Excerpt

Excerpt

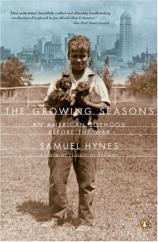

The Growing Seasons: An American Boyhood Before the War

Chapter One

The summer my father got married I lived on a farm. It wasn't his first marriage, of course, there was my mother, before. I was five when she died, but I remembered her, not as an everyday presence but in fragments of memory, in pictures and sounds and smells and touches. I remembered how she looked, not from a distance but up close, as a child in its mother's arms might see her: a small, soft body, a strong face with dark, sad eyes (on the right eyelid a small growth, a mole perhaps), thick chestnut hair coiled in a knot behind. I remembered her in the dining room of our house, ironing and singing a little song to herself while my brother and I lay on the carpet coloring in books, how she dipped her fingers in a shallow bowl of water to sprinkle a shirt, how the drops danced from her hand like blessings, catching the light from the window, and the warm smell of the iron and the steaming cloth. And I remembered lying warm against her in the back seat of our Ford as we drove home late at night-returning to Chicago from Rolling Prairie, perhaps-and how she sang to soothe me on the journey, songs from an old war, "Tenting Tonight" and "Just Before the Battle, Mother," melancholy songs, but comforting to a small boy because she sang them so quietly in the darkness and I, close to her, didn't hear her voice but felt it, a warm vibration through her breast as she held me.

One other memory. I enter a white room where she lies motionless on a white bed. Her face is pale under the bright hair, the eyes are circled by deep shadows. I approach the bed, but only the eyes turn toward me.

My father didn't talk much about my mother after she died, that wasn't his way, but occasionally a memory would escape his reticence. He told me once about a Christmas before the first war when she gave him a silver watch chain. He pulled the watch from his pocket and showed me the chain and the penknife at the end with his initials on it. "She saved up for it," he said with a kind of wonderment, "for a whole year." He carried that watch and chain until he was an old man, long after other men were wearing wristwatches, long after the silver initials had worn away. So I knew he loved her, though he never said so, not out loud.

There was also the photograph album, covered in dark green leatherette with black pages held in place by a cord. In it someone-my mother, I suppose-had mounted family photographs and written beneath them in white ink the names of the people and the places and dates. In one picture my mother stands by the front porch of a white frame house. Victorian gingerbread carving decorates the roofline, and roses climb on a trellis. She faces my father, who has his back to the camera. Her hands are on her hips, and her head is cocked quizzically, as though he has just asked her something-perhaps to marry him-and she hasn't decided what her answer will be, or has decided but won't tell him yet. In another picture they sit together in a field of tall grass. They are looking into each other's face, and smiling. That's what happiness looks like. Beneath the photograph the white ink inscription reads: "Just married. 1915."

A few remembered images and a couple of photographs don't amount to much, they don't compose a portrait or a life. But they were enough to leave a residue of tenderness in a child. It wasn't like not having had a mother at all.

My mother died in the first April of the Great Depression, in St. Paul, where Standard Oil had sent my father to work. A month later they fired him. Forty-two years old, grieving for his dead wife, out of work and out of money, and with two small boys to care for: what could a man do? What he did was go west, to Colorado, where he had heard there was work for him. He settled us first with a family in Julesberg, a little town in the sugar-beet fields near the Nebraska line, and then in a Ft. Collins boardinghouse, while he drove around the state trying to sell something on commission (oil, I suppose, that was what he knew). He must have failed as a salesman there; before the end of the next year we were traveling again, to Philadelphia, where his brother had a business, and had offered him a job. It must have been hard for my father to turn back east; generation after generation our family had always moved westward. That was what Americans did: west was opportunity, west was a new start. If you had gumption you went west.

The job in Philadelphia wasn't a real job; it was only my uncle being charitable. My father couldn't accept charity, not even from his own brother; he packed us up and drove again, south this time, to Fairhope, Alabama, a town on Mobile Bay where his sister, Elva, lived. He'd leave my brother and me with her while he looked for a real job.

My father didn't like to talk about himself much, but he told the story of his arrival in Fairhope many times: how he drove up the sandy street to Aunt Elva's house, how she was watching for him on the screen porch and ran out to the car, waving a yellow telegram and shouting "A job! A job! You've got a job in Moline, Illinois! You only have to get there!"

"I had five dollars in my pocket," my father said. "All the money I had in the world. I figured it would just buy enough gas to get to Moline. And it did. Now isn't that something?" And he'd fall silent, astonished at the one piece of real good luck he'd had in his whole life. Or maybe the one case of divine intervention. I don't think he distinguished between the two.

He left the next morning, and in the fall my brother and I joined him in Moline. It was our first journey on a train, and our first without our father. I wrote about it in a letter to my grandmother. And, I suppose because it was the first letter I ever wrote to her, she saved it. I was two weeks short of my eighth birthday.

The pretty-good place to live was another boardinghouse. We weren't there long; a few months later we moved to Minneapolis. Had he been fired again? Or offered a better job? Or simply transferred? I don't know. Adults know those things; but they don't tell children.

Later, when I traced our travels in those hard years on a map, I saw the pattern of my father's desperation: west and then all the way back east, south and then the whole way north, he had drawn his cross on the country. Seven moves in three years. No stop longer than a year. No steady, lasting job. Living in boardinghouses. Taking his family's charity. And always the two small boys.

But for me those were happy days. Julesberg: the plains lie flat and empty all around; the horizon is an exact and distant line. I sneak into a sugar-beet field with a gang of boys and steal sugar beets, and sit in the grass at the edge of the field and eat them with salt. One boy has a .22 rifle; we take turns shooting-at insulators on the telephone lines, at magpies. I aim at a cow far off in a field. The other boys say I'll never hit her that far away; she's probably in Nebraska. I fire and the cow jumps and lumbers off with her tail in the air. Ft. Collins: I ride a pinto pony up a mountain canyon, and drink clear water from a mountain stream, and wear a big hat and a bandanna around my neck. Philadelphia: in the bank above a stream in a vacant lot, neighborhood kids dig a cave, and we play robbers there, and hunt rats. Fairhope: the beach along the bay is endless, white, shadowed by pines; back in the bayous behind the town a rope hangs from a high branch of a water oak; I swing from it, out over the still black water, and drop into its coolness. Sometimes a cottonmouth swims past, ignoring me, minding his own business. Moline: in my school the fire escape is a hollow tube that you slide down when the fire bell rings; my father takes us across the river to Davenport to see a Fu Manchu movie in which Chinamen throw little hatchets at one another, and I am pleasurably frightened.

Even the hardships were lit with happiness. On the journey east from Ft. Collins a Great Plains blizzard swept down on us out of the north. Snow and sleet erased the world, day turned to night, and my father could keep driving only by following the taillight of a snowplow. My brother and I hugged together in the back seat of the Ford, wrapped in an Indian blanket, and sang songs-"Old MacDonald Had a Farm" and "Row Row Row Your Boat"-and my father made a joke. That was memorable because he never made jokes and couldn't remember the ones that other people told him. "We're the Rice Krispies boys," he said. "Chuck is Snap, Sam is Crackle, and I'm Pop!" It wasn't much of a joke-he'd made it up from the writing on a cereal box-but we laughed because it made us feel connected to his strength, and though the sleet rattled against the windows and the headlights showed only two cones of streaming snow, we knew we were all right. After a while we reached a town and spent the night. In the morning the sky was clear and the road was plowed.

My first remembered image of my father is from that journey. I see him from behind, from the backseat; he looms up in the darkness, tall, broad-shouldered, and steady, silhouetted against the light of the headlights reflected back from the falling snow, his big hands gripping the steering wheel, willing the car on through the drifts.

Other images come from the photograph album: my father in his first grown-up job, a seventeen-year-old powerhouse worker in overalls, standing before a panel of dials and fuses, with one hand on a brass switch handle, controlling power; and from his cowboy days in Wyoming, maybe twenty-one by then, standing beside his horse; and from his war, a brown studio portrait in a private's uniform, standing tall and straight and self-conscious. Images of strength, and of the kinds of work a strong man might be proud to do.

Still, strong though he was, my father must have felt considerable relief on his second wedding day, whatever else he felt; after those hard years he would have a home (in Minneapolis-we had moved again), and a wife to share his burdens, and his sons would have a woman to share in caring for them, someone they would call "mother." The woman he chose was an odd one, for him-an Irish-Catholic widow with three children. My father despised the Irish: there were only two kinds, he said, lace-curtain Irish and pig-in-the-parlor Irish, and both kinds were awful. And he hated Catholics. He was a Mason and a Protestant Republican; he had voted against Al Smith in 1928 because he believed that if Smith won he'd dig a tunnel from the White House to the Vatican. What was he doing marrying a woman who was both Irish and Catholic? He might get a home, but there would be crucifixes and bleeding hearts of Jesus hanging on the bedroom walls. He might shift the weight of his two children onto her shoulders, but he'd take on the heavier weight of her three. And worst of all, he'd have to submit to being married by a Catholic priest. Not in the church, he wasn't Catholic enough for that, but in some outbuilding of the church, furtively, in a corner.

It's not surprising that the photograph in the family album of the wedding party is not very cheerful. The new-made family huddles together on some Minneapolis street corner, perhaps outside the restaurant where we've just eaten the wedding breakfast. The bride stands at the center of the group, holding a bouquet of flowers. Sunlight is bright on her face; she squints at the camera through her thick glasses, not quite smiling-this is a solemn occasion-but looking as though she will, once the picture is taken. Her children stand protectively around her: her son, Bill, behind, her daughters, Rose Marie and Eileen, on either side. The girls wear steeply tilted white hats. One of them smiles.

My father, at the back, towers over the rest of us. His eyes are deeply shadowed and his mouth is set in a stern line. Chuck is on the right, wearing long pants (he's two years older than I am) and grinning optimistically. I'm on the other side, thumbs stuck in the pockets of my knickers. The look on my face says, "You'll never get me to smile, I've read 'Snow White' and 'Cinderella,' I know about stepmothers and stepsisters." Around us the life of the street goes indifferently on; a woman passes carrying a cake in a box, a man in a white cap ambles along the curb. They don't know that the group they are passing is not a family but two very different families gathered on a street corner almost, it seems, accidentally. Below the photograph my new stepmother has written the date: June 18, 1934.

Because my parents-no, that isn't right, my stepmother wasn't my parent; better call them, as we usually did, the folks. Because the folks were country people, it must have seemed right as well as convenient to send my brother and me to live on a farm while they went on their honeymoon and got used to being a middle-aged couple with five kids. My father knew of a farm out in the middle of the state, near Litchfield, that was worked by a childless couple; they would take us on for the summer if he promised that we'd do the kinds of work that farm boys our age did. My father must have thought that though one summer wouldn't make us country boys, it would give us something of what he felt when he remembered his own boyhood; and of course it would seem right to him that we should work for our keep.

All our journeys began in the morning dark, whatever the destination: "We'll make a good start," my father would say. In the kitchen in the half-light of dawn we whisper over a hasty breakfast (the rest of the family is asleep), while my father says impatiently, "Shake a leg! Shake a leg!" opening the back door quietly ("Don't let the screen door slam"), and the garage doors, and backing (quietly, the car's engine whispering, too) into the empty street. The houses along the block are dark, except here and there a kitchen window lit-a wife whose husband is on the early shift is making breakfast, or an upstairs window, the bathroom probably-some working man shaving.

Our route is west along West Thirty-fifth Street into the night's last darkness, and north on Lyndale. At that time of earliest morning the traffic lights are still switched to amber, and make patches of yellow light on the shadowy street. There are no other cars moving, and no walkers on the sidewalks. The air is still cool, but as the sun rises and the eastern sky turns gold and then flame-colored, my father says, as he always does on hot summer mornings, "It's going to be a scorcher!"

U.S. Highway 12 runs due west from Minneapolis to Litchfield. But it doesn't stop there, my father says; it goes straight on to South Dakota, up into North Dakota, through Montana and Idaho, and clear across Washington State to the Pacific Ocean. Right across the whole Northwest Territory-that's what they called it before there were states. Folks still call these parts the Northwest; you see it in the papers.

I imagine that line on the globe at school, running on and on through the Northwest Territory, right over the horizon, over the curve of the world to the blue end of the land, and dropping into the ocean with a plop.

Beyond the city suburbs and the cottages around Lake Minnetonka the farms begin, and my father becomes a country man. The corn looks good, he says. Knee-high by the Fourth, folks say; a good crop should be knee-high by the Fourth. He means the Fourth of July. Birds circle above a wood and he says: Hawks. Must be a dead animal in there. He holds the steering wheel as though the car were a plow and drives it on into the summer morning.

Out here the sky seems wider, but not higher; in Minnesota a summer sky is like a blue enormous plate, and the clouds that float on it ("fair-weather cumulus," my father calls them) seem close to the earth and friendly, like sheep drifting in a flock. As the sun rises in the sky heat waves begin to shimmer on the road ahead, blurring the outlines of things, and mirage pools lie like water on the blacktop. My father breathes deeply of the country air and rolls up his shirtsleeves.

Along the roadside the usual furniture of country highways: solitary mailboxes on posts at the ends of rutted roads; telegraph poles marking the line of railroad tracks; crisscross warning signs where the tracks cross a road. Little signboards set on posts recite Burma-Shave rhymes, one line to a sign. My brother and I chant them as we pass: PITY ALL / THE MIGHTY CAESARS / HAD TO PULL THEM / OUT WITH TWEEZERS, AND HE'S UNHAPPY / IN THE GRAVE / HE CANNOT GET / HIS BURMA-SHAVE. On the ends of barns advertisements covering the entire wall urge us to Chew Bull Durham and Visit Rock City. A sign at the edge of a town announces TOURIST CABINS and we can see them, back from the road in a grove of trees, a row of little sheds no bigger than a double bed ("like privies," my father says), lonely, shabby, and unwelcoming. A big house on the main street has a shy, embarrassed notice on its broad lawn: TOURIST ROOMS-some widow trying to get through age and hard times by renting her spare rooms. But there are no tourists.

Halfway along our journey we approach Waverly. Long before the town itself comes in sight I can see the twin spires of its church rising tall above the level farmland. "Catholics," my father says. "They always build their church on the highest hill in town." Certainly they have done that in Waverly: the vast church sits stranded on its height, like Noah's Ark on Ararat, looking down on the nothing much that is the town-a few houses, a store with a gas pump. My father seems pleased that the town has not grown and prospered around the church; this time the Catholics got it wrong.

Excerpted from The Growing Seasons © Copyright 2004 by Samuel Hynes. Reprinted with permission by Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. All rights reserved.

The Growing Seasons: An American Boyhood Before the War

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Penguin (Non-Classics)

- ISBN-10: 0142003964

- ISBN-13: 9780142003961