Excerpt

Excerpt

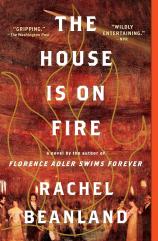

The House Is on Fire

1.

Sally

Sally Campbell’s shoes are fashionable but extremely flimsy. She ordered them from Curtis Fairchild’s specifically for Richmond’s winter season, but now she feels like a fool for thinking she could get away with wearing them on the half-mile walk from her brother-in-law’s house to the theater.

The shoes, which are made of silk and lined with linen, are as pretty as they come, but they are no match for the terrain. It’s been so cold that the earth is frozen solid, which means that every bulge and divot beneath Sally’s feet feels like a knife blade through the shoes’ thin leather soles. “It’s possible I would have been no worse off barefoot,” she says to her sister-in-law Margaret when they reach the corner of H and Seventh Streets.

A fierce wind whips at the women’s faces, and they lean into each other, drawing the collars of their coats tight around their necks while they wait for Archie to catch up. “We need you, dear,” Margaret calls to her husband as he lumbers toward them.

Archie, amiable as ever, seems pleased to be needed.

“Be a gentleman and walk in front of us,” says Margaret. Then she winks at Sally and says in a voice loud enough for Archie to hear, “We’ll let him block the wind.”

Archie gives them an exaggerated bow and touches the brim of his hat, but when he rounds the corner, he has to hold on to it with both hands. The wind comes from the east and spills down Richmond’s main thoroughfare, taking the last of the leaves on the trees with it. Margaret and Sally fall into formation behind Archie, tucking their chins to their chests.

As they pass the capitol, Sally can hear the church bells from a few blocks away chime seven o’clock. The capitol is an imposing Palladian structure, and its plaster of Paris facade shines under a canopy of stars. In the pastures that surround the building, Sally tries to make out the shapes of grazing cows. She can hear their irate grunts, carried in the wind, and knows that, in weather such as this, they are huddled close together, too.

“Just another block or two,” says Margaret, who married into the Campbell family just a few years after Sally did and has, over the past half dozen or so years, become not just a sister to Sally but a dear friend.

Margaret is such a dear friend, that she has not uttered a single complaint about venturing out in this weather. Sally knows she’d have preferred to remain at home, in front of a warm fire, but since Sally gave her hosts the tickets to tonight’s performance as a gift, Margaret is doing an admirable job pretending there is nowhere else she’d rather be.

The truth, of course, is that the tickets were as much a gift to Sally as anyone else. She loves the theater—the extravagant props, the audacious costumes, the monologues that move her to tears. Back when Robert used to bring her to Richmond, they’d gone to the theater every chance they got, but in the three years since his death, she’s had little reason to come to the capital at all, much less to see a play.

The theater sits at the intersection of H and Fourteenth Streets, catty-corner to the capitol and on the crest of Shockoe Hill. It is an impressive building, with a commanding view of the wharf. Beyond the wharf is the James River, which curls around Church Hill, winding its way past Rockett’s Landing and all the way to Jamestown.

The old theater, which was barely more than an oversized barn, burned to the ground the year before Robert and Sally were married, and for several years the Charleston-based Placide & Green and other touring acting troupes had to perform in the old market building, local taverns, or not at all. Sally and Robert saw André at The Swan and The Taming of the Shrew at City Tavern, and while it was nearly impossible to hear the actors’ lines over the din of the crowd, Sally thought the taverns-turned-theaters weren’t all bad. She liked the buzzy feeling she got when she drank down a pint of cider too fast and began reciting Shakespeare in Robert’s ear; on the nights she took his earlobe between her teeth and he called her his wee drunkard in his thick Scottish accent, they rarely made it through three acts.

The new theater has some nice upgrades: a real stage—with wings large enough to store even the most extravagant props and set pieces, an oversized pit, and a proper ticket booth. There is a separate gallery for slaves and free Blacks and plenty of box seats on the second and third floors for those who can afford them. The building is sided with brick, but it’s clear the theater’s managers cut corners on the finishings. They planked the lobby but left the rest of the dirt floors exposed; the boxes are sparsely furnished with a smattering of uncomfortable chairs and benches; the windows are so drafty they have to be boarded up during the winter months; and some nights, in this new space, the pitch of the crowd gets so loud Sally would almost swear the acoustics were better at The Swan.

When Sally, Margaret, and Archie near the theater, they find a large crowd gathered outside the building’s double doors, waiting to get to the ticket booth inside. The exterior of the building is plastered with playbills announcing the evening’s performance:

Last week of Performance this Season. Mr. Placide’s Benefit. Will certainly take place on Thursday next, When will be presented, an entire New PLAY, translated from the French of Didurot, by a Gentleman of this City, Called THE FATHER; or FAMILY FEUDS.

“Isn’t Diderot spelled with an e?” Sally asks, but Margaret isn’t paying attention.

“Pardon us, excuse me. We’ve already got tickets, we’re just trying to get inside.” Margaret removes the tickets from her reticule and waves them in the air, as if they alone can part the sea of people that stand between the Campbells and the building’s warm interior.

Inside the lobby, a Negro man wearing a short-skirted waistcoat inspects their tickets and directs the three of them down a narrow passage to an even skinnier staircase, which is crowded with people, everyone making their way to their seats on the second and third floors. As they file up the stairs, Sally pays attention to the other women’s footwear. Most of them have worn shoes every bit as silly as hers.

“So, who’s this mysterious ‘gentleman of the city’ who’s translating Diderot?” Sally asks Margaret when they reach the first landing.

“I assume it’s Louis Hue Girardin. He runs the Hallerian Academy. On D Street.”

Sally doesn’t know much of anything about Richmond’s private academies, having spent her formative years in the country. “Is that the funny building that’s shaped like an octagon?”

“That’s the one,” says Margaret before looking over her shoulder for her husband. “Archie, what was the story with Girardin? In France?”

“He was a viscount. A real royalist.” Archie is already winded, and Sally strains to hear him. “Was about to be guillotined, by the sound of things.”

“So, he fled to America?” she asks.

“Twenty years ago now,” says Margaret. “Very dramatic escape.”

“No wonder he likes Diderot,” says Sally.

When they reach the second floor, Margaret looks at their tickets, but Sally stops her and points up at the ceiling. “Our box is on the third floor.” Sally glances backward at her brother-in-law, who is bent at the waist, trying to catch his breath. “Sorry, Archie,” she says.

On the following flight of stairs, the crowd thins some, although the echo of people’s footsteps, combined with the buzz of so many conversations happening at once, still makes it hard for Sally to hear what Margaret is saying. “Girardin used to teach at William and Mary, but he’s been here for at least a decade. Married one of the Charlottesville Coles. Polly. She’s the middle daughter, I think. Anyway, I doubt Williamsburg agreed with her. How could it?” Margaret lowers her voice and Sally leans in. “Eliza Carrington was telling me she thinks the school Girardin’s running barely keeps a roof over their heads, which is too bad because, from all accounts, he is quite brilliant.”

“I would guess so,” says Sally. “Diderot isn’t easy.”

Sally’s own education was devoid of Diderot or Rousseau or any of their contemporaries. Her father, for all his intellect, had not been a particularly learned man. He was an excellent orator and statesman, but his arguments didn’t come from what he read in books so much as what he read on people’s faces. He’d practiced law without much of a legal education, then served in the House of Burgesses before the Revolution. There had been two terms as governor and a stint in the Virginia House of Delegates, and while his political life had given him plenty of wisdom to impart to his children, he was much more likely to be found rolling around on the floor with them than teaching them anything useful.

Sally’s brothers’ education had been outsourced. Private tutors instructed the boys in Latin and Greek, history and geography, until they were ready to attend Hampden-Sydney College, where none of them had proved to be especially fine students. Sally and her sisters were instructed by their mother, Dorothea, who read little besides The Art of Cookery, but had managed that singular and spectacular feat of catching a husband equal to her in wealth and rank, which—in her opinion—made her eminently qualified to educate her daughters. Dorothea taught her girls to read and write, produce neat stitchwork, and paint periwinkles and pansies that didn’t drip down the paper-thin edges of porcelain teacups. She hired a neighbor to give the girls lessons on the pianoforte and a dancing instructor who came all the way from Lynchburg to teach all the children how to dance a proper minuet.

It was Robert who had plugged the holes in Sally’s education. The first time he’d ridden out to Red Hill, to introduce himself to her father and to make a pitch for the new company store he was running in Marysville, he’d spent several minutes inspecting her father’s small library. The bookshelves contained legal treatises and law dictionaries, but few novels and almost no poetry or plays. Sally had been reading on the settee in the parlor when he arrived, and she stayed put when her father went looking for his ledger.

“Have you read these?” Robert asked, running his hands along the eight leather-bound volumes of Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa.

“All of them,” said Sally, watching him from across the room. “Twice.”

Robert looked up at her, amused. “Pamela, too?”

“Don’t be confused,” said Sally. “I much prefer novels that don’t relegate women to housewifery. But they’re few and far between. And given our geography, I’m not in a good position to be choosy.”

Robert looked out the window, in the direction of the carefully manicured boxwoods, which bordered a path that led across the yard, past the slave cabins, and down to the tobacco fields. Beyond the fields, the Roanoke River wound its way across Virginia’s Southside and all the way to the North Carolina coast. “I suppose it probably is quite difficult to get books out here,” he said.

Sally studied him. She guessed he was ten years older than her, although at seventeen, she was a very bad judge. His hair was still dark, but his skin betrayed either age, hard use, or both.

When he abandoned the window and turned to face her, his eyes gleamed. “So, if not dutiful wives, what kind of heroines do you prefer?”

She revealed the book she had tucked into her skirt when he entered the room, and he moved a little closer, squinting at the stamped foil on the cover.

“Charlotte Temple?”

“Susanna Rowson’s very clever, I think.”

“I think so, too, but if you don’t like dutiful housewives, you can do better than reading about poor Charlotte’s downfall.”

“You’ve read it?”

“Aye.”

“Most of the men I know won’t touch a novel, let alone one written by a woman.”

“Why not?”

“They say they’re a corrupting influence.”

“Corrupting to whom?” said Robert, a hint of a smirk at the corner of his mouth.

Sally had been disappointed when her father returned and their conversation was cut short. But then, less than a fortnight later, Robert returned to Red Hill with a special-ordered horse saddle for her father and a copy of Rowson’s play Slaves in Algiers for her.

“It’s not a novel,” said Robert, “but it’s clear she’s got something to say.”

After that, there had been a steady stream of books. On each of Robert’s visits, after he finished his business with Sally’s father, he came to find her. And, for her part, Sally made herself easy to find.

Sally’s father grew ill the winter she turned nineteen. As spring turned to summer and his condition worsened, the stream of visitors to Red Hill slowed to a trickle. Still, Robert continued to ride out to the property, eventually giving up even the pretense that he had business with her father.

On one visit, he brought Sally his brother Tom’s poetry collection, The Pleasures of Hope, which had just been published in Edinburgh to some acclaim. She read the poems several times over and eventually realized that she had stopped paying attention to the language—which was lovely—and had instead started to mine the book for details about Robert’s childhood in Glasgow.

There was one line that she hadn’t been able to put out of her mind, and she asked Robert about it on his next visit, when he found her under a honey locust tree, near the herb garden. “There’s this part about ‘the brother of his childhood,’ who ‘seems restored a while in every pleasing dream.’ Is he writing about someone in particular?”

Robert inspected his hands. “Aye. About our brother Jamie. He drowned in the Clyde when he was thirteen.”

“I’m sorry.”

“My brother Archie and I were already in Berbice. But Tom was six, and he was the one who found him. First his clothes, and then his body, a little further down the river.”

Sally had also lost brothers, and on days when she was being honest with herself, she could acknowledge that her father’s condition was worsening and that, soon, she would lose him, too. She felt a sudden urge to wrap her arms around Robert, to tell him that she knew something of the “hopeless tears” his brother described.

But all she said was “It’s a beautiful poem.”

It hadn’t occurred to Sally, before she met Robert, that marriage might be anything other than a series of duties, performed over a procession of years, but when they married, she had been pleasantly surprised to find she’d been wrong. In Marysville, where Robert had rented a house for them, there was plenty of work to fill her days, but there were also long, dark nights when she curled against her husband’s chest, listening to the soft thud of his heart as he read to her by the glow of a lamp. It wasn’t a bad way to be introduced to the French philosophers, all things considered.

There is a logjam in the third-floor lobby, where everyone has stopped to examine their tickets and confirm their box numbers. “We’re this way,” says Margaret, plowing her way across the lobby and down one of the long, narrow hallways that wraps around the building. Sally follows close behind.

“Pardon me,” she says as she turns sideways to let a wide-hipped woman, coming from the opposite direction, pass. Behind her, the hallway is empty.

“We’ve lost Archie,” Sally calls to Margaret as she hurries to catch up.

Margaret waves a hand over her shoulder. “I’m sure he got stuck talking to someone. He’ll find us.”

Archie is a factor and shareholder with Buchanan, Hopkirk & Co., one of Glasgow’s oldest and largest tobacco houses. The company has fourteen stores in Virginia, where planters can bring their gold leaf tobacco to sell, and in return, buy a fine assortment of imported goods against their ever-expanding lines of credit. Robert ran the store in Marysville, but his older brother’s role is far larger. Not only does Archie oversee all the company’s storekeepers, but its warehouses, too. With ships from Glasgow arriving all the time—either via the Potomac, the Rappahannock, or the James—it is advantageous for the company to maintain warehouses up and down the state’s fall line, which means Archie regularly travels between Richmond and Petersburg, Fredericksburg and Falmouth. Sally knows Margaret grows weary of it, and that she is especially grateful for the winter months, when all of his clients come to him.

Richmond in the winter is a perennial party. The General Assembly meets from early December through late January, its one hundred and ninety-five delegates and twenty-four senators presenting and voting on a year’s worth of legislation during the brief window of time when it is too cold to plant so much as a radish in the ground. Virginia’s planters travel to the capital with their families, staying in taverns and boardinghouses—if they don’t have property in town—or with family and friends who can host them. During the day, the men convene at the capitol and the women shop or call on friends who live too far afield to visit during the remaining ten months of the year. At night, there are card parties and balls and—of course—plays.

“Here we are,” says Margaret. “Box six.” She pulls aside a thick velvet curtain to reveal a box already crowded with more than a dozen people, all of whom look far less interested in the impending performance than in each other.

“Well, if it isn’t Sally Henry,” says a voice that comes from a dark corner of the box, where several men are congregated.

Sally can feel the muscles between her shoulder blades tighten. She took Robert’s name a dozen years ago now, as a girl of nineteen, but plenty of men still refuse to think of her as anyone other than Patrick Henry’s daughter.

She turns to find Tom Marshall smiling at her.

“Mr. Marshall,” says Sally, offering him her hand and a shallow grin.

Tom is a congenial man, whom Sally knew best when they were children and their fathers regularly sat on the same side of the courtroom together. When the Henrys lived at Salisbury, the families saw each other with some regularity.

“Still as gorgeous as a Greek goddess.”

“Don’t lie to me.” Sally is a becoming woman, although she believes that, at thirty-one years old, she’s lost the privilege of being called gorgeous. Her hair, which has always been dark, still falls past her shoulders in loose waves, but now there is a single streak of gray that is hard to hide when she rolls the curls that frame her face. Her eyes are a dull gray—not blue like her sister Dolly’s—and while Sally was proud of her pale complexion as a girl, Robert’s finances were never so secure that she could afford to stay out of the sun. In the nine years she was married, her skin turned a golden brown.

“Margaret, you know Tom Marshall?” Sally asks, almost certain that she does.

“We met at the races. Was it last year or the year before?”

Tom takes Margaret’s hand, then asks after Archie. Before Margaret can explain that he is on his way, Tom cuts her off. “Do you both know my cousin, Edward Colston?” Margaret does, Sally does not. “And then, this fine fellow is my good friend Alexander Scott.”

Sally does not know that she would have described Mr. Scott, who wears an oversized cravat and leans on a sword cane, as a fine fellow. He is probably no older than Robert was when he died, but he carries himself like an old man. Whereas Robert was sturdy, with cheeks the color of cherries, Mr. Scott is pale and so thin he looks ready to blow over in a strong breeze. He wears a beard, which obscures his mouth completely, and his shoulders are so stooped she is tempted to treat him like one of Margaret’s children and tell him to stand up straight. All that being said, he has nice eyes, which counts for something.

“Are you any relation to Richard Scott?” Margaret asks. “The delegate from Fairfax County?”

Mr. Scott shakes his head no. “I know him. I think he’s here tonight, in fact. But I can’t say I’m related to him.”

“Mr. Scott is himself serving in the Assembly. He’s in his first term,” says Tom.

Margaret gives her new acquaintance an appraising look, as if she hadn’t quite seen him before. “House or Senate?”

“House.”

Mr. Scott seems unwilling or unable to supply further information on the subject, so Margaret asks, “For which county?”

“Fauquier.”

This might have been the right time for Mr. Scott to offer the women some cursory details about his life, or to ask them something about theirs. Instead, he fumbles with the watch fob that hangs from his waistcoat and checks the time. Margaret is not one to be easily put off, so she makes a show of looking around the box. “And is your wife with you this evening?”

Sally presses the toe of her shoe on Margaret’s foot. Her rule, when she accepted Margaret’s invitation to come to Richmond for the season, was that there would be no matchmaking.

“I’m here alone,” says Mr. Scott.

The answer is evasive, and Sally knows Margaret won’t like it, so she tries to steer the conversation into safer waters. “Do you like Diderot?”

Mr. Scott blinks at Sally. “Not particularly.” She waits for him to continue, to argue that Diderot was an atheist or even that his plots are flimsy. But he doesn’t justify his position.

Margaret can’t let him off the hook. “Is there perhaps another playwright you find more appealing?”

“I’m not much for plays,” he says and looks relieved when Archie announces his arrival in the box with a booming “What have I missed?”

There are more pleasantries and the puffing up of chests, the display of plumage. Sally removes her coat and, noting that the men have taken all the straight-backed chairs, secures an empty bench that has been pushed up against the box’s railing. She pulls it out and takes a seat, placing her jacket and a small handbag beside her.

Over the next few minutes, Sally watches the theater fill.

The pit, two stories below, is a sea of people who never stop moving. Tickets to the pit are cheap, and the seats are few and far apart, so most people abandon them altogether, choosing to spend the duration of the performance on their feet, mingling with their neighbors. At the front of the pit sits the orchestra, its members tuning their instruments to the hum of the crowd.

Sally can’t get a good look at the colored gallery, not from where she sits, but she can see into the boxes on the opposite side of the theater. She’s searching for people she knows. None of her brothers and sisters, with the exception of Fayette, spend much time in Richmond, but her cousins—particularly on her mother’s side—do. Lots of the girls she grew up going to parties with in Lynchburg and Farmville have married well enough to spend Christmas in the capital.

Margaret joins Sally and whispers in her ear, “That Mr. Scott’s quite the Don Quixote.” Then she gives Sally’s shoulder an affectionate bump, and Sally puts her head in her hands and lets out a low laugh that could easily be mistaken for a growl.

“What do I keep telling you?”

“I know, I know,” says Margaret. “You’re not ready.”

“And when and if I am,” Sally says, tossing a quick glance behind her, “please, God, not him.”

Margaret lets out a loud sigh.

“But I do appreciate it,” says Sally, trying to be serious.

“I just want to know that you’re going to be all right. You can’t live with your mother forever.”

“Can’t I?” Sally says, and both women allow themselves an earnest laugh.

It was universally acknowledged, among Sally’s friends and family, that she had been right to let go of the Marysville house. She stayed on there for more than a year after Robert died, but without the store, she had no income; it soon became obvious that the rent would deplete what little she’d inherited.

Sally thought about returning to Red Hill, but by then her mother had remarried and gone to live at her new husband’s home in Buckingham County. The Red Hill property, which Dorothea would have been entitled to keep until her death, had she not remarried, went instead to Sally’s youngest brothers, who were ill-equipped to manage a henhouse, much less an entire estate.

When push came to shove, Sally had stored her furniture and household goods at Red Hill and sent her personal effects to her mother’s. Then she’d packed a trunk and gone visiting. Her friends and relations were always happy to have her and she worked hard to be useful and to never overstay her welcome. Still, over the last two years, she’d grown weary of the constant travel and longed to settle down.

“My mother’s got a piece of property, Seven Islands, that my father intended for one of us girls.”

“Where is it?”

“Halifax County. Just across the river from Red Hill.”

“Wouldn’t you be lonely, out there all by yourself?”

Sally doesn’t have a good answer to that question. Maybe Margaret doesn’t realize that she always feels lonely, even when she is surrounded by people, even on a night like tonight. Especially on a night like tonight. “I’d have Lettie and Judith. And Andy.”

“Sally Campbell,” says Margaret, as if she is scolding one of her children. “Your slaves do not count.”

Behind them, Tom Marshall says something that puts the rest of the men in stitches.

Sally lowers her voice. “What choice do I have, Margaret?” It took her stepfather the better part of a year to unravel Robert’s finances and to convince a judge that, with no heirs, Sally deserved more than the dower’s share of her husband’s estate. He won her the household furniture, the livestock, Robert’s meager savings, and the couple’s slaves, which didn’t feel like much of a victory considering Sally had been the one to bring them to the marriage in the first place.

Margaret presses her lips together and casts her eyes about the theater, as if she is looking for a good distraction. She points at the box directly across from theirs. “That’s the governor and his wife.”

“The man with the big stock buckle?” Sally doesn’t recognize him, but then again, she hasn’t been to Richmond since he took office. “He’s handsome.”

“Oh, I don’t know—you don’t think his forehead’s a little high?”

Sally cocks an eyebrow in her sister-in-law’s direction. “Getting quite particular in your old age?” Archie, who is in his early fifties, is short and stout with a receding hairline and three chins where there was once only one. Sally thought Archie attractive when they first met, more than a decade ago, but the last few years have not been kind to him. She can only assume that Margaret, who is twenty years younger than him and quite comely, has noticed.

A small boy sits between the governor and his wife. “They have just the one child?” she asks Margaret.

“God, no. Seven or eight, I think. But they’re all his from his first marriage.”

Sally and Robert had wanted children. Sally, in fact, had been desperate for them. But each month, her courses had come like clockwork.

Her older sisters promised that if she swallowed three spoonfuls of honey each night, right before bed, she’d be pregnant in no time. But a year passed, and nothing happened. Soon, Sally was poring over Buchan’s Domestic Medicine and Culpeper’s Complete Herbal and English Physician and writing away to apothecaries in Philadelphia and even London for the herbs and extracts they prescribed. Over the next several years, she consumed dozens of tonics and teas, before eventually submitting to her physician, who prescribed bloodletting and blistering. The day she came home with a mercury douche, Robert finally intervened. “Perhaps it is enough for us to love each other, just as we are.”

He had been right, of course. Loving Robert was more than enough, and those last years before he died, when she abandoned all of the treatments and forced herself to embrace the life she had, as opposed to the life she wanted, were some of their happiest together.

Still, sometimes when Sally sees a family, like the one in front of her, she is filled with an anguish so intense it threatens to overwhelm her. She watches the governor ruffle the boy’s hair, sees the governor’s wife smile at the pair contentedly, and it is all she can do to remind herself that a child—even Robert’s child—would not have made his loss any easier to bear.

The House Is on Fire

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Women's Fiction

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1982186151

- ISBN-13: 9781982186159