Excerpt

Excerpt

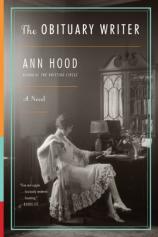

The Obituary Writer

First of all, the ones in sorrow should be urged if possible to sit in a sunny room and where there is an open fire. If they feel unequal to going to the table, a very little food should be taken to them on a tray. A cup of tea or coffee or bouillon, a little thin toast, a poached egg, milk if they like it hot, or milk toast.

—from Etiquette, by Emily Post, 1922

Chapter 1 The Missing Boy

Claire, 1960

If Claire had to look back and decide why she had the affair in the first place, she would point to the missing boy. This was in mid-June, during those first humid days when the air in Virginia hangs thick. School was coming to an end, and from her kitchen window Claire could see the bus stop at the corner and the neighborhood children, sweaty in skirts and blouses, khaki trousers and damp cotton shirts, pile out of it like a lazy litter of puppies. Their school bags dragged along the sidewalk; their catcher’s mitts drooped. Jump ropes trailed behind a small group of girls, as if even they were too hot.

Watching this scene, Claire smiled. Her hands in the yellow rubber gloves dipped into the soapy dishwater as if on automatic. Wash. Rinse. Set in the drainer to dry. Repeat. The kitchen smelled of the chocolate cake cooling on the sill in front of her. And faintly of her cigarette smoke, and the onions she’d fried and added to the meatloaf. Upstairs, Kathy napped, clutching her favorite stuffed animal, Mimi, a worn and frayed rabbit.

A stream of sweat trickled down Claire’s armpits. Was it too hot to eat outside? she wondered absently, still watching the children. It was hard for her to imagine that in a few years Kathy would be among them, clamoring onto the bus at eight-fifteen every morning, her braids neat, her socks perfectly rolled down, and then, like these kids, appearing again at three-thirty, sweaty and tired and hot.

That June was when Peter had said he was ready for another child, and Claire had stopped inserting her diaphragm before they made love. She wanted more children. The families around them in Honeysuckle Hills all had at least two, more likely three or four. Like divorce, only children were rare and raised eyebrows. Everyone suspected that the mother in a family with an only child had female trouble of some kind.

After all, it was 1960. The country had put war behind it. New houses were springing up around the city, in Arlington and Alexandria, clustered together in neighborhoods like Honeysuckle Hills, neighborhoods with bucolic names like Quail Ridge and Turtledove Estates. They had wide curving streets, manicured lawns, patios with special matching furniture. Men wore suits and fedoras and overcoats to work in D.C.; the women vacuumed the wall-to-wall carpeting that covered the floors. They polished furniture tops with lemon Pledge and baked casseroles with Campbell’s soup and canned vegetables. They went to the hairdresser every week and got their hair sprayed and flipped.

On long summer evenings, the families sat outside watching their children bike up and down the streets, or balance on scooters or roller skates. The girls chanted songs as the sound of their jump ropes slapping the pavement filled the air, beside the whir of lawn mowers and the distant noise of someone’s radio. On Saturday afternoons, adolescents gathered, clutching bath towels and shaking their still soft bodies trying to learn the Twist. They walked on a mat with plastic footprints, doing a clumsy cha-cha.

Even now, Claire could hear Brenda Lee crooning “I’m Sorry” from someone’s transistor radio. The dishes done, the children from the school bus dispersed, Claire removed the rubber gloves and touched the top of the cake to see if it was cooled enough to frost. Not quite. Soon enough, Kathy would wake from her nap, a little cranky, and insist on sitting on Claire’s lap, keeping Claire immobile and unable to get anything done. She glanced at the clock. If she was lucky, twenty minutes stretched before her with nothing to do. She thought briefly of the basket of laundry waiting to be folded, the summer linens that needed to be aired before she put them on the beds.

But instead of doing any of these things, Claire poured herself a tall glass of ice tea, adding ice cubes and saccharin and a sprig of mint she kept in a glass by the window. She grabbed the new issue of Time with its stark cover of an illustration of a woman and the headline: THE SUBURBAN WIFE. A yellow banner across the corner reported that one third of the nation lived in the suburbs. Settling onto the chaise lounge in the backyard, Claire glanced at the lead story.

“The wreath that rings every U.S. metropolis is a green garland of place names and people collectively called Suburbia. It weaves through the hills beyond the cities, marches across flatlands that once were farms and pastures, dips into gullies and woodlands . . .”

Really, she thought as she flipped the pages of the magazine, who needed to read a description of her own life? Her own happy life, she added as she took in bits of information. The Negro songstress Eartha Kitt got married. So had Mussolini’s daughter. Judy Holliday and Jimmy Stewart both had new movies opening. President Eisenhower was off to Japan—he always seemed to be off somewhere, Claire thought—and the Prince of Cambodia needed to lose twenty-two pounds.

She closed the magazine and set it on the grass beside her chair. The smell of roses was heavy, almost hypnotic. Claire heard bees. Across the Parkers’ yard next door, she could see a gaggle of boys walking down the street, the tops of their summer buzzed haircuts shining in the late afternoon sun. She recognized them all, and took comfort in the familiarity of her surroundings. A white car passed the boys, then disappeared around the corner. Closer now, the kids’ voices grew louder, their excited tone one that only children can have. They were talking, from what Claire could glean, about going to the moon.

That white car appeared again, slower this time. Probably someone lost in the maze of streets that made up Honeysuckle Hills. People used to the grids of city streets, the logic of numbers and letters, got confused when they had to navigate Mulberry, Maple, and Marigold Streets.

Kathy’s sharp wake-up cries cut through the air, halting Claire’s private time. Forgetting the tea and the magazine, Claire made her way back inside, up the stairs to Kathy’s room.

“Bad Mommy,” Kathy pouted.

Claire patted her daughter’s bottom to be sure she hadn’t wet the bed. Dry. A small victory.

“Come here, Kitty Kat,” Claire murmured, lifting the rigid girl. Kathy always woke up on the wrong side of the bed.

After a snack of graham crackers and milk and playing paper dolls, Kathy finally grew less crabby.

Claire let her help set the table, to carry the napkins and the silverware out to the patio. She taught her how to fold the napkins into triangles, and to place the forks on the left, the spoons and knives on the right.

“Four letters in left. Four letters in fork,” Claire explained.

“Five letters in right. Five letters in knife and spoon. That’s how you remember.”

Kathy nodded, even though she hadn’t yet learned to recite her ABC’s and still watched Romper Room and Captain Kangaroo every morning as Claire cleaned the house. Kathy liked to sing along with Miss Bonnie: Bend and stretch, reach for the stars. Here comes Jupiter, there goes Mars. Still, Claire didn’t think it hurt to spell words and explain complicated things to her now. Maybe it would help her understand eventually.

“Now it’s time to make Daddy’s martini,” Claire said.

Kathy padded back inside right behind her, climbing her little stool so that she could reach the counter. Claire carefully measured the gin and then the vermouth, letting Kathy pour the jiggers into the shaker.

“Shake, not stir,” Kathy said proudly.

Claire laughed. Her daughter might not know her ABC’s, but she knew the secret to a good martini.

“That’s right, Kat,” Claire said.

By the time the martini was chilled and the cheese was sprayed onto Ritz crackers and the potatoes mashed and the canned green beans warmed, Peter’s car pulled into the garage. Everything right on schedule.

Looking back on that evening, Claire tried to find the beginnings of a rupture, the way they say the San Andreas fault is already cracked and over time shifts more and more until the earth finally cracks open. But she could never find even a hairline fracture. She remembers feeling satisfaction over the dull predictability of her days. If she did not feel a thrill at the sound of Peter’s key in the front door each evening, she did feel a confidence, a rightness, to the way the hours presented themselves.

Peter walked in, handsome, a bit slumped from his day having the admiral rant at him and everyone around him. They both took pride in the fact that Peter was the only civilian who worked for Admiral Rickover at the Pentagon, an honor that made up for the admiral’s erratic behavior and famous temper. Peter kissed Claire and Kathy absently on their cheeks, loosened his tie, and took his place on the turquoise couch he hated, waiting for Claire to appear with that martini, now perfectly chilled. She always wet the glass and placed it in the freezer so that it was frosty and cold too. For herself, she poured a glass of Dubonnet, adding ice and a twist of lemon. On a warm night like tonight, Kathy got Kool-Aid, poured from a fat round pitcher with a face grinning from it.

“I thought we’d eat outside,” Claire said after settling onto the pink chair across from him.

“Mmm,” Peter said, already distracted by something in the newspaper he’d opened on the coffee table.

“Eisenhower’s off to Japan,” Claire said, because a woman always needed to keep up with current events.

Peter gave her a half-nod.

“Doesn’t it seem that he’s always off somewhere?” Claire said. “I read somewhere that he’s traveled almost one hundred thousand miles in his presidency.” Of course she knew exactly where she’d read it. Just a couple of hours ago in the new Time magazine.

“Well,” Peter said. “He is the president.”

Claire handed Peter a cracker, admiring the squiggle of cheese on top. Ever since she had first bought cheese in a spray can, she’d gotten better at making even lines or perfect bull’s-eyes. One afternoon, her neighbor Dot had all the neighborhood women over for Grasshoppers and a lesson in how to use the damn spray can of cheese. That had done it, even though the Grasshoppers made her half drunk and Peter came home to find her asleep on the sofa, no dinner made and a tray full of dozens of crackers and cheese.

She watched as he popped the whole thing in his mouth without even looking at it.

“Did you know, darling,” Claire said, “that one third of the nation is living in the suburbs now?”

At this, he looked up at her, impressed or surprised, she wasn’t sure which.

“Is that so?” he said.

Claire nodded.

In the weeks to come, she would hear him repeat this statistic

like he knew something about it. Like he had discovered the fact himself. By that time, she had already begun to dislike him, so this boasting made her hate him even more.

It was after dinner that Joe Daniels appeared in their yard, looking worried and hot.

Claire and Peter were still sitting at the patio table, sipping B & B. Claire had already put Kathy to bed, and the evening was winding down in that gentle way June evenings do. Peter’s stockinged foot ran lightly up Claire’s bare calf, a sign that he would want to make love tonight, despite the heat. She thought fleetingly of the fans still up in the attic. The heat had come on suddenly and she’d been unprepared. She wondered if she might convince Peter to get them down. Or at least to put one in their bedroom. The thought of him sweaty on top of her was not appealing.

His foot moved up and down, up and down. His cigarette was almost finished. If she could move this along, they might be done by ten, in time for Hawaiian Eye. With that in mind, Claire inched her chair closer to her husband’s and put her hand on his thigh.

“Hello!” Joe Daniels called into the yard.

Claire jerked her hand back and got quickly to her feet, her face hot as if they’d been caught actually doing something.

Peter got to his feet, one hand already extended to shake Joe’s. But Joe didn’t seem to notice. Instead of looking at either of them, his eyes swept the backyard.

“Joe,” Claire said. “Would you like to join us for a B & B?”

“No, no,” he said. “I’m looking for my boy. For Dougie,” he added.

Claire detected panic rising in his voice.

“He didn’t come home for dinner,” Joe said, “and Gladys is practically hysterical. She’s called just about everybody and no one’s seen him.”

“I saw him,” Claire said. “This afternoon.”

She pointed to the chair where she’d sat and read the Time magazine, which still lay in the grass where she’d left it. Claire made a mental note to bring it inside or it would get soggy and Peter would complain that she was careless.

“He was with a bunch of boys talking about space, about going to the moon,” Claire told Joe.

For a moment, Joe looked relieved. But then his face grew worried again.

“When was that?” he asked.

“Around four,” Claire said.

“Are you sure?”

“It was right before Kathy woke up from her nap,” Claire

said. “I came out for a breather.” She pointed to the magazine and the abandoned glass of ice tea.

“All right,” Joe Daniels said, nodding. “All right. But then, where could he be now?”

Claire had no answer for that.

“You know how boys are,” Peter said. He touched the other man’s arm. “He’s probably catching frogs or fireflies or some such.” Joe nodded again. “It’s just so late, that’s all. Almost

nine-thirty.”

“Is it that late already?” Claire said, thinking not about Dou-

gie Daniels but about how she would certainly miss Hawaiian Eye tonight.

“And it’s a school night,” Joe said.

“I hate to bring this up,” Peter said quietly, “but have you called the police?”

Joe gulped air as if he were a drowning man.

“I guess that’s the next step,” he said.

“I’m sure Dougie is fine,” Claire said brightly. “Boys will be boys.”

“It’s just so late,” Joe said again.

The whole time that Peter and Claire made sweaty love later that night, the teenage girl next door played the same song over and over. It started with a train whistle, then a vaguely familiar voice sang about giving ninety-nine kisses and ninety-nine hugs. As soon as the song ended, the girl played it again. She must have just gotten the 45, Claire thought, not liking the song or her husband’s sweat dripping on her. Finally, his thrusts quickened and she heard that welcome long low grunt.

“That was nice,” she whispered in his ear once his breathing had evened.

Peter kissed her, right on the lips the way she liked, the way she wished he kissed her more often. But usually she only got these kisses afterwards. She kissed him back anyway. Why was it that as soon as he finished, she began to feel stirrings? Even now, too hot and too sweaty, she held him tight, her mouth opening, something in her tingling.

“Whoa,” he chuckled. “I just finished.”

“I know,” Claire said. “I just . . .”

She just what?

“I just love you,” she said, though that wasn’t what she meant at all.

He rolled off her and lit a cigarette.

“Want one?” he asked.

“All right,” Claire said.

Peter handed her that one, and lit another for himself. She always liked when he did that.

The 45 started up again.

“I can’t tell if Peggy’s just fallen in or out of love,” Claire said.

“She’s playing that record so much, it must be something.”

She inhaled and closed her eyes. An image from that after noon floated across her mind.

“Peter,” she said. “When I saw the boys this afternoon—”

“Boys?”

“Dougie Daniels and the others. There was a white car driving around the neighborhood. A car I didn’t recognize.”

“Are you sure?”

“I thought he was lost.”

“So you saw the driver?” Peter asked her. He was sitting up now, and pulling the phone onto his lap.

“I don’t know,” Claire said, straining to remember.

“You said you thought he was lost,” Peter said as he dialed the Danielses’ number.

All of the neighborhood’s phone numbers and emergency numbers were right there on the phone, neatly typed and alphabetical.

“I just meant the driver came by a couple of times, real slow.”

“Joe,” Peter said into the receiver. “Sorry to call so late but Claire just remembered that when she saw Dougie this afternoon she also saw a white car—”

Peter glanced at Claire.

“A Valiant maybe?” she said, shrugging. “Or a Fury?”

“Really?” Peter said into the phone. “Well, I’ll be damned. Call us if we can be of any help.”

“The boys reported it too,” he said after he hung up. “They all noticed that car. D.C. plates apparently.”

He kissed the top of her head and turned off the light.

“Did someone take Dougie?” Claire said into the darkness. “I’m afraid that might be what happened,” Peter said. “Joe said the cops were leaning in that direction.”

“Someone kidnapped Dougie?” she said. Her heart beat too fast. She could hear it.

“Don’t think about it,” Peter said sleepily. But that was when it all began.

That Saturday night was the dinner party at Trudy’s when she first met Miles Sullivan. By then, her world had already started to shift. Peter looked different to Claire. Rather than comforting her, the similarity of her days made her edgy. She kept thinking back to that afternoon, to the tops of the boys’ heads, their new summer buzz cuts, the white car circling them. Circling the neighborhood.

The heat grew worse. The air felt like pea soup. And still the police could not find Dougie Daniels. The boys had given a description of the driver to the police. A short olive-skinned man with close-cropped curly hair and a plaid short-sleeved shirt. He had slowed down, they reported, and looked right at them, taking in the sight of each of them before driving past.

Claire sent a pan of lasagna to the Danielses’ house. The next week she sent an angel food cake. No one knew what else to do, and the food piled up on the Danielses’ kitchen table and refrigerator shelves and in their freezer. At night when Peter reached for her, despite the now-installed window fan, Claire squeezed her eyes shut and tried not to think about how much she wanted it to be over. When he kissed her afterwards, she did not hold him tight and kiss him back.

Two weeks after Dougie disappeared, Trudy had a cookout and Claire drank too much sangria. She felt sloppy and silly, and when Roberta’s husband accidentally brushed against her as he walked past her in the hall, it seemed as if he had electrocuted her. She studied him drunkenly. Claire had never found him attractive before. She had never considered his looks at all. But suddenly he seemed not only attractive, but desirable. Such a different type than her tall, angular husband. Ted was beefy and ruddy-faced, with unnervingly light blue eyes. She smiled at him.

“We are all so drunk,” he said.

Back at home, in bed, the room spinning slightly, Peter reached for her.

“Kiss me right on the mouth,” she whispered, and when he did as she asked a need in Claire seemed to make itself known. Dougie Daniels had been kidnapped and possibly even murdered. Nothing in the world made sense anymore, and Claire felt like an idiot for having lived so safely, for having believed that this was what she wanted: this man, this house, this life.

That night, when he finally moved on top of her, Claire’s hips met his thrusts. Her fingernails dug into his back. Something was happening to her. Something, finally, unexpected. It wasn’t Peter who let out that predictable groan, but Claire. More a yelp really, as waves seemed to grab hold of her and not let go.

In the morning, hungover, Claire felt embarrassed about what had happened. She could not meet her husband’s eyes. Instead, she scrambled his eggs, made his toast, squeezed oranges for juice, all the time wondering what in the world was she going to do next.

Of course all the mothers of Honeysuckle Hills watched their children more closely after Dougie Daniels went missing. They stood on street corners and front steps, making sure their own sons and daughters arrived wherever they were going and then back home, safely. They made casseroles and cakes for the Danielses, but they didn’t linger when they delivered them. To see Gladys Daniels, her hair unwashed, her eyes wild with grief, made them nervous, the way they had been before Dr. Salk calmed them down with the polio vaccine. If Dougie Daniels, an ordinary boy, a B student and average second baseman in Little League, could be kidnapped, then anyone could.

“It’s not contagious,” Claire said one afternoon to Roberta and Trudy. “We should go and sit with her.”

They were standing vigil as their own kids ran under the sprinkler in Roberta’s backyard. It had been a month since Dou gie disappeared, and there was no sign of him being found.

“She just kind of scares me,” Roberta said, her eyes never leaving her Sandy and Ricky, not once.

“I think she could wash her hair,” Trudy said primly. “They said she didn’t even bother to wash it when the newspeople went over there.”

“I think we should sit with her,” Claire said again. “I’m going to make calls for Kennedy tomorrow night, but I could go in the morning.”

“And bring our kids?” Roberta said. “That would just make her sad, to see our kids safe and sound while Dougie is . . . gone.”

Dougie Daniels was an only child. Gladys had had a hysterectomy at a very young age. Or so the women thought.

“What would we possibly say to her?” Trudy asked.

“I made her a Jell-O salad,” Roberta said. “With canned pears and walnuts.”

“That’s always nice on a hot day like today,” Trudy added. And that was the end of that.

The next night, Claire walked into an empty law office and sat beside Miles Sullivan, the man who would change everything. When Dougie Daniels’ body was found in the C & O Canal over Labor Day weekend, she wished she had gone that morning to visit with Gladys. But wasn’t it too late now? Wasn’t a dead child—a murdered child—even harder to talk about than one who had simply vanished? If kidnapping seemed possibly contagious, no one wanted to think about this even worse thing.

Claire sent flowers and a fruit basket. She signed up for the neighborhood meal rotation, leaving a casserole on the Danielses’ front steps every Thursday. The curtains were never opened, the blinds always drawn. It was as if all life had been removed from the house. One afternoon, when she dropped off a pan of chicken divan, she saw a catcher’s mitt and a bat on the front lawn. The sight of them made goosebumps climb up her arms. Had they been there all this time? Claire hesitated at the door. But then she laid the casserole, wrapped in a blue-and-white-checked dish towel, on the stairs and hurried off, avoiding the sight of Dougie’s Little League gear as she walked back to her car.

By October, when the leaves on the trees in Honeysuckle Hills had turned scarlet and gold, the Danielses had moved away. At first, no one bought their house—Who would? Roberta had wondered aloud, and all the women had nodded, understanding that a house where a murdered child had lived was of course undesirable—but two weeks before Christmas a new family moved in. The wife was pregnant with twins and on bedrest, but the husband was friendly. He could be spotted shoveling snow, or hanging Christmas decorations. He always waved when someone went past.

If Dougie Daniels had not gone missing, kidnapped practically right in front of Claire’s eyes, she thought it was possible that she would still be moving through her life as she had been, in a pleasant, mind-numbing routine. But Dougie did get kidnapped. And after that afternoon, nothing felt the same to Claire. Nothing felt right anymore. Until Miles had looked at her in that way. Then something shifted. Not into place, but rather completely off-center. Claire had recognized it, and jumped in.

The Obituary Writer

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393346773

- ISBN-13: 9780393346770