Reading Group Guide

Discussion Questions

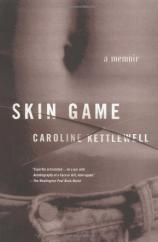

Skin Game

1. An increasing number of intimate memoirs—many on “taboo” or disturbing topics—have appeared in recent years. Proponents argue that literary memoirs can serve as a powerful means of discussing universal themes through personal experience. Critics dub the genre “confessional” and deride it as symptomatic of a society caught up in uncritical self-absorption. Do you believe there are subjects too personal to put in a book? What is the value of using literary writing to explore highly personal experiences?

2. Kettlewell writes, in Chapter 11, “There’s probably no critical mass beyond which cutting yourself would ever seem, to most people, like a reasonable choice.” Does she suggest that she believed cutting was a reasonable choice? Could self-injury be argued to be a rational behavior? Does the author suggest it is?

3. Tattooing, body piercing, and even scarification and branding, have become fashionable lately. What is the difference between such body injury in the name of fashion, personal expression, or group identity, and Kettlewell’s self-injury? Is there a difference? If Kettlewell’s self-injury is deemed “dysfunctional” by mental health experts, should tattooing or other body alteration be thought of in the same way? What about elective plastic surgery?

4. “So when I discovered the razor blade, if you’ll believe me, cutting was my gesture of hope,” says Kettlewell. In what way did cutting serve as a “gesture of hope” for the author? Does the author ultimately view self-injury as self-destructive or beneficial? Or is her verdict more ambivalent?

5. “Anorexia is not for the weak,” the author writes in Chapter 17. Why does starving herself make Kettlewell feel strong? Does our culture place too much value on “self-control”? Many cultural critics have noted that the standard of female slenderness grows more stringent every year, with everyone from movie stars to Miss America contestants markedly thinner today than they were 20 years ago. What do you think “thin” stands for in our society? Why is it so valued?

6. The narrative tone, the “voice” of the book, is often cool, ironic, even humorous—even in the midst of disturbing and unsettling scenes. What impression does the tone serve to give you of the narrator? Does the voice heighten or mute the intensity of the cutting scenes?

7. The author never defines a particular “cause” for her history of self-injury, but rather argues that “some things are too complex to suffer reduction to a simple equation of why/because.” Do you feel that the book serves as a satisfactory explanation of why the author became a cutter? Do you think the book needs to offer a satisfactory explanation?

8. Kettlewell writes, “Here’s the part where I’m supposed to have the big epiphany: some climactic confrontation, a couple of weepy scenes, and then the tidy wrap-up, the denouement.” A number of recent memoirs express an ironic self-awareness of the “conventions” of memoir—in Kettlewell’s case the conventions of a “recovery” memoir. As you read the book, did you expect the author to overcome self-injury by the end? Would your response to the book have been different if she hadn’t? Does a memoir such as Kettlewell’s have to end on a positive or redeeming note?

9. “Maybe…you have to make your journey and bear its scars,” Kettlewell argues. Is Kettlewell suggesting that there was value in her experience with self-injury? If you could live your own life over again, are there painful incidents you would willingly relive, or would you choose to avoid them? Scientific advances hold out the promise of “curing” emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety. Can you imagine any reasons why a person might choose not to be “cured”?

10. Kettlewell notes at several points in her book that, despite her confused and turmoiled mental state, from all external appearances she led a “normal” life. Based on the story she tells, would you agree with her conclusion? If, as in Kettlewell’s experience, only one aspect of a person’s behavior is notably “disturbed,” would it be correct to call that person mentally ill? Do you believe that emotional disorders are caused by experience, biology, or both?

11. “Memory is faithless like a cheating lover, telling you what you believe is true,” Kettlewell writes. How reliable is memory? What is the difference between memoir and biography? Between memoir and literary journalism? Since two different people might have completely different memories of the same event, what defines “truth” in a memoir? Imagine how the “interrogation” scene in Chapter 2 might be different if written by one of the teachers present.

12. “We all inevitably present a version of ourselves that is a collection of half-truths and exclusions,” Kettlewell writes at the end of Chapter 16. Do you believe that is true? Are there thoughts you’ve had or facts about yourself that you would never reveal to anyone? Is it ever possible to be completely honest?

Skin Game

- Publication Date: June 7, 2000

- Paperback: 192 pages

- Publisher: St. Martin's Griffin

- ISBN-10: 0312263937

- ISBN-13: 9780312263935