Excerpt

Excerpt

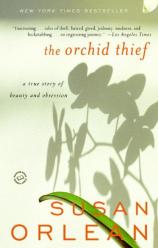

The Orchid Thief

The Millionaire's Hothouse

John Laroche is a tall guy, skinny as a stick, pale-eyed, slouch-shouldered, and sharply handsome, in spite of the fact that he is missing all his front teeth. He has the posture of al dente spaghetti and the nervous intensity of someone who plays a lot of video games. Laroche is thirty-six years old. Until recently he was employed by the Seminole Tribe of Florida, setting up a plant nursery and an orchid-propagation laboratory on the tribe's reservation in Hollywood, Florida.

Laroche strikes many people as eccentric. The Seminoles, for instance, have two nicknames for him: Troublemaker and Crazy White Man. Once, when Laroche was telling me about his childhood, he remarked, "Boy, I sure was a weird little kid." For as long as he can remember he has been exceptionally passionate and driven. When he was about nine or ten, his parents said he could pick out a pet. He decided to get a little turtle. Then he asked for ten more little turtles. Then he decided he wanted to breed the turtles, and then he started selling turtles to other kids, and then he could think of nothing but turtles and then decided that his life wasn't worth living unless he could collect one of every single turtle species known to mankind, including one of those sofa-sized tortoises from the Galapagos. Then, out of the blue, he fell out of love with turtles and fell madly in love with Ice Age fossils. He collected them, sold them, declared that he lived for them, then abandoned them for something else--lapidary I think--then he abandoned lapidary and became obsessed with collecting and resilvering old mirrors. Laroche's passions arrived unannounced and ended explosively, like car bombs. When I first met him he lusted only for orchids, especially the wild orchids growing in Florida's Fakahatchee Strand. I spent most of the next two years hanging around with him, and at the end of those two years he had gotten rid of every single orchid he owned and swore that he would never own another orchid for as long as he lived. He is usually true to his word. Years ago, between his Ice Age fossils and his old mirrors, he went through a tropical-fish phase. At its peak, he had more than sixty fish tanks in his house and went skin-diving regularly to collect fish. Then the end came. He didn't gradually lose interest: he renounced fish and vowed he would never again collect them and, for that matter, he would never set foot in the ocean again. That was seventeen years ago. He has lived his whole life only a couple of feet west of the Atlantic, but he has not dipped a toe in it since then.

Laroche tends to sound like a Mr. Encyclopedia, but he did not have a rigorous formal education. He went to public school in North Miami; other than that, he is self-taught. Once in a while he gets wistful about the life he thinks he would have led if he had applied himself more conventionally. He believes he would have probably become a brain surgeon and that he would have made major brain-research breakthroughs and become rich and famous. Instead, he lives in a frayed Florida bungalow with his father and has always scratched out a living in unaverage ways. One of his greatest assets is optimism--that is, he sees a profitable outcome in practically every life situation, including disastrous ones. Years ago he spilled toxic pesticide into a cut on his hand and suffered permanent heart and liver damage from it. In his opinion, it was all for the best because he was able to sell an article about the experience ("Would You Die for Your Plants?") to a gardening journal. When I first met him, he was working on a guide to growing plants at home. He told me he was going to advertise it in High Times, the marijuana magazine. He said the ad wouldn't mention that marijuana plants grown according to his guide would never mature and therefore never be psychoactive. The guide was one of his all-time favorite projects. The way he saw it, he was going to make lots of money on it (always excellent) plus he would be encouraging kids to grow plants (very righteous) plus the missing information in the guide would keep these kids from getting stoned because the plants they would grow would be impotent (incalculably noble). This last fact was the aspect of the project he was proudest of, because he believed that once kids who bought the guide realized they'd wasted their money trying to do something illegal--namely, grow and smoke pot--they would also realize, thanks to John Laroche, that crime doesn't pay. Schemes like these, folding virtue and criminality around profit, are Laroche's specialty. Just when you have finally concluded that he is a run-of-the-mill crook, he unveils an ulterior and somewhat principled but always lucrative reason for his crookedness. He likes to describe himself as a shrewd bastard. He loves doing things the hard way, especially if it means that he gets to do what he wants to do but also gets to leave everyone else wondering how he managed to get away with it. He is quite an unusual person. He is also the most moral amoral person I've ever known.

I met John Laroche for the first time a few years ago, at the Collier County Courthouse in Naples, Florida. I was in Florida at the time because I had read a newspaper article reporting that a white man--Laroche--and three Seminole men had been arrested with rare orchids they had stolen out of a Florida swamp called the Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve, and I wanted to know more about the incident. The newspaper story was short but alluring. It described the Fakahatchee as a wild swamp near Naples filled with exceptional plants and trees, including some that don't grow anywhere else in the United States and some that grow nowhere else in the world. All wild orchids are now considered endangered, and it is illegal to take them out of the woods anywhere, and particularly out of a state property like the Fakahatchee. According to the newspaper, Laroche was the ringleader of the poachers. He provided the arresting officers with the proper botanical varietal names for all the stolen plants and explained that the plants were bound for a laboratory where they were going to be cloned by the millions and then sold to orchid collectors around the world.

I read lots of local newspapers and particularly the shortest articles in them, and most particularly any articles that are full of words in combinations that are arresting. In the case of the orchid story I was interested to see the words "swamp" and "orchids" and "Seminoles" and "cloning" and "criminal" together in one short piece. Sometimes this kind of story turns out to be something more, some glimpse of life that expands like those Japanese paper balls you drop in water and then after a moment they bloom into flowers, and the flower is so marvelous that you can't believe there was a time when all you saw in front of you was a paper ball and a glass of water. The judge in the Seminole orchid case had scheduled a hearing a few weeks after I read the article, so I arranged to go down to Naples to see if this ball of paper might bloom.

It was the dead center of winter when I left New York; in Naples it was warm and gummy, and from my plane I could see thick thunderclouds trolling along the edge of the sky. I checked into a big hotel on the beach, and that evening I stood on my balcony and watched the storm explode over the water. The hearing was the next morning at nine. As I pulled out of the hotel garage the parking attendant warned me to drive carefully. "See, in Naples you got to be careful," he said, leaning in my window. He smelled like daiquiris. It was probably suntan lotion. "When it rains here," he added, "cars start to fly." There are more golf courses per person in Naples than anywhere else in the world, and in spite of the hot, angry weather everyone around the hotel was dressed to play, their cleated shoes tapping out a clickety-clickety-clickety tattoo on the sidewalks.

The courthouse was a few miles south of town in a fresh-looking building made of bleached stone pocked with fossilized seashells. When I arrived, there were a few people inside, nobody talking to anybody, no sounds except for the creaking of the wooden benches and the sound of some guy in the front row gunning his throat. After a moment I recognized Laroche from the newspaper picture I'd seen. He was not especially dressed up for court. He was wearing wraparound Mylar sunglasses, a polyblend shirt printed with some sort of scenic design, a Miami Hurricanes baseball cap, and worn-out grayish trousers that sagged around his rear. He looked as if he wanted a cigarette. He was starting to stand up when the judge came in and settled in her chair; he sat down and looked cross. The prosecutor then rose and read the state's charges--that on December 21, 1994, Laroche and his three Seminole assistants had illegally removed more than two hundred rare orchid and bromeliad plants from the Fakahatchee and were apprehended leaving the swamp in possession of four cotton pillowcases full of flowers. They were accused of criminal possession of endangered species and of illegally removing plant life from state property, both of which are punishable by jail time and fines.

The judge listened with a blank expression, and when the prosecutor finished she called Laroche to testify. He made a racket getting up from his seat and then sauntered to the center of the courtroom with his head cocked toward the judge and his thumbs hooked in his belt loops. The judge squinted at him and told him to state his name and address and to describe his expertise with plants. Laroche jiggled his foot and shrugged. "Well, Your Honor," he said, "I'm a horticultural consultant. I've been a professional horticulturist for approximately twelve years and I've owned a plant nursery with a number of plants of great commercial and ethnobiological value. I have very extensive experience with orchids and with the asexual micropropagation of orchids under aseptic cultures." He paused for a moment and grinned. Then he glanced around the room and added, "Frankly, Your Honor, I'm probably the smartest person I know."

I had never heard of the Fakahatchee Strand or its wild orchids until I heard about John Laroche, in spite of the fact that I'd been to Florida millions of times. I grew up in Ohio, and for years my family went to Miami Beach every winter vacation, staying at hotels that had fishing nets and crusty glass floats decorating the lobbies and dwarf cabbage palms standing in for Christmas trees. Even then I was of a mixed mind about Florida. I loved walking past the Art Deco hotels on Ocean Drive and Collins Road, loved the huge delis, loved my first flush of sunburn, but dreaded jellyfish and hated how my hair looked in the humidity. Heat unsettles me, and the Florida landscape of warm wideness is as alien to me as Mars. I do not consider myself a Florida person. But there is something about Florida more seductive and inescapable than almost anywhere else I've ever been. It can look brand-new and man-made, but as soon as you see a place like the Everglades or the Big Cypress Swamp or the Loxahatchee you realize that Florida is also the last of the American frontier. The wild part of Florida is really wild. The tame part is really tame. Both, though, are always in flux: The developed places are just little clearings in the jungle, but since jungle is unstoppably fertile, it tries to reclaim a piece of developed Florida every day. At the same time the wilderness disappears before your eyes: fifty acres of Everglades dry up each day, new houses sprout on sand dunes, every year a welt of new highways rises. Nothing seems hard or permanent; everything is always changing or washing away. Transition and mutation merge into each other, a fusion of wetness and dryness, unruliness and orderliness, nature and artifice. Strong singular qualities are engaging, but hybrids like Florida are more compelling because they are exceptional and strange. Once near Miami I saw a man fishing in a pond beside the parking lot of a Burger King right next to the highway. The pond was perfectly round with trim edges, so I knew it had to be phony, not a natural pond at all but just the "borrow pit" that had been left when dirt was "borrowed" to build the roadbed of the highway. After the road was completed and the Burger King opened, water must have rained in or seeped into the borrow pit, and then somehow fish got in--maybe they were dropped in by birds or wiggled in through underground fissures--and pretty soon the borrow pit had turned into a half-real pond. The wilderness had almost taken it back. That's the way Florida strikes me, always fomenting change, its natural landscapes just moments away from being drained and developed, its most manicured places only an instant away from collapsing back into jungle. A few years ago I was linked to Florida again; this time my parents bought a condominium in West Palm Beach so they could spend some time there in the winter. There is a beautiful, spruced-up golf course attached to their building, with grass as green and flat as a bathmat, hedges precision-shaped and burnished, the whole thing as civilized as a tuxedo. Even so, some alligators have recently moved into the water traps on the course, and signs are posted in the locker room saying ladies! beware of the gators on the greens!

The state of Florida does incite people. It gives them big ideas. They don't exactly drift here: They come on purpose--maybe to start a new life, because Florida seems like a fresh start, or to reward themselves for having had a hardworking life, because Florida seems plush and bountiful, or because they have some new notions and plans, and Florida seems like the kind of place where you can try anything, the kind of place that for centuries has made entrepreneurs' mouths water. It is moldable, reinventable. It has been added to, subtracted from, drained, ditched, paved, dredged, irrigated, cultivated, wrested from the wild, restored to the wild, flooded, platted, set on fire. Things are always being taken out of Florida or smuggled in. The flow in and out is so constant that exactly what the state consists of is different from day to day. It is a collision of things you would never expect to find together in one place--condominiums and panthers and raw woods and hypermarkets and Monkey Jungles and strip malls and superhighways and groves of carnivorous plants and theme parks and royal palms and hibiscus trees and those hot swamps with acres and acres that no one has ever even seen--all toasting together under the same sunny vault of Florida sky. Even the orchids of Florida are here in extremes. The woods are filled with more native species of orchids than anywhere else in the country, but also there are scores of man-made jungles, the hothouses of Florida, full of astonishing flowers that have been created in labs, grown in test tubes, and artificially multiplied to infinity. Sometimes I think I've figured out some order in the universe, but then I find myself in Florida, swamped by incongruity and paradox, and I have to start all over again.

By the time everyone finished testifying at the orchid-poaching hearing, the judge looked perplexed. She said this was one of her most interesting cases, by which I think she meant bizarre, and then she announced that she was rejecting the defendants' request to dismiss the charges. The trial was scheduled for February. She then ordered the defendants--Laroche, Russell Bowers, Vinson Osceola, and Randy Osceola--to refrain from entering the Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve until the case was concluded. Then she excused the orchid people and turned her attention to a mournful-looking man who was up on drug-possession charges. I caught up with Laroche right outside the courthouse door. He was smoking and standing in a huddle with three other men: the Seminole tribe's lawyer, Allan Lerner, and the vice president of the tribe's business operations, Buster Baxley, and one of the codefendants, Vinson Osceola. The other two Seminoles hadn't come to the hearing; according to Allan Lerner, one of them was sick and the other was nowhere to be found.

Buster looked as if he was in a bad mood. "I'm going right now into that swamp with a chain saw, I swear to God," he fumed. "God damn."

Laroche ground out his cigarette. "You know, I feel like I've been screwed," he said. "I've been fucking crucified."

Allan Lerner dribbled his briefcase from hand to hand. "Look, Buster," he said, "I did try to make our point. I reminded the judge that the Indians used to own the Fakahatchee, but she's obviously got something else in mind. Don't worry. We'll deal with all of this at trial." Buster scowled and started to walk away. Vinson Osceola shrugged at Allan and walked off after Buster. Allan looked around and then said good-bye to me and followed Buster and Vinson. Laroche lingered for another minute. He drummed his fingers on his chin and then said, "Those swamp rangers are a joke. None of them know anything about the plants in there. Some of them are actually dumb--I mean really dumb. They were lucky to have arrested me so I could give them the names of the plants. Otherwise I don't think they would have even known what they were. I really don't care what goes on here in court. I've been to the Fakahatchee a thousand times and I'm going to go in there a thousand more."

John Laroche grew up in North Miami, an exurb you pass through on the way from Miami to Fort Lauderdale. The Laroches lived in a semi-industrial neighborhood, but it was still pretty close to the swamps and woods. When he was a kid, Laroche and his mother would often drive over and hike through the Big Cypress and the Fakahatchee just to look for unusual things. His father never came along because he really wasn't much for the woods, and then he had broken his back doing construction work and was somewhat disabled. Laroche has no siblings, but he told me that he had a sister who died at an early age. Once, in the middle of recounting the history of the Laroches, he declared, "You know, now that I think about it, I guess we're a family of ailments and pain."

During the months I spent in Florida I met Laroche's father only briefly. I would have loved to have met his mother, who is no longer alive. Laroche described her as overweight and frumpy, and claimed that she was Jewish by birth but at different times in her life she experienced ardent attachments to different religious faiths. She was an enthusiast, a gung ho devotee. She was never the first to call an end to a hike or to chicken out when she and Laroche had to wade into sinkholes. She loved orchids. If the two of them came across an orchid in bloom, she insisted that they tag it and come back in a few months to see if the plant had formed any seeds.

When Laroche was a teenager he was fleetingly obsessed with photography. He decided he had to photograph every single species of Florida orchid in bloom, so every weekend for a while he loaded his mother with cameras and tripods and the two of them would trudge for hours through the woods. He wasn't content for very long with merely photographing the orchids--he soon decided he had to collect the orchids themselves. He stopped bringing cameras on his hikes and started bringing pillowcases and garbage bags to carry plants. In no time he gathered a sizable collection. He considered opening a nursery. He did some construction work after high school to make a living, but just like his father he fell and broke his back and had to take a disability leave. He considers breaking his back a stroke of luck because it cleared the way for him to devote himself to plants. He got married in 1983, and he and his now ex-wife did open a nursery in North Miami. They named it the Bromeliad Tree. They specialized in orchids and in bromeliads, the family of dry, spiny air plants that live in trees. Laroche concentrated on the oddest, rarest stuff. Eventually he gathered forty thousand plants in his hothouses, including some that he claims were the only specimens of their kind in cultivation. Like a lot of nursery owners, Laroche and his wife managed to just get by on their earnings, but he wasn't satisfied with just scraping by. What he wanted was to find a special plant that would somehow make him a millionaire.

A few days after the hearing, Laroche invited me to go with him to an orchid show in Miami. He picked me up in a van dappled with rust. As I opened the door and said hello, he interrupted me and said, "I want you to know that this van is a piece of shit. As soon as I hit the orchid jackpot I'm buying myself an awesome car. What are you driving?" I said I had borrowed my father's Aurora. "Awesome," Laroche said. "I think I'll get one of those." I leaned in and dug through all sorts of stuff to try to get to the passenger seat and then sat down on a few inches of the edge of it, resting my feet on a bag of potting soil that had split and spilled all over the floor. Laroche started down the road with great alacrity. I thought maybe I had suffered whiplash. Each time the van hit a pothole it squeaked and shuddered, and a hundred different trowels, screwdrivers, terra-cotta planters, Coke cans, and mystery things rolled around the floor like steel balls in a pinball machine.

I kept my eyes glued to the road because I thought it would be best if at least one of us did. "See, my whole life--that is, my whole life in the nursery world--I've been looking for a goddamn profitable plant," he said. "I had a friend in South America--he just croaked, as a matter of fact--anyway, this guy was a major commercial grower and had just endless amounts of money, and he wanted this fantastic bromeliad I had, so I told him that I'd trade it to him for just a seed or a cutting from the most valuable plant he had. I said, ŒHey, look, I don't care if the plant is gorgeous or butt-ugly.' I just wanted to see the plant that had given him his life of leisure."

"So what was it? What does a profitable plant look like?"

Laroche laughed and lit a cigarette. "He sent me this big box. In the big box was this little box, and then inside of that there was another little box, and then another box, and in the last box was a square inch of lawn grass. I thought, This guy's a real joker! Fuck this guy! I called the guy. I said, ŒHey, you son of a bitch! What the hell is this?' Well, it turns out that it was a special kind of lawn grass that was green with some tiny white stripes on the edges. That was it! He told me what an asshole I was and said I should have realized what a treasure I was holding. And, you know, he was right. When you think about it, if you could find a really nice-looking lawn grass, some cool new species, and you could produce enough seeds to market it, you would rule the world. You'd be completely set for life."

He crushed out his cigarette and steered with his knee while he lit another. I asked him what he had done with the square inch of grass. "Oh, I'm not into lawn grass," he said. "I think I gave it away."

In 1990 Laroche's life as a plant man changed. That year the World Bromeliad Conference was held in Miami. World plant conferences are attended by collectors and growers and plant fanciers from all over. At most shows growers build displays for their plants, and they compete for awards recognizing the quality of the plants and the ingeniousness of their displays. Maybe at one time show displays were uncomplicated, but nowadays the displays have to reflect the theme of the show and usually involve major construction, scores of plants, and props as substantial as mannequins, canoes, Styrofoam mountains, and actual furniture. Laroche suspected he had a knack for display building, and he was certain he had the best bromeliads in the world, so he decided to enter the competition. He designed a twelve- by twenty-five-foot exhibit using hardwood struts and tie beams, Day-Glo paint, a black light to make the Day-Glo paint glow, strings of Christmas lights arranged correctly in the shape of constellations, and dozens of a species of bromeliad that looks like little stars. The display got a lot of attention. This was a turning point for Laroche. As a result of the conference he became well known in the plant community and became even more determined to have a spectacular nursery. He began calling all over the world every day, tracking down unusual plants; his phone bills were thousands of dollars a month. Lots of money flew in and out of his hands, but he put most of it right back into his nursery. He tended to the extravagant. Once he spent five hundred dollars on an air-conditioned box for one little cool-weather fern he had gotten from a guy in the Dominican Republic. The fern died anyway, but even now Laroche says he doesn't regret the expense. He wanted the best of everything. He accumulated what he says was one of the country's largest collections of Cryptanthus, a genus of Brazilian bromeliad. He bought a spectacular six-foot-tall Anthurium veitchii with weird, corrugated leaves. He still enjoys thinking about that Anthurium. He says it was "a gorgeous, gorgeous son of a bitch."

About ten miles outside of Miami Laroche reached the part of his life story that featured orchids. He and his wife had hundreds of them at the Bromeliad Tree, and even though he had been at one time completely fascinated with the bromeliads, he found himself seduced away by the orchids. He became obsessed with breeding them. He especially loved working on hybrids--cross-pollinating different types to create new orchid hybrids. "Every time I'd make a new hybrid, it felt so cool," he said. "I felt a little like God." He often took germinating seeds and drenched them with household chemicals or cooked them for a minute in his microwave oven so that they would mutate and perhaps turn into something really interesting, some bizarre new shape or color never seen before in the orchid world. I guess I was a little shocked as he was describing the process, and when he glanced at me and caught my expression he took both hands off the wheel and waved them at me dismissively. "Oh, come on," he said.

"Mutation's great! Mutation's really fun! It's a great little hobby--you know, mutation for fun and profit. And it's cool as hell. You end up with some cool stuff and some ugly stuff and stuff no one has ever seen before and it's just great."

I asked what the point of it was. "Hey, mutation is the answer to everything," he said irritably. "Look, why do you think some people are smarter than other people? Obviously it's because they mutated when they were babies! I'm sure I was one of those people. When I was a baby I probably got exposed to something that mutated me, and now I'm incredibly smart. Mutation is great. It's the way evolution moves ahead. And I think it's good for the world to promote mutation as a hobby. You know, there are an awful lot of wasted lives out there and people with nothing to do. This is the sort of interesting stuff they should be doing."

The more orchids he collected, the more orchid collectors Laroche got to know. He was in the middle of the orchid world, but at the same time he was not really a part of it. Orchids are everywhere in Florida, wild and domesticated ones, natural and hybridized ones, growing in backyards and in shadehouses, being shipped in and out all over the world. The American Orchid Society, which was founded in 1921, is headquartered on the former estate of an avid collector in West Palm Beach, and many of the biggest and best orchid nurseries in the country--R. F. Orchids, Motes Orchids, Fennell Orchid Company, Krull-Smith Orchids--are in Florida. Some of these nurseries have been around for decades, and some Florida breeders are the third or fourth generation of their family to grow. Orchids have grown in the Florida swamps and hammocks since the swamps and hammocks have existed, and orchids have been cultivated in Florida greenhouses since the end of the 1800s. By the early 1900s, the great estates of Palm Beach and Miami had their own orchid collections and orchid keepers; orchids were considered a rich and romantic accessory, a polished little captive, a bit of wilderness under glass.

Laroche was not at all rich or romantic or polished, so he didn't fit into the Palm Beach plant lovers' world at all, but he did have a wealth of orchids. Day and night, people dropped by his nursery to talk to him about orchids and to admire his collection and to be impressed by him. They came and just hung around so they could be among his plants, or they brought him special flowers in exchange for leading them on hikes through the Fakahatchee, or they invited him over to see their collections and pumped him for advice, or they offered him truckloads of money to help them find the world's most unfindable plants. He thinks some of them called just because they were lonely and wanted to talk to someone, especially someone who shared an interest of theirs. The image of this loneliness seemed to daunt him. He stopped talking about it and then started explaining to me why he loved plants. He said he admired how adaptable and mutable they are, how they have figured out how to survive in the world. He said that plants range in size more than any other living species, and then he asked if I was familiar with the plant that has the largest bloom in the world, which lives parasitically in the roots of a tree. As the giant flower grows it slowly devours and kills the host tree. "When I had my own nursery I sometimes felt like all the people swarming around were going to eat me alive," Laroche said. "I felt like they were that gigantic parasitic plant and I was the dying host tree."

Excerpted from The Orchid Thief © Copyright 2012 by Susan Orlean. Reprinted with permission by Ballantine. All rights reserved.

The Orchid Thief

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 044900371X

- ISBN-13: 9780449003718