Excerpt

Excerpt

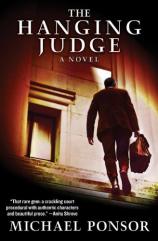

The Hanging Judge

Edgar “Peach” Delgado was down to his last three and a half minutes, though, of course, he didn’t know that. He strode out onto the front porch of his girlfriend’s house, grinning and pulling along a cluster of red, white, and blue helium balloons. Peals of female laughter and a small boy wearing striped pajama bottoms followed him out the door.

“With three sugars!” a woman’s voice called from inside.

The boy danced around, grabbing at the balloons and smiling up at Delgado worshipfully. Delgado bent to hand the trailing strings back to the child. “Go on and get yourself ready for school. I don’t care if it is your birthday. I’ll kick your butt.”

Delgado trotted down the steps and walked up to the corner of Walnut and High Streets. The Flats area of Holyoke, Massachusetts, was a beat-up part of town, but this autumn morning was so pretty even the dented trashcans and peeling storefronts looked prime. He swung his legs easily, feeling beneath his green Celtics jersey the .50 caliber Israeli Desert Eagle snug against his tailbone. He wouldn’t feel dressed without it.

Delgado was headed to the Cumberland Farms, where his cousin Joselito worked, to pick up some free coffee and saltines for his pregnant girlfriend, Carmella. It was the Tuesday after the Columbus Day weekend, and above him the October sky contained not a wisp of cloud.

Standing on the corner, Delgado rubbed his eyes and sniffed hard to clear his head. He’d been up late with connections down in Hartford, picking up half a brick to cook up into crack. He recalled with a twinge in his gut how during the negotiations some punk had stuck a pistol in his ear. People did useless shit like that all the time now. His own troops, the Walnut Street Posse, were under siege, and the safe parts of the Flats were getting tighter every day.

For maybe the twentieth time, Delgado decided he’d quit the street. This spring, he would be setting a grandson on his mother’s lap. He could lose the Eagle, stop hustling, and start acting like a proper dad. He glanced down the street at the Walnut Street Clinic, smiling to himself, remembering how crazy he’d gotten during Carmella’s last appointment there, tracing the shadow of his boy’s unit on the ultrasound and laughing like a fool.

Three houses down, Ginger Daley O’Connor, a pediatric nurse, maneuvered her minivan into a parking spot, uncharacteristically late for her volunteer shift at the clinic. As she exited the car, she tugged at the ends of her short, dark hair. She’d been rushed, and it was still damp.

Like Delgado, she was cheered by the sunny October morning, the best time of year in New England. The sawdust and gasoline smell of the Flats reminded her of the crowded apartment where she and her brothers had grown up. For all its grime and problems these days, she still loved to breathe the air of the old neighborhood.

When Ginger pulled open the slider to grab her yellow fleece, an avalanche of sports equipment, tangled helmets and shoulder pads, began tumbling out. She shoved the mess back in with her foot, slammed the door, and crossed the street, scowling. Twice she’d told the boys to get their hockey junk out of her car. Time for another little talk.

As Ginger approached the clinic’s entry, a brown-and-white beagle puppy tied to a parking meter wriggled happily toward her. She could not resist bending to give the precious thing a scratch behind the ears while it sniffed at the toes of her green Nikes. When she straightened up, she caught a glimpse of movement in the corner of her eye: an emerald-colored Celtics jersey in a splash of sunlight up by the Cumberland Farms store and a car slowing down.

Peach Delgado was about to step off the curb, then hesitated when he noticed a gray Nissan Stanza crawling through the intersection. A man who looked vaguely familiar threw him the Posse sign from the rear passenger window and called out.

“Yo, Peach, what’s up?”

Delgado did not respond right away. He was on the border of WSP territory, and he knew it was a common trick for gang enforcers to flash a rival’s sign. He stroked his mustache with his thumb and forefinger, considering. After a pause, he took another look up at the mild blue sky, decided it was too early for this kind of trouble, and halfheartedly flashed back, the three middle fingers of his left hand slapped downward on his thigh—an inverted W standing for the gang’s bywords, Loyalty, Duty, and Honor.

The Nissan’s rear window blew out in a clatter of gunfire, a smacking sound like a handful of marbles thrown against a chalkboard. Three bullets pierced Delgado: right thigh, stomach, and chest. There was no time even for fear.

Inside the Cumberland Farms, Joe Cárdenas, startled by the shots, stumbled around the counter into the doorway and saw his cousin Peach face-down in what looked like a spreading puddle of dark oil. One of his legs was twisted against the curb, and his right hand was stretched into the crosswalk as though he were grabbing for something. His body squirmed a little then shuddered into stillness. A hard voice inside the Nissan shouted, “Siempre La Bandera, motherfucker!” and the car took off, squealing around the corner.

The sound of the sharp cracks and breaking glass also brought the beagle’s owner, a neighborhood sixth grader, running to the clinic’s entrance. What she saw on the sidewalk was a middle-aged white lady trying to push herself up off the pavement with one hand, while she held on to her throat with the other. The lady’s eyes were wide-open, staring.

The girl dashed out to rescue her puppy, who was tangled around the meter and making deep red, clover-shaped paw prints on the concrete. Then she noticed the blood spurting like water from a hose through the lady’s fingers, pouring down the front of her yellow fleece and onto the concrete. The girl began screaming. Panicked spectators were crowding the sidewalk. Someone called 911, but it seemed like it was forever before anyone got there