Excerpt

Excerpt

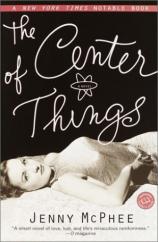

The Center of Things

1

TIME

"Most of life is wasted time." —john berryman

"I read poetry to save time." —marilyn monroe

"The distinction between past, present and future is only an illusion, even if a stubborn one." —albert einstein

Marie was early. And when Marie was early, she agonized. During the first five minutes, she simply couldn't believe the fact that she was early yet again. Then she began hating herself. It started with hating herself for being early, but she soon moved on to hating herself for having dropped out of graduate school, for not being married, for being partially deaf in one ear, for writing for a tabloid, for being already thirty-nine years old, for having straight hair, for not having children, for never finishing the philosophy of science paper she had been working on for nearly fifteen years, for being five feet eleven and three-quarters inches tall. When Marie could no longer bear her checklist of miseries, she started calculating the number of hours, to date, she had wasted by being early, and, based on those numbers and her life expectancy, how many more she would waste in the future.

According to Marco, hers was an uncommon case of reaction formation to the very common fear of abandonment. He had explained to her that most people react to the fear of abandonment associated with time appointments by being late themselves. Or they counter the fear by being compulsively on time. "But you, Marie," he had said, "anticipate the fear, as if by creating the same conditions earlier in time you can cancel out what you expect to occur later on. It is beautifully symmetrical, perfectly logical."

It seemed grossly illogical to Marie, who continued to add up the hours of her wasted life on a bar napkin at the Ear Inn. She worked as a researcher and reporter for the Gotham City Star, Manhattan's only remaining evening tabloid, and one of her duties for the paper was to gather material for the advancer file, which contained the obituaries of people not yet dead. She had come to the bar in a similar capacity—but this time she would also be writing the story herself. Marco called her obituary work a kind of literary pre-necrophilia and a prime example of her neurotic need to anticipate abandonment.

Just the day before, Nora Mars, the 1960s glamour queen and actress, had suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage and was in a coma. Despite her relative youth—she was sixty-two—and her otherwise excellent health, she was by all medical accounts unlikely to recover. News of the tragedy had devastated Marie. Since Marie was about ten years old, Nora Mars had been her most revered idol.

Nora Mars was the girl next door gone awry, in both looks and attitude—she had white-blond hair and a peaches-and-cream complexion, but her slanted green eyes made her look like some exotic hybrid. ("My mother passed over the postman for the Chinese laundryman," she had once notoriously told the press.) Her atypical beauty and hard-edged innocence combined to form Marie's teenage idea of female perfection.

Growing up, Marie had fantasized about being any number of movie stars she had come to know by watching endless hours of late night television. Before her parents were divorced, when she was eight, television had been allowed for only one hour on Saturday mornings. But after her father left, her mother stopped caring so much about rules, and Marie, over the following years, more than made up for her early childhood deprivation. The television set was on from the time she got home from school until she left again the next morning. She was a devotee of The 4 O'Clock Movie, The Million Dollar Movie, Movie Playhouse, Late Nite at the Movies, and The Late Late Late Movie. By high school she had few friends and rarely went out except to the movies, accompanied by her younger brother, Michael.

With Michael as her interlocutor, she honed her tastes. She thought Katharine Hepburn overzealous and Doris Day whined too much; she preferred Gene Kelly to Fred Astaire but couldn't resist Easter Parade. She swooned over the soft-spoken Gary Cooper, adored the bumbling Jimmy Stewart, and wanted to marry the boisterous and charming Cary Grant.

In the end, however, the movies Marie came to love above all others were the noirs starring small shifty men—the kind you shouldn't marry—like Humphrey Bogart, George Raft, Peter Lorre, Alan Ladd, and James Cagney. As for the women, she worshipped the femmes fatales played by actresses such as Hedy Lamarr, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Lauren Bacall, Barbara Stanwyck, Rita Hayworth, Ava Gardner, Gloria Graham, Gene Tierney, and Veronica Lake. But if she could have chosen to look and act like anyone in the world, it would have been Nora Mars.

Nora Mars did bad things and bad things happened to her both in real life and in her movies, and even so she always came out ahead. Sometimes, with all her husbands and scandals, she seemed to be on a mission to outrage and shock the public. But then she would make some comment or say some line, and the tangled truth of it would be so surprising that Marie, along with most of the country, just loved her even more. Nora Mars, Marie concluded, was a complete contradiction. While she needed to be loved by everybody, she did everything she could to make them hate her. She was a conformist who refused to conform, and her deep vulnerability was her greatest strength.

Over time, Marie and Michael began to write down and then memorize lines of movie dialogue they particularly liked, and during the two years they overlapped in high school, whenever they crossed paths in the halls, they would quote one-liners at each other and see who could name the title, actor, and date of the movie first.

("For all I know, eternity could be time on an ego trip." Nora Mars, The Reckoning, 1959.)

Marie still played the game with herself sometimes, but it inevitably made her think of Michael, who had moved to L.A. fifteen years earlier and hadn't spoken to her since. He was the only person on earth who would be able to hear that Nora Mars line and understand precisely how Marie was feeling in that moment, as she sat in a bar obsessing about time wasted, time lost, time yet to be spent, as she waited to interview Nora Mars' third husband out of five—Rex Mars. (A renowned stipulation in Nora Mars' standard prenuptial agreement was that her husbands had to take her name and keep it even in the eventuality of divorce.) On Marie's napkin, the figures showed that so far she had wasted 10,264 hours of her life waiting.

Excerpted from The Center of Things © Copyright 2001 by Jenny McPhee. Reprinted with permission by Ballantine Books. All rights reserved.

The Center of Things

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345447654

- ISBN-13: 9780345447654