prisoner exchanges. The boat carried a mix of American, Canadian, Japanese, and German POWs, all headed to various exchange points throughout the world. While on the vessel, the Wells family sailed around the globe twice as they made their way back to the US. They stopped at a port in Johannesburg, South Africa, along the way, where Shannon received her first pair of shoes. As a very young child, Shannon knew life as constant motion. She figured that was just how most families lived.

The Wells family eventually arrived in New York Harbor and waited out the remainder of the war in the United States, but they returned to China once the fighting stopped, when Shannon’s inquisitive mind was newly stimulated.

It would ultimately be travel by air that would capture Shannon’s fascination. When she was five, her family briefly moved to the mountainous village of Kuling, to escape the oppressive summer heat of Shanghai that might have proven fatal to her pneumonia-prone sister. For the first leg of the trip west, they piled into a DC-3 leftover from the war. Shannon’s mother, brother, and sister all struggled to hold back their lunch in the turbulent air, but not Shannon. She peered out the window in awe, fascinated by the wispy clouds swirling around the mountain peaks. As the plane came in for landing on a tiny gravel runway, she spotted a little spec on the ground. The speck grew bigger, and Shannon realized it was a person, and that soon they’d be on the ground standing next to him.

“I saw this figure, this person standing down there with a red scarf around his neck and I thought it was the most amazing thing in the world—that a human being, the pilot, will be able to get the airplane down there,” Shannon recalled. At that moment, Shannon made an easy decision: she was going to learn how to fly planes herself someday.

The Wells’s second stay in China didn’t last very long. While Shannon was in kindergarten, the Communist Revolution occurred and the family was expelled from the country. They settled for good in Bethany, Oklahoma, but Shannon couldn’t quite accept their sedentary lifestyle. One day in the family’s kitchen, she asked her mother, “Why don’t we ever go anywhere? Why are we just sitting here?”

“But it’s wonderful!” Myrtle replied, much happier with her new stationary life.

“No, it’s not! I need to get moving!” said Shannon.

As it turned out, she’d find a new way to travel without ever having to leave the house. In grade school, she picked up her first science fiction novel and escaped into the distant depths of the cosmos. She was hooked. She consumed tale after tale of spacefaring civilizations and astronaut heroes exploring the universe, picking up a new book as soon as the old one was finished. Not long after her love of sci-fi began, she learned of Robert Goddard, one of the earliest pioneers of rocketry (and the namesake of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland), who’d conducted test flights of prototype rockets in New Mexico. Soon, Shannon was building rockets of her own—or, more accurately, models of them—and she’d train in the attic inside her own cardboard spaceship, one she was determined to fly all the way to Mars.

It became an all-consuming passion. When her uncle visited from Michigan one day, she regaled him for hours on the topic of rockets and why the US should have a space program. “Don’t you talk about anything else?” he asked.

Shannon never let go of her love of space exploration. Desperate to go into space herself, she read a newspaper article at the age of twelve that suggested the Soviet Union would be sending humans to space soon. She’d found a way off the planet! she thought. Delighted, she cut the article from its main page and showed it to her mother, coming to an important conclusion.

“I’m going to have to become a Communist to go to space!” Shannon observed.

The declaration didn’t go over well in the conservative Wells household.

It wouldn’t be long before Shannon got her wish of a US-led space program. One day, she saw seven men grace the cover of Life. Within the magazine’s pages, they were hailed as heroes and trailblazers. The men were part of NASA’s pioneering Project Mercury, a program that would pack the first Americans into rockets to screech beyond Earth’s atmosphere and travel into the void of space. The group would be dubbed the Mercury Seven, and they’d go on to achieve many of the United States’ biggest milestones in human spaceflight.

When Shannon saw the cover, she instantly noticed a trend. There was a John, an Alan, a Gus. Only white men had been picked to be part of this elite spacefaring group. Her heart sank. I’m totally excluded.

Not content to accept these unfair circumstances, she penned a letter to the magazine, asking its editors to explain why America was only sending men into space. Are all Americans included? she wanted to know. Surprisingly, she received a one-sentence reply from some unknown editor.

“Someday, maybe females can go into space too,” Shannon recalled the letter saying.

“Someday” seemed to be taking a while, though, both in the field of space exploration and in various scientific disciplines on Earth. When Shannon graduated college, she couldn’t find any chemistry-oriented employers to give her a chance, just as her professor had predicted. The first job she could manage to get right out of school was working the midnight shift in a retirement home—a far cry from the field of chemistry. “You just had to take up the crumbs that were left, that no one else wanted to do,” Shannon would later say.

Eventually, an opportunity opened up. A lab employee at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation walked out on the job suddenly, and the institute was desperate to fill the position. Conveniently, there was Shannon, ready and willing to fill in. The nonprofit hired her as a technician in the cancer research program, and Shannon got her first taste of real lab work for a couple of years. While she loved working there, she noted that “discrimination was alive and real,” and there was essentially no way she could advance.

When a key grant fell through and Shannon was told her job would be ending in two weeks, she had to act fast. She had payments due on a very important vehicle she owned: a Piper Clipper airplane. Once she’d graduated high school, Shannon had followed through on the pledge she’d made back in China, when she saw that tiny man in the bright red scarf. She took flying lessons, got her pilot’s license, and eventually saved enough money to buy herself the tiny Clipper. She and her father would fly in it together to church meetings. But to keep the plane in the air, Shannon had to find another source of income—quick.

She sent out résumé after résumé, yearning for a response. Since Shannon wasn’t a very common name back then, she’d sometimes get letters addressed to Mr. Shannon Wells. She soon learned those would be the nicer responses she’d get. One time a company asked her to send a picture of herself. When she did, she got a letter by express mail telling her explicitly that the company had absolutely no jobs available. None.

“People weren’t hiring women back in those days,” Shannon recalled. “And when I tried to get on with the federal government and their science labs, they wouldn’t even look at a female.”

Finally, Shannon went to an employment agency in Oklahoma City and proclaimed that she was desperate. Did they have anything that’d be right for her? The agency told her that a position had recently opened at Kerr-McGee, an oil company based in the city. An employee at the company was about to leave for six months to undergo training with the National Guard, and Kerr-McGee needed someone to fill in while he was away. It wouldn’t be a permanent position, though. The man’s job would be waiting for him when he got back. But Shannon could take his spot in the meantime.

Shannon happily accepted, even though she recognized an unfair situation. “I was coming in as a college graduate with some master’s courses working in a job for somebody that I think was a college dropout.”

Still, she was grateful to be employed and working in a field that actually put her chemistry skills to use. While filling in at the company, she worked under multiple men, one of whom was named Michael Lucid. He’d originally thought the company was wrong to hire Shannon for just six months, since she was so overqualified for the position. But since he wasn’t the boss, his opinion had been overruled. He didn’t say much to Shannon while they worked together.

Six months sped by, and just before Shannon’s employment period was up, one of her bosses approached her and asked what her plans were. At the time, Shannon had been sucked back into another frantic job search, a pastime that was becoming routine, and she told him that she was in serious need of employment. He said that Kerr-McGee was open to hiring her full-time and quoted a measly starting salary. Shannon responded that she knew her coworker David, who’d been working in the same lab, was making much more than that, though he had less education.

Her boss just stared at her. “Shannon, you’re a female. There’s no way we’re going to pay you the same that we’re paying anybody else.” She didn’t have much of a choice. A quick look at the calendar showed she’d be out of a job in two weeks. She agreed, once again, to another unfair employment situation.

After coming on in a more permanent position, Shannon got an unexpected call in February 1967. On the line was Mike, her former boss, and he wanted to know if she was interested in going to the boat show with him that weekend. The request came as a bit of a shock. Shannon had absolutely no idea that he was ever interested in her. She also had plans to take her plane out that same weekend. But bad weather prevented her from flying, so she went to the boat show with Mike instead.

The pair started dating, and it didn’t take long before Mike suggested they get married. When he first brought it up, Shannon told him there was no way that was going to happen. “I plan to be a person—not someone’s wife,” she said. Shannon had been burned too many times—throughout her childhood and her career—and she knew that married women were expected to stay home and do… something. “I never could figure out what people did at home,” said Shannon.

Mike, who’d grown up in the same restrictive decade of the 1950s, told Shannon that there was absolutely no reason she couldn’t work as much as she wanted while she was married. He’d fallen for the woman he’d met at Kerr-McGee, and he didn’t want to marry a completely different person.

Shannon then confessed to Mike a secret desire, one she’d harbored since she was a little girl. She wanted to work for NASA someday—as an astronaut. What did he think about that?

The proclamation didn’t sway him. “Absolutely, no problem.”

Michael and Shannon got married at her home in December 1967. And almost instantly the new family started to grow. They conceived their first daughter on their honeymoon in Hawaii, whom they would name Kawai Dawn, after the island they’d visited. The newlyweds lived in a state of pure bliss those first few weeks post-nuptials.

Then Shannon informed Kerr-McGee of her pregnancy, and her bosses immediately fired her.

The joys of marriage were quickly overshadowed by the familiar sting of unemployment—at least for Shannon. Kerr-McGee didn’t see any reason to fire Mike. He continued to go to work to make money for the family, and for weeks Shannon would stand at the door crying as he left each morning. Finally, Mike declared that this routine had to end. “We can’t live like this,” he told her. So he made a suggestion: Why didn’t Shannon go to graduate school and get an advanced degree? In such an unfair world as the one they inhabited in the 1960s, Shannon clearly needed to accumulate as many credentials as she could to find long-term employment.

So Shannon returned to the University of Oklahoma to get both her master’s and PhD in biochemistry. During that time, she and Mike had their second daughter. When Shandara was born, Shannon was back at school less than a week later to take her finals. “I couldn’t put off the test,” Shannon explained.

It took four years for Shannon to achieve the pinnacle of academic rank, and even after she’d graduated with her PhD, finding employment still turned out to be a struggle. She suffered again through months of job searches, sending out round after round of government applications. But she ultimately landed at a familiar place. The Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation took her on again in 1974, this time as a research assistant to study how various chemicals caused cancer in cells. She stayed for the next few years, finally content in a full-time position.

Then one day in July 1976 Shannon was working in the lab, reading the foundation’s science magazine, when she spotted a short article toward the back. The blurb mentioned that NASA was recruiting a new round of astronauts for the agency’s new Space Shuttle. And this time, the agency wanted women to apply.

ANNA LEE (SOON to become Anna Fisher) slumped down in a chair at Harbor General Hospital in Los Angeles, completely exhausted. She was in the midst of another twelve-hour day at her surgical internship, a gauntlet that had become pretty standard for her after graduating from UCLA’s medical school. The entire last year had been like this, filled with back-to-back shifts on her feet and calls to perform last-minute surgeries at any wild hour of the night. She knew these were the dues she had to pay to become a surgical resident, but she’d started to wonder if this was really the kind of life she wanted.

As she took a second to relax, she heard a familiar voice over the hospital’s PA system. It was that of her fiancé Bill Fisher. He was paging Anna to call him back. I wonder what this is about? she thought.

Anna wrenched herself from her chair and made her way to a nearby phone. She looked around Harbor General as she walked, the place she’d spent almost all her time this past year. In truth, her relationship with the hospital went back even further. Anna had volunteered at Harbor General while she was at San Pedro High School in the late 1960s, along with her friend Karen Hayes. The two had been candy stripers at the hospital. The name was a nod to the pink-and-white pinafore uniforms that women wore during their volunteer work. It had been a particularly daunting introduction to the world of medicine, as the hospital’s wards were filled with severely ill cancer patients, and their pain weighed on Anna. So she and Karen opted to sequester themselves by developing X-ray photographs in the hospital’s darkroom, a pretty important gig for two high school students.

It was during their volunteer work that Anna had admitted something huge to Karen. One day the two friends stood next to each other in the dark, flipping film and plunging the photographs into their processing chemicals. Perhaps it was the absence of light that made Anna feel comfortable sharing her deepest desire. The darkness obscured her friend’s face, masking whatever facial expression she might have in response. But in that moment she confessed to Karen something she’d never told anyone. “I’d really like to be an astronaut someday,” Anna admitted, as the two talked about their futures beyond high school.

Karen was shocked, since her friend had never betrayed a hint of that aspiration. But the truth was that Anna had been thinking about it since junior high. Specifically, she’d been thinking about it since May 5, 1961.

That day, a man by the name of Alan Shepard donned a silvery space suit and a white helmet in Cape Canaveral, Florida. Just before four in the morning, he boarded a white van that dropped him off in front of a large black-and-white rocket, hissing and venting gas while it waited on a red metallic launchpad. Emblazoned on the side of the vehicle were the words UNITED STATES in bright red letters. With a portable air-conditioning unit in his right hand, Alan stepped out of the van and peered up at the rocket, a Redstone, one last time.

He then climbed into a capsule perched on top of the missile and, hours later, took off into the sky. The rocket propelled his Mercury capsule, dubbed Freedom 7, to a height of 116 statute miles above Earth’s surface, before it dropped back down and splashed underneath a parachute in the Atlantic Ocean. From takeoff to splashdown, the entire flight took just fifteen minutes. But in that short interval, Al became the first American to reach space. He hadn’t been the first man ever, though. That title went to Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet pilot who’d successfully orbited Earth less than a month earlier.

Anna, nearly twelve years old at the time, listened to the entirety of the flight on a transistor radio outside her school at Fort Campbell, an army base straddling the Kentucky-Tennessee border. She and her classmates sat on their playground’s dewy grass, all packed in tight around the radio, hoping to puzzle out the scratchy audio from the announcers. Anna had been worried she might miss the launch entirely that morning. The flight was originally supposed to take off at 7:20 a.m. EST, when she had to get ready for school. But thick clouds above the launch site pushed the launch back a couple of hours, putting liftoff right in the middle of her first-period PE class. Luckily for Anna, her teacher paused the day’s fitness tests so that the kids could experience history. (It wasn’t so lucky for Alan Shepard, who wound up relieving himself in his space suit after four hours of waiting for the launch to get off the ground.)

Those fifteen minutes of spaceflight forever imprinted themselves on Anna’s heart. “As he launched and I listened to him, I decided at that moment that, if I ever had a chance, that’s what I wanted to do,” she said. For her, the job was the perfect combination of everything she enjoyed: it involved science, it was challenging, and it involved exploring the unknown.

It was a moment of clarity in a life defined until that point by motion. Her father, Riley Tingle, was a sergeant in the US Army and would uproot the family each time he got reassigned to a new military base. Such a life had its benefits. For one, Anna wouldn’t have been born if her father hadn’t traveled the globe. His career led him to Berlin after World War II, where he met Elfriede, a German-born woman working for the US military—a job she secured thanks to her extensive knowledge of English. They married in April 1949 and came back to the United States together, where they had Anna. As soon as she entered the world, she found herself in a new hometown every couple of years. A shy little girl who enjoyed doing her math homework each night, she struggled to make friends and to shape her own identity.

It wasn’t until that moment outside her school in Fort Campbell that Anna had true resolve on the kind of path she wanted to take—though she immediately thought her dream would never be possible for her. She, too, had noticed that only men had been selected to be astronauts thus far. Plus, all the astronauts had to have jet piloting experience, something you could only get by joining the US military. And women were prohibited from flying jets for the armed forces.

When Anna turned thirteen, she finally got a reprieve from the transient lifestyle when her family settled in San Pedro, California, a town populated by immigrant families from across the globe. Anna would later be grateful that she spent the remainder of her childhood in one place. The junior high school she attended in San Pedro was her thirteenth school, which meant she’d averaged about one new school every year of her life. She welcomed a break from learning the names of a whole new crop of classmates every couple of semesters.

By the time Anna had moved past her candy striper phase and gone off to college in 1967, her dream of flying to space had been pushed deep into the back of her consciousness. And that meant thinking practically about her future. She was accepted at UCLA, the one school she applied to, having done so well on her SATs that the school awarded her a merit scholarship during a ceremony in front of the entire student body. She was the first in her family to go to college, and as such, a bit of an anomaly for women in those years. Her teachers didn’t exactly encourage women to seek college degrees, and most women in Anna’s school didn’t aspire to more schoolwork or full-time employment. They’d been told most of their lives they wouldn’t need such things when they grew older.

Anna initially chose math as her route, but she started to wonder what she would actually do with a degree in advanced mathematics. She ultimately decided she didn’t want to be a math professor or theoretical mathematician, which meant she should probably consider another path. In the meantime, she’d taken a few chemistry classes, which had really intrigued her. So she made the leap to a chemistry degree, figuring that she could do more with a science education.

Her time at UCLA had been illuminating and intense. She’d had a brief whirlwind romance, both marrying and then later separating from a man who turned out not to be the right partner for her. And as her undergraduate years came to an end, Anna decided she’d apply to medical school at UCLA, instead of doing research with her chemistry degree. While she loved the idea of a career as a doctor, there was a hidden motive for this move. Still dreaming of going to space one day, she figured that eventually there’d be space stations orbiting the Earth—and those stations would need doctors. Just like Rhea had imagined, Anna thought perhaps she could be the one to live at those stations, attending to the sick astronauts. It was a unique gamble that she kept to herself during the admissions interview.

Even though she kept her astronaut ambitions to herself, UCLA rejected her application initially, putting her on the wait list. For Anna, it was a blow, but she decided to make the most of that time. She pursued her master’s in chemistry while working as a teaching assistant. At the time, it seemed like a failure to wait, but the degree would come in handy in the years to come.

When she did get into medical school, she opted to attend Harbor General for her internship, a place that was familiar to her. And it was there that she met Bill, another surgical intern who was a year ahead of her. They met in the hospital’s cafeteria when Anna overheard a group laughing at Bill, who was loudly telling a few blush-inducing jokes. He looked more like a movie doctor than a real one, with a chiseled jawline and a full gleaming smile. The two also had quite a few things in common. Of course, they shared a passion for medicine, but it also turned out that both harbored a deep desire to become an astronaut, something they learned on their first date. The two would talk all the time about how if the opportunity ever came up, they’d jump at the chance to apply to NASA. The couple quickly became smitten with each other, and Bill proposed less than a year after they met.

Anna eventually found a phone to call her fiancé in Harbor General that day after getting his page. Bill’s exuberance seemed to leap out of the phone’s speaker. He explained that he’d just had lunch with a mutual friend, Dr. Mark Mecikalski, who disclosed a major piece of information. An avid fan of NASA, Mark had learned that the agency was about to recruit a new round of astronauts, with women encouraged to apply. And since Anna and Bill were always talking about working for NASA one day, he figured they should know about the selection.

The news filled her with newfound energy. This was the moment Anna had been waiting for ever since she was a little girl, and here she was with the right credentials to give it a shot.

There was only one problem, Bill told her.

“We have three weeks to apply before the deadline,” he said.

The Six: The Extraordinary Story of the Grit and Daring of America's First Women Astronauts

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: Scribner

- ISBN-10: 1982172819

- ISBN-13: 9781982172817