Excerpt

Excerpt

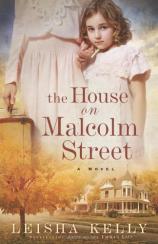

The House on Malcolm Street

Leah Wiskirk Breckenridge

September 1920

I plopped Mother’s old carpetbag next to the railing and grabbed for Eliza’s thin glove. “Don’t step too close, please. The train is almost here.”

“I won’t, Mommy,” little Eliza promised, her rounded cheeks flushed pink with excitement. “I just want to see.”

Our other bag, still slung over my shoulder, was weighting me terribly, and I tried to shift it. Here we were on the wide oak platform, though I would have preferred to run the other way and never come near this or any other train station. My feet hurt, I’d grown hot despite the coolness of the day, and though I’d tried to fix my hair as best I could out-of-doors this morning, such a long walk in the breeze surely had it looking disheveled again. I would have liked to be almost anywhere else, at least to have some other option. But despite all my fretful efforts, I could think of none.

Six-year-old Eliza, whom I sometimes called Ellie, was just as eager in this new experience as I was wary. Her rag doll dangled limply in her free hand as she strained forward in an effort to see the approaching locomotive through the press of the crowd gathering around us.

“How big is it, Mommy? Is it really, really big?”

“Yes. Terribly. You’ll see soon enough.”

The train whistle blared, painful and shrill, piercing right through me. Clouds of steam and dust rolled toward the platform, and my heart fluttered violently in my throat. As the locomotive roared to a stop, I tightened my grip on my daughter’s hand but then clutched as well at the iron rail to squelch the urge to snatch her up and flee. Little Eliza would not have been so thrilled with the prospect of a train ride, nor even with the sight of the awful thing, if she knew everything that I knew about trains.

“Mommy, Mommy! Can’t we go closer?”

“No! We must wait till it is stopped completely!”

The huge black locomotive slid nearer, churning out plumes of smoke, steam, and choking dust. For a moment it seemed to be coming straight for me, and I could scarcely breathe. The whine of the great wheels grinding to a halt jarred me to the core of my being. It was utter foolishness to come to this train station, even for the hope of a fresh start. How could I go through with it?

“When can we get on?” Eliza persisted.

I froze, trying to regain composure. My grip on the rail was painful now but my knees were so weak and my head so unsteady I was afraid to loosen it.

How had John felt when he’d stood here on this platform? I could hardly think of him without tears filling my eyes, but in this place it was even harder. Why did it have to happen? We’d had so little time together!

“Mommy, don’t squeeze me so tight.” Eliza squirmed uncomfortably.

“I’m sorry.” I relaxed my grip, took a deep breath. John would always do what he had to do. No matter how hard it was. He would never let fear stand in his way. Especially foolish, irrational fear like mine.

Eliza stared up at me. “Are we really going to ride?”

I nodded, mustering all the courage I could. “Yes. We are going to Aunt Marigold’s in Illinois.”

“Marigold is a lovely name,” she mused.

I sighed. My dear daughter had always been quick with bright and cheerful observations. I could only hope Marigold McSweeney’s disposition matched Ellie’s enthusiasm. All the women in my husband’s family had been named for flowers, including his long-deceased mother, Azalea. There was a Daisy. Petunia. Violet. Even Zinnia. That John and I had given our little girl “Rose” for a middle name might not be good enough among such folk. Marigold had written a letter recommending the name “Peony” before Eliza was even born.

I had no idea what to expect at Marigold’s, but we couldn’t stay here in St. Louis. After John’s death I’d tried to find work, but it was next to impossible with no one to care for my children. And then the influenza that had killed so many in 1918 and 1919 took another dreadful sweep through our neighborhood. I became gravely ill, and late in January little Johnny James had died. If I’d not had Eliza, I would have wanted to die too. The landlord had been patient for a while, but we lost our home when a businessman offered him more for it than he was willing to turn down. I’d already been selling our furniture and household items for the money to live on. We barely had anything left. Not enough to find another home on our own, not even for the first thirty days. Aunt Marigold did not know all of that. And yet she’d invited us months ago to the large home where she took in boarders. She’d offered to let us stay until we could get a fresh start. It had seemed like such a strange proposition when I first got the letter last winter. I’d never met Marigold face-to-face, had never been any farther into Illinois than Alton. But now, what option did we have? I couldn’t move in with my father. I absolutely could not put Ellie or myself through that, ever.

The station platform grew more crowded now that the train had stopped. Where had all these people come from? I knelt beside Ellie and drew her close, just to be sure of her in the press. City crowds still made me nervous, despite my years in St. Louis. If there was one thing positive about having to start over in Illinois, it was that I’d be in a small town again, no bigger than the one nearest the farm where I grew up.

“Are all of these people going to ride the train with us?” Eliza asked.

“No. Some are surely here to greet people just arriving, or to say good-bye to their loved ones going away.” She looked around uncertainly. “Did anyone come to tell us good-bye?”

“No.” There was nothing else to tell her. Who would come? We’d already said good-bye to Anna Butler, our former neighbor, days ago. Father didn’t know we were leaving, and we had no other family.

We watched and waited as people began to exit the train. I had already been told that this train would not linger long. Soon there was a general press toward it and then a shouted announcement for passengers traveling east.

I picked up the carpetbag that along with my heavy shoulder bag held what little remained of our belongings. We’re destitute. Relying on the mercies of John’s relative. Where is God in all of this? Where was he when we needed him so badly?

Maybe a couple of deep breaths would help calm my nerves. It would be wrong to cry in front of these strangers, and especially in front of my daughter right now. Somehow I needed to find a way to be strong and not look afraid. “Come on,” I told Eliza as cheerfully as I could. “They’re beginning to board.” It was not easy to step so near what I’d always thought of as a horrid, belching, man-eating monster. I’d heard people speak of their admiration and even gratitude for trains. But to me, from my earliest days, they’d been quite literally the stuff of nightmares, to be avoided as much as possible.

My hands shook ever so slightly, and I fought with all the strength I could muster against the threat of tears as I led Eliza through a swirl of leaves to the line where a conductor had begun calling passengers to board. I could not let myself be stopped. If we did not leave St. Louis for Marigold’s boardinghouse, if we did not get on this train, where would we spend another night? In the park again, among the birds and beasts, and who knew what else, wandering the city after dark? I could not do that to my daughter. Nights would be so much colder soon. I had to find a way for her, even if it was with a strange woman in an unfamiliar town.

Eliza bounced up and down as though we were in line for a carnival ride. She was a boisterous little girl, despite our sorrows less than a year ago. I couldn’t help thinking of her father and his death on a day not unlike this one, clear and beautiful with a flurry of dancing leaves. It had been a freakish accident, the result of his short train ride to Florissant to investigate a job opportunity. And as soon as I knew something had happened, I’d prayed. I’d begged God for John to come home to us safe and sound as always. But my prayers had been useless. John had died needlessly, because trains and train tracks were horrid, unpredictable places where metal and steam rule like tyrants over human life.

My heart thundered as this train blew its whistle again, as if taunting me. I tried to lay such thoughts aside when it came our turn to board. But I still found myself shaking as we climbed the metal step and moved to find a seat in the narrow railcar.

“Mommy,” Ellie begged. “I want to be by the window so I can look out the whole way!”

“Just sit down wherever you find a place and hold on,” I whispered.

She looked at me and dropped to a passenger chair in an empty row but then slid over until she could look out easily. We didn’t start moving. Not yet. I sat beside her, stiff and uncomfortable, wishing the ride would start so it could just be over. A ghastly scene flashed into my mind of blood, a mangled leg. Trains were killers, pure and simple. How could I possibly endure riding miles in the belly of one with such memories assaulting me? It’s just too soon. That’s the problem. Ten months is not enough time to feel normal again after losing my precious husband. And then our only son.

I sniffed, at the same time arranging our bags near my feet and hoping Eliza did not notice the trouble I was having. I could not imagine being happy about a train ride when I was six. At that age, giant locomotives had pursued me in my dreams, and even in my waking hours the sound of their whistle had given me chills.

But I was grown now. Despite the circumstances of John’s death, it was time to block such things out of my mind. I opened one of our bags and pulled out a comb to fix my hair and Eliza’s. Hopefully, we wouldn’t arrive at Aunt Marigold’s looking like vagabonds.

We certainly didn’t have much baggage to speak of. The conductor had offered to place it in a baggage car for me, but I wanted to keep everything by my side. We had so little left in this world. Clothes. A few pictures and personal items, nothing more. I’d had to sell what little else we’d had in order to purchase the train tickets.

Hopefully the two nights we’d spent without shelter would be our only ones in such condition. We had no money for a return trip, but what was there to come back to? A park bench? Our first night on one of those had been horrid. I’d felt so empty and hopeless. I’d hardly slept, struggling to make up my mind what to do. The second night was just as unnerving because of a man I’d seen watching us from a distance. But he went away and I found some peace in my decision to leave Missouri and show up on Aunt Marigold’s doorstep. She’d offered. And I’d have to be brave and humble enough to accept the offer. If I’d only known to arrive at the station for the early train in the wee hours of morning, we could have been there by now.

Eliza was more aware than I wanted her to be of my quiet thoughtfulness. And despite her excitement to be taking this trip, she was probably nervous as well. She leaned into my shoulder and gently stroked my hand. “Are you sad today, Mommy?”

“A little.” I sighed. I really hated to admit such a thing, but there was no point denying it when she seemed to read me so easily.

“You wish Daddy and baby Johnny were here?”

Sometimes my daughter’s directness was more than a little unnerving. She seemed terribly grown-up in moments like this, and I knew she wanted me to be honest. So I nodded and tried to sound as positive as I could. “I’m sure it’ll be wonderful for us in Illinois. But in a way I feel that we’re leaving them behind.”

“Anna told me they’re always with us,” she said softly and turned her eyes to the window where we could easily see over the heads of the people remaining on the platform outside. I sat in silence. How could I possibly respond? Despite Anna’s words, John and the baby were not with us and would never be with us again. Nothing would ever be the same, or feel right again.

I leaned back and closed my eyes, holding Eliza in my arms as the train began its slow crawl forward. Maybe if we sat very still and were both very quiet as the train began its acceleration, I wouldn’t get too anxious, nauseous, or upset. Soon we’d be rushing out of the city and into the countryside, leaving St. Louis and its memories forever behind us.

“Will we sleep on the train tonight?” Ellie whispered.

“Not all night,” I answered, hoping my little girl would be satisfied with the vague reply. I simply couldn’t discuss things more. Not yet. I had to regain my equilibrium, my composure, first. We were riding in a ten-ton monster. Maybe even the very one that had killed John. There was no way to know for sure. Ellie continued her words at a whisper. “I think it will be lovely to sleep on the train, even if it’s just for a little while.” She squeezed my hand. “But I wasn’t scared to sleep in the park. Not one bit. That was a good adventure too.”

Adventure. Of course that was the way a six-year-old would see the state our lives were in right now. Lovely. I smoothed her brown muslin skirt and glanced at the heads of the couple in the seat in front of us, hoping that no one had heard her speak of sleeping in a park. Before we reached Andersonville, I must tell her not to mention a word of such things to Aunt Marigold. That we were destitute and coming so suddenly to share her roof was shameful enough.

I’d thought that Eliza would be tired and ready for a nap once the train got going. She’d been up far too early this morning and couldn’t possibly have slept well overnight on the wrought-iron bench I’d chosen to keep her up off the ground. It had been a tiring day too, walking all the way to the mission church where I knew breakfast would be served, past the memorial garden where John and the baby were buried, and then across the city to the train station.

But she was far too interested in the view out the window to consider closing her eyes for even a moment. Did she remember being anywhere other than the city? Maybe not. She’d only been two the last time we’d ridden out to Sugar Creek, where I grew up.

It seemed like only yesterday. A beautiful April morning. John had driven the shiny Ford coupe he’d gotten from his best friend, trying not to be edgy about taking us out to see my parents for only the second time in our marriage. And I’d been far more nervous than he. Of course I’d longed to see Mother, but I’d never had a good relationship with Father. Walter Wiskirk had despised my choice of a husband from the beginning, and he made no effort to hide it. He’d scoffed when we chose to name our girl Eliza, after my mother, but he’d been even more spiteful when we’d named our second child John James. He scarcely knew how to be civil to anyone.

Life and death were so cruel. I needed my mother. I would have loved to have her at my side right now. And Ellie would have loved it too. Why would God take her away, two years ago this very month? Why would he not have taken my father instead, who never bothered with a kind word, never tried to be a decent father or grandfather? He had always been red-faced and yelling from my earliest memories of him. It was good to be putting distance between us.

“Mommy, look!” Eliza cried suddenly, pointing to the wide expanse of river the train was about to cross. The mighty Mississippi. I took a quick glance and then averted my eyes so I’d catch no real glimpse of the narrow bridge that would be supporting the train’s weight over the rushing current. I need to be strong. I must be strong. I must not let fear stand in my way.

John had understood the fears that troubled me, though they’d never been as bad when he was around. He’d been patient, gentle, in praying for me and helping with so many things. But trains were absolutely the worst. They’d always been the worst.

Eliza pulled my sleeve and pointed out a small herd of cows grazing placidly within a fenced pasture. So quickly we were across the river and into the colorful leaves and drying cornfields of Illinois farmland on the other side. I did my best to smile and nod pleasantly for my daughter’s sake, though the train’s steady speed was unnerving. Thirty miles an hour? I couldn’t be sure. It might have been even more. What would happen should one of those cows escape its fence and wander onto the track? I shuddered to think about it.

Ellie looked into my face for a moment, as though she sensed the unrest inside me. But she broke into a tender smile. “This is fun,” she said softly. “Ill’noy’s gonna be lovely.” There was that word again. So many things were “lovely” to Eliza lately. But that was better than “blessed,” her favorite word just a few short weeks ago. Hearing “blessed” so often had been a trial for me, a dismal struggle with my faltering faith because it constantly reminded me of God and what he could do, or should do. Or should have done.

John and I had wanted a big family. I’d always wanted a big family. And despite our hopes and prayers, that dream had been brutally stolen away. Now Eliza and I had nothing but lack. How long would it be before she grew hungry, if she wasn’t already? Hopefully, her excitement with the trip and the sights would keep her from noticing. It was long past lunchtime. But we hadn’t eaten since breakfast, and I’d had no money to provide food to bring along, nor even a penny to purchase any once the train was stopped. We’d be leaning on Aunt Marigold’s mercies indeed.

Eliza should have been able to enjoy a day at school like other children and then come home to a warm house and generous supper. But I couldn’t give her any of that yet. She would’ve started school in St. Louis if we hadn’t become homeless. But the beginning of first grade could be such a crucial time. I just couldn’t send her off for such a new thing when I didn’t know from one day to the next where we’d be. Hopefully, she could begin in Aunt Marigold’s town. And hopefully, missing the first few days would not be a problem and she wouldn’t be set back a year.

Taking Eliza’s hand to hold, I closed my eyes and leaned my head back again. I really should pray. The way Mother had taught me and John had always encouraged me. The compulsion was strong, but I still resisted. I’d been able to believe in prayer once. But I was afraid now. If I dared try again only to find disappointment, I wasn’t sure how I could take it. I hadn’t been able to pray aloud since John died for fear that Ellie would be hurt if the prayer weren’t answered. That was bad enough. But I hadn’t prayed at all since losing the baby. And silence toward heaven grew increasingly painful. Why should I pray? What had it gained us? And yet my guilt only grew stronger over not doing so. It wasn’t fair.

Eliza was quiet, looking out the window, leaving me to my thoughts. But eventually, the weariness of the day won out as she turned and snuggled with her head on my lap. I stroked her generous curls, wondering if she already knew that asking about dinner would gain her nothing. She seemed so content, so at peace. How was it possible? She was an amazing child, to be without her daddy and yet to remain so cheerful, so appreciative of everything around her. If I could just be more like her! Maybe I could get past our losses and find real hope in making a new life. I combed through her pretty hair with my fingers, at the same time watching her face. So peaceful, so trusting. She did not seem to have the slightest doubt that Marigold would welcome us and everything would work out beautifully for us there. She’s not like me. She’s like her father. Fearless and confident. Unshaken even in hard times.

I could see out of the corner of my eye that someone had approached in the narrow aisle, but I did not look up.

“Excuse me.”

The unexpected voice was jarring, and I found myself resenting the interruption. Who would disturb my solitude with my daughter or have reason to seek my attention on the train? Reluctantly, I looked up into the face of an elderly woman from a seat a few rows in front of us.

“Excuse me,” she said again, passing a large orange between her hands. “We get off at the next stop, and we just won’t be needing this.” She extended the orange in my direction.

“My husband and I thought your little girl might like to have it.”

I could barely respond. I’d have liked nothing more than to claim the orange before the woman changed her mind. I’d wanted desperately to be able to offer Eliza something to eat. But a gift from strangers?

“Are you sure?” I asked the woman quickly. “Wouldn’t you use it later if you took it with you?”

“No. If we eat it now, it’ll spoil dinner with my niece. And if we take it along to that household, it’ll cause a ruckus over how to split it among her seven children. Better to share it with someone who might need and appreciate it now. Does your little girl like oranges?”

Eliza had opened her eyes and was looking up at the woman with a smile, but she didn’t respond.

“Y-yes,” I answered, receiving the gift with a shaking hand.

“Thank you.”

“You’re very welcome. Have a wonderful trip.”

The train was beginning to slow, and the old woman and her husband made their way to the end of the car. I watched them, still holding the orange. How could they have known our need? Did we look so poor? Could complete strangers read our situation that well?

Eliza sat up, her eyes shining and her face aglow with excitement. “Mommy! God is good to us! I prayed! I asked him for something to eat, and he sent us this orange right away! Can we open it up? Right now?”

I stared at her, barely able to keep back tears. God had answered her prayer so readily? Sure, it was a good thing. The dear child needed a decent meal, and this would at least keep her from going completely hungry. But I felt anger stirring in me, deep and bitter. You think this is enough, do you, God? One orange? In the face of all our need? I begged you! I cried and prayed that you wouldn’t take first her grandmother, then her father, then her baby brother! And now you decide to send us one orange?

“Mommy?” Ellie repeated. “Can we open it?”

She looked so happy, so hopeful, her joy tempered only slightly with concern for the look that must have been on my face. I was practically shaking inside, afraid of my own feelings, yet unable and unwilling to change them. But I must not let her know. I must not pass along to Ellie the worry of my resentment and ingratitude when she was feeling so…blessed.

“Of course,” I told her, careful to smile. “I will peel it for you right away.”

“For us, Mommy,” she corrected. “I prayed for us both to get something to eat.”

I could not stop the tears from filling my eyes now as I tore into the orange rind with my fingernails. My precious, saintly daughter intended to give me half. And for fear that the tears would take charge, I could not tell her that I couldn’t eat what she alone had gained by her prayer of faith. I had no right.

“Isn’t God good?” she went on. “I never, ever seen a prayer answered so fast before.” Neither have I, my restless, embittered mind answered, fortunately not aloud. Ellie was watching my face, keenly aware of my tears.

“Have you got real hungry since this morning?” she asked. I shook my head, miserable with the understanding that she’d probably been suffering in silence. I was hungry. But I couldn’t admit it to her now. Setting the bits of rind aside, I pulled segments of the orange apart and gave her the first one. It looked so juicy and sweet. I expected her to eat the first bite quickly, but she paused, her face lit again with a smile. “Thank you, Jesus, for sending an orange when we needed one.” Now she was ready to eat. But not quickly as I’d expected. She took small bites, savoring, making it last.

“You have some, Mommy.”

I shook my head again and kept passing her the orange segments, one by one. “I’m not really hungry, dear.” It was a lie, but she’d have no way of knowing that. I was glad for her to eat it. I wanted her to eat it all, though some fire of indignation still burned hotly within me that God would do this --- send just this little gift now, as though that could make up for all the pain, all the negligence, of the last months. Today you hear? my mind raged on. Where were you in November when John was killed? Where were you in the winter when the baby and I became so sick? You brought John through the war only to come home and die the way he did! And you brought little Johnny James through a difficult childbirth only to die such a few short months later! You left Ellie and me alone, not knowing how to go on! And now --- now you hear?

My own depth of anger frightened me. I didn’t know the Scriptures very well, but there must surely be a warning there about railing and complaining against God. I knew it wasn’t right. It scared me to be in such a place, yet I couldn’t let it go. It’s not fair, God! You’re not fair!

How dare I be this way? Mother would be horrified at me. John too. They would think that I should cheerfully accept everything that had happened and keep on thanking God. Eliza was down to the last orange piece. She had tried to offer me several others, but I turned them down. “Please, Mommy,” she suddenly begged. “Please eat this one. I want you to know how sweet it is.”

Her bold words seemed almost like the voice of God telling me to open my heart and listen. I was missing something, something he wanted me to know. I swallowed hard. “Please, Mommy.”

How could I continue to refuse? She looked very near tears. Because of me. Finally, I nodded. She’d prayed for food for both of us. She did not want me to deny her answered prayer and make it only half complete. “All right,” I acquiesced. “It would be nice to have a taste.”

I ate the orange slice slowly as Eliza watched my every move. “Wonderful,” I said when I was done. “Imagine such a sweet orange in the middle of the country in September. I wonder where they got it?”

She laughed. “It doesn’t matter, Mommy. We got it from God. Isn’t he good?”

She was waiting for my answer. I nodded, knowing it was the best I could do to respond. I would not be able to argue the point with her. In a way, I still wanted to believe it myself. But my pain had built a formidable wall that grew broader and higher with each passing day. I wasn’t sure I’d ever feel the presence of heaven unhindered again.

Excerpted from THE HOUSE ON MALCOLM STREET © Copyright 2011 by Leisha Kelly. Reprinted with permission by Revell. All rights reserved.

The House on Malcolm Street

- Genres: Christian, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Revell

- ISBN-10: 0800733282

- ISBN-13: 9780800733285