Excerpt

Excerpt

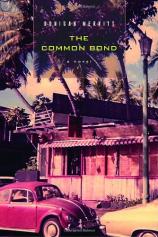

The Common Bond

Chapter Two

Earlier that day, the Aloha Airlines plane he had taken home descended beneath thick, pearl-colored volcanic haze and settled fast over a coral reef where blue water broke white before fanning out pacified and green into the lagoon. The flowered airliner passed low over the shoreline, chasing its crinkled indistinct shadow across the rumpled field of laupahoehoe lava surrounding the Kona airport; lava as dried out and hard as an old chocolate cake, kiawe trees clinging to the crust as brown and dead as tumbleweed.

Morgan searched for the high green mountain slope while the plane taxied toward the open-air terminal, but it was only visible in outline through the strange and extraordinary haze.

When the door opened for the ramp, a heady warm perfume meandered through the cabin --- gardenia, plumeria, ginger, a strong overlay of kerosene. Passengers descended into a diffused but still radiant sunlight to the accompaniment of drums and steel guitars, playing tropical Muzak. A trio of lei girls in skirts of plastic grass and bras of plastic coconut shells waited for a tour group. Two round-bellied taxi drivers in Aloha shirts hovered near the baggage carousel drinking Cokes in cans. By the gate, a young Japanese woman held up a clipboard sign and a rainbow-striped umbrella.

Morgan descended the ramp behind a Japanese man in a white terrycloth hat and white short-sleeve business shirt. As they moved toward the exit gate, the man’s wife walked backwards step by cautious step to capture her husband’s arrival on a minicam.

Morgan found a taxi and threw his bag into the back seat. Right away the driver wanted to tell him that the haze came from the ongoing eruption of Kilauea. “We call it Vog. Means volcanic fog.”

“How long this time?”

“The eruption? Off and on forever. This one, a couple months.”

They turned out onto the road toward Kailua town.

“It’s killing tourism.”

Morgan wondered if that might be a mixed blessing.

“Yeah,” the driver laughed. “Careful what you pray for, right, brah?”

As the taxi neared Kailua, he could discern the softly rising, thickly vegetated slope of Hualalai mountain.

Before Victoria, he was a fisherman. His house was up there on the lower slopes of Hualalai, the cloud-shrouded purple and green mountain backdrop to the village of Kailua-Kona. It was a small house, really a shack, unpainted and constructed single-wall, with piles of books and stacks of paper holding his own ambitious stories, all of it being curled by humidity and gnawed on by bugs. The tin roof leaked and tangled vines threatened to sneak in through the koa wood flooring. Originally the house was used by seasonal coffee pickers. It sat well back from the main road, along a rain-rutted trail through a jungle of such massive tropical profusion that the house materialized from the background like a phenomenological trick. Electricity came into the house from a single drooping feeder line that ran up from the main road in an arc like the slope of an old horse’s back. There was no water piped up from the town below. Rain captured in a cistern was diverted to the house via a gravity-fed pipe. The toilet had its own tiny shed in Nature. It was about a mile and a half to the bay where the sport fishing boat Dolphin moored; he walked down to work in the mornings at sunrise, which doesn’t vary much at that low latitude. He was habitual, always eating breakfast at the Seaview Café, which had no glass in windows with panoramic views over the sea wall and harbor and out over the omnipresent Pacific. He ate heavily, fresh papaya halved in a koa bowl and doused with lime juice, fresh pineapple chunks on cottage cheese, fat round soft pancakes with strips of bacon crisscrossed on top and smothered with papaya syrup, two cups of black Kona coffee, and a sixteen-ounce mason jar filled with ice water. He would not eat again during the day as they trolled offshore ledges for Pacific blue marlin, yellowfin tuna, Hawaiian mackerel, and dolphin fish, except for an apple and some soda crackers. He would go through two quarts of water to keep hydrated against the clutching heat of the tropical sun. At night, it was usually sunset by the time Tioni and he had cleaned the boat and put away the gear, Morgan would get a grilled ahi sandwich or a fat hamburger at the Red Pants, a bamboo, tin-roofed bar directly across Alii Drive from the sea wall. He would stay to drink a few beers with other Kona fishermen. It was their bar. They told hours of lies, shot nine-ball, hustled the few brave female tourists who wandered in, and sometimes had painful but unimportant fistfights. Years ago, when Morgan was a boy in grade school, actors went slumming there; Richard Boone and Lee Marvin kept fishing boats in the harbor. Then Morgan would hike back up to his house and write page after page describing what he had seen, had heard, and could imagine. These stories he never showed to anyone, not even Tioni.

Morgan believed that those days were lived on the verge of being the perfect life.

The taxi let him off at the Sunset Lanai, a motel on the southern fringe of Kailua town, across the road from a small cove at the edge of the harbor. The single-level, rectangular motel with a veneer of black lava rocks covered with red bougainvillea and yellow hibiscus was shaded by tall, curving coconut palms, ohia and kukui trees dropping their black nuts all over the property. It was hardly visible from the road. The only sign pointed to the café behind the motel, a café with open walls and a palm thatched roof where mourning doves nested.

It was not the kind of place appealing to persons wanting a lounge with a floor show, a Polynesian revue with dancing girls, tom-toms, flaming batons, slick songs, and sweet mai tais. You never saw there banzai-marching Japanese in matching aloha clothes and porkpie hats, tagged like children traveling alone. The Sunset Lanai was not on the lists of mainland booking agents. It had ten rooms, each with yellow-painted cinder block walls, a tin stall shower, and simple, cheap wicker furniture. The rooms were seldom all taken.

But from those rooms one could hear the wind-rippled sea washing over the black rocks in the cove across the road, the trade wind breathing through the trees, the clicking of geckos prowling for supper, the soft and beautiful mourning doves on the café roof. The air smelled salt clean, pungent with exotic flora, lacking the intemperate, disgraceful noises and odors of tourism, from which the town had lately fed.

Locals went there to fuck in secret or to eat fine papaya pancakes in the café.

It was to honor a memory that he returned there, where a decade ago he first spent the night with Victoria.

***

Eight o’clock. He had a dreadful headache behind his eyes. He’d been trying to sleep but had only lain naked and sweating atop the sheet, nursing the inevitable treacherous passage of airline frou-frou drinks through his body.

Open jalousie slat windows filled much of the wall opposite the narrow bed and a palpable, embracing air invaded the room. Through the windows he could see the deep purple sky, the island rolling away from the sun. He dozed for a while before awakening to a mosquito’s whine. He reached back and turned on the rotating fan affixed to the wall above the bed. Faintly, he heard music from the café, then slept again, until the sting of stomach acid in his throat awakened him. He was dreaming of pretty brown-bellied girls, their bellies made for bouncing.

In the shower, facing the hard, sweet spray, letting the water churn and bubble from his mouth like rising from a deep pool, he scrubbed hard, but apparently it took more than motel soap to wash away grief and guilt.

He felt swollen.

Sometimes, especially in bed while trying to fall asleep, he had the distinct feeling of expanding, swelling, becoming heavier, sinking into the mattress, being swallowed, suffocating. He knew it for a phantom, like the occasional pain behind the ugly, ragged scars on his right leg, the pain that really wasn’t there any more, pain that remained only distinct as an aspect of memory. Was it real if he felt it? Was it not real because it was a phantom?

He didn’t remember packing. He didn’t remember going to the airport and buying the ticket that brought him back to the island. He was drunk. The contents of his duffel bag were like surprise gifts when he emptied it onto the bed: Four pairs of shorts, six T-shirts, a pair of flip-flops, a pair of jeans, a black windbreaker, a toiletries bag; no socks and no shirts, except for the things he wore on the plane, which now lay on the floor scattered between the bed and the bathroom. He brought two credit cards and three-hundred-forty dollars in cash.

He had run out of whiskey. Alcohol was pain’s only refuge, the only means he had for delineating the eye of the hurricane, for becoming calm, for finding the inside of that small circle of self-protection there might be amid the whirling, precarious storm of guilt he could not penetrate.

He pulled on a pair of shorts and a T-shirt before heading out to find a drink, but the walk to the road proved he wouldn’t be able to do that tonight. His knees suddenly rested and he settled toward the sidewalk like a leaf, before catching himself and lurching into a pretense of erectness. It happened now and then, knees went on a sort of coffee break, fingers let go of their own accord, vision came and went, the sidewalk rose to meet him on the way down. But, then, he really hadn’t been a blind, stinking, fucking drunk long enough to get used to the surprise of its distinct attributes. He could still embarrass himself and went back to his room hoping he might sleep.

There were only the memories now, the dreams. He fell asleep remembering the first time he was here with the beautiful and mad woman who would become his wife.

Excerpted from The Common Bond © Copyright 2012 by Donigan Merritt. Reprinted with permission by Other Press. All rights reserved.

The Common Bond

- paperback: 392 pages

- Publisher: Other Press

- ISBN-10: 1590513061

- ISBN-13: 9781590513064