Excerpt

Excerpt

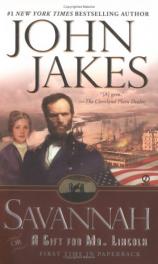

Savannah: Or a Gift for Mr. Lincoln

PREFACE

Between the burning of Atlanta in November 1864 and the burning of Columbia in February 1865, there occurred one of the most remarkable yuletides in American history.

Late in November, William Tecumseh Sherman, nemesis of the Confederacy, launched out from Atlanta in a campaign still written about in books and studied in military colleges. He cut his lines of communication, literally disappeared off the Union's war map and, with his army of sixty thousand, marched across Georgia to the Atlantic.

It was a march rife with pillage and arson, civilian suffering and martial excess. Sherman professed a hope of shortening the war by "making Georgia howl." Those caught in his path called him the new Attila.

Yet when the Yankees reached the sea in December, a curious interlude followed. Sherman captured and occupied Savannah and remained there throughout the holidays. It was a Christmas like none that had ever been and none that ever would be: not quite war but not quite peace, forever remembered by those who lived it and those who came after.

Through the eyes of a few --- Yankees and Confederates, men and women, and one special girl --- this narrative spins a tale of that Christmas.

Thanksgiving Afternoon, 1864

Little Ogeechee River

Thanksgiving was a holiday not much observed in the failing Confederacy. It was suspiciously Northern in origin, but more important, Abe Lincoln had lately promoted it to boost home-front morale. Anyway, there was precious little to be thankful for. The air was biting. Last night it snowed, although the white dusting melted away by noon. The tidal waters had a flat, cold sheen; thick windrows of spartina grass on the islands dotting the marshes had lost their summertime brilliance. The worst was unseen: Somewhere out beyond the autumnal forests and farmsteads was the trampler, the looter, Sherman.

Two youngsters, together with a starving pig named Amelia, whiled away the afternoon beneath a straggle of sable palms on the bank of the Little Ogeechee, just where the Grove River flowed in from upstream. Neither youngster came from a poor family, but you wouldn't have known it, given the patched and threadbare state of their clothes.

"You having anything good for dinner?" asked the boy, Legrand Parmenter. He was fourteen but looked older because of his bony height and craggy jaw.

The girl, twelve, pulled her patched shawl more tightly around her shoulders. The girl's name was Harriet Lester; all in the neighborhood, including her companion, knew her as Hattie. She was approaching the doorstep of womanhood but was not quite there yet.

"Same as yesterday," she said. "Blue crabs I caught this morning with mullet heads. Mama's boiling them. I have to pick the crabmeat before we can eat."

"Don't act so peeved about it. You're lucky. We get possum."

A silence. Food was a prickly subject. After the hateful Union general drove the citizens of Atlanta out of their fair city early in November, then torched it, conditions along the seacoast had deteriorated to previously unimaginable depths. Railroads no longer ran. A few provision schooners sneaked down the Savannah or the Ogeechee, but what little they carried was fought over by mobs in the city's public market. Hattie and her mother, Sara, were never in town to get any of it.

In front of Hattie and Legrand, the river curved prettily through rice lands long ago cleared of tupelo and pine and palmetto. Behind the children lay square fields where generations of Lesters had dug out stumps, burned brush, built dikes and trunks; a house; and a rice barn. Hattie's great-grandfather had named the place Silverglass late one afternoon at candle-lighting, when the confluence of the Grove and Little Ogeechee shimmered and shone like enchanted metal. The county seat, the charming old city of Savannah, lay roughly ten miles northeast.

The boy seemed to have that place on his mind: "Beauregard's put a new general in charge of city defenses. Hardee." Legrand seemed to be dancing around something important but so far hadn't said it outright. He'd been nervous and fidgety ever since he came calling. He'd get to it --- maybe.

"Old Reliable." Hattie pulled a face. "Mama says he can't be too reliable --- he's only scraped up ten thousand troops, and the Yankees are coming with six times as many."

She studied a limp white ribbon tied to the tail of her beloved Amelia, a young sow, rust red. Amelia's dwindling weight created a deep anxiety in Hattie. She frowned and drummed her peculiar shoes on the hull of the overturned rice boat where she sat. The shoes consisted of strips of canvas attached to thin soles of poplar. A pair cost thirty cents in town, made thunderous noise on pine floors, and were FULLY GUARANTEED TO LAST UNTIL VICTORY IS OURS. Leather shoes, like so many familiar things, had gone to the soldiers at the front.

Legrand continued to ponder and fidget. Hattie jumped off the rotting boat and poked at Amelia's ribs. "Oh, damnation."

Legrand Parmenter's eyes bugged. "Are you allowed to say words like that?"

Hattie tossed her thick yellow curls and flashed her periwinkle-blue eyes. "I guess I can if I do, Legrand. Everything's topsy-turvy."

She explored Amelia's ribs again. The pig rebelled, snorted, and ran off. A green heron stepped through the reeds below the bank, then lunged and speared a fish.

Legrand said, "The birds around here are better fed than people."

"Or pigs. Amelia can't eat acorns and snakes forever. She'll starve to death 'less we find some food."

Legrand eyed the western horizon, a vista of lemon-colored marsh and sky tinted by the pale sun. "If General Sherman's boys don't kill us first."

Hattie showed her fist. "If I lay eyes on General William Tecumseh 'T-for-Terrible' Sherman, I'll give him a sockdologer, see if I don't."

Legrand couldn't help laughing. "Oh, you're going to punch him, are you?"

"Do worse if I could. Night before last, I dreamed I captured a dozen of those blue-bellies. I knew a magic spell to change them into eggs. I climbed all the way to the roof and dropped them off one by one."

"Phew. You're a da --- er --- blasted little rebel, all right."

"Well, I should hope so." Hattie's expression changed to one of pensive melancholy. "Pa died for Georgia, even though he never went into battle."

Legrand inched over to stand beside her, although he wouldn't risk slipping his arm around her; she inspired a combination of adoration and wild terror. In the bulrushes bordering a man-made canal on the other side of the river, a marsh hen sang. The vast Atlantic, some ten miles east, filled the air with the unromantic but familiar scent of salt and tidal mud. Legrand said, "Did I tell you James ran off Monday?"

"Your patroon?" The old term meant "boatman," a slave usually considered the most important on a rice plantation.

"Uh-huh. Guess it doesn't matter much --- our barge is wrecked, like yours, and there's no crop to float to market. James promised to cut us a pine tree for Christmas, confound him."

"Do you have any colored folks left?"

"No."

"We don't either," she said. "I found our Sam and Cora camped not a mile up the Grove Road. They were nice and polite, but little Braxton stuck out his tongue at me, and Sam said I couldn't order them back home --- jubilee's come and they didn't belong to us anymore."

"That's all you hear: jubilee," Legrand agreed.

"Pa depended on his nigras, but he was always nervous about it. He told me once that when Governor Oglethorpe started the colony, way back, he made slavery against the law. Didn't last long --- people here wanted to be like the fancy South Carolinians."

"The ones who got us into this fix." Another hesitation. "Do you know something?"

"Legrand, don't be annoying. I know lots of things. What is it you've been busting to say all afternoon?"

He looked very stiff and important. "Mayor Arnold is writing up a proclamation. First of the week, he'll ask all able- bodied men to rally to defend Savannah."

"Who told you?"

"Mr. Sappington."

"Why, he's a hundred and ten years old. He couldn't defend anybody."

"You're wrong. He's half that age --- plenty young enough to serve."

"Then hurrah, we can't have school without the teacher." Hattie lifted her skirt an inch and did a quick dance in her odd shoes. "What's it got to do with you, Legrand? You're not an able-bodied man --- you're a boy."

Legrand flung a stick into the river where it skipped once, then floated peacefully, turning and turning on the outgoing tide.

Hattie retrenched: "I made you huffy."

"Yes, you did. I'm as able as the next body --- a lot more fit than those old grandpas who march around the squares in town with canes and broomsticks instead of guns. People take me for sixteen --- seventeen sometimes." He jammed his big-knuckled hands on his narrow hips. "When the call comes, I'm going."

"To war?"

"Well, I don't mean to some cave."

"That's what you came to tell me?"

"It is. If we have to defend our land with our blood, we will," he declared with a sententiousness that went right over Hattie's head because she was envisioning a red blossom on Legrand's shirt as he sank and expired with a Yankee ball piercing his heart.

She wanted to sob; she didn't, because she hated bawl-babies. She wanted to throw her arms around him, but it wasn't seemly for a girl to do that, no matter how flushed and dizzied with patriotic passion. Poor, dear Legrand --- he was a mere male, but he was also her special friend.

Barely whispering, she said, "How soon will you go?"

"Any day now. Before Christmas, for sure. Nobody knows how soon Sherman will get here, or if he will. Nobody knows where he is until he arrives, and then people can only guess where he's going next. My pa says there's never been such a crazy march --- poling off from Atlanta, telegraphs cut, even Old Abe and those other Washington monkeys" --- he bellowed in a fair imitation of a great ape --- "they don't know where he is until and unless he announces himself with artillery and cavalry."

Hattie shivered, and not from the cold this time. Though she and her mother regularly worshiped at a little Congregational chapel nearby, Hattie felt she wasn't on the best of terms with the Almighty. She must rectify that for Legrand's sake.

A bell clang-clanged. Hattie said, "Time to pick the crabs." Amelia had settled herself belly-deep in the sand and appeared to be sleeping. Hattie poked her. The porker reluctantly heaved to all fours, awaiting further instruction.

"You're welcome to stay and share some, Legrand."

"No, I have to go on home, but thanks."

"I think you're very brave."

He preened and puffed up considerably. Hattie scratched Amelia's head, then pointed off across the weedy rice squares to the distant house. All the trunks in the rice dikes had been closed after the fields were drained for lack of hands to tend a crop. The wind felt stronger, sharper.

Impulsively, Hattie grasped her friend's hand. "We can't win, can we, Legrand?"

"I don't think so," Legrand answered, the contact of hands reddening him. "I think there are too many Yankees. But we can put up a devil of a fight before they drive us down."

All at once Hattie remembered Christmas. In the course of the last four years she'd experienced diminishing expectations for the increasingly popular holiday, but this one promised to be the worst. Sherman was coming. And Legrand was going off to fight him.

Silverglass Plantation

The children and the pig walked the checkerboard of rice dikes toward the plantation house. At one point a dike had collapsed. Legrand easily jumped the gap, but Amelia balked and retreated. Hattie rolled her eyes, picked up the pig, and leaped.

She teetered on the far edge; dirt cascaded into the gap from under her wooden soles. Amelia wriggled out of her arms and ran squealing toward the run-down dwelling half concealed by tall magnolias. Hattie's father had planted those trees but hadn't lived to see them mature to their current magnificence.

Hattie's parents, Ladson and Sara, never fooled themselves into thinking they stood on the top rung of the social ladder, but neither were they dour-faced crackers who raised peanuts in the hinterlands and came to Savannah only to shop and truculently crack the whips that lent them their name. The Lesters, from Liverpool originally, were a long time in Georgia; nearly a hundred years. They were respected and, before the war, prosperous.

Ladson Lester was a planter who never stinted on physical labor and who kept neat books when he wasn't indulging his one fatal vice: consumption of beers, ales, wines, and spiritous liquors. Long-suffering Sara loved him and tried to save him. She took him to church every Sunday and to temperance meetings and tent revivals put on by itinerant preachers. He would swear he'd conquered his demon and would remain pure and clear-eyed for several weeks, but then he'd sneak away and enjoy one of his "bracers," as he called them, and he'd be off on another tear.

All the Lester men, Ladson included, were considered strong-willed, assertive in one way or another. People claimed this was because Liverpudlians were cheeky, like Parisians or Berliners. Whether the trait traveled down five generations, and across sexes, is debatable, but there was no doubt that Hattie Lester had a quick tongue and a forward manner. Stiff-necked individuals who disliked those qualities in a girl called her saucy, unfit for proper society.

Georgia at the outbreak of the War for Southern Independence was a conflicted place. Yes, she was stoutly Confederate and sent her men to fight and bleed for the cause, whether it was preservation of slavery or the right of secession or both. (More than 140 years later, this issue is still debated.)

Yet Georgia's fires of rebellion never burned quite so hot as those in neighboring South Carolina. Georgia had a streak of Unionism, sometimes deeply buried in the bosoms of her English and Irish and Scots and German settlers. Ladson Lester, for example, doubted the wisdom of splitting America in two, and he harbored a heavy guilt from owning other human beings. This in no way softened his patriotism or reduced his willingness to serve. In the summer of 1861, he joined a local regiment, the Yamacraw Mounted Rifles, presumably destined for glory on distant, and as yet unknown, fields of battle.

Each man had to furnish his horse and gun. Ladson bought his horse from a neighbor known for sharp dealing. Ladson didn't have a good seat; on the third day of drill, he felt compelled to improve his confidence with a generous bourbon bracer. The horse threw him and broke his neck. He died before Sara could reach the drill field. A story went around that the neighbor said Lester should have known better than to buy a horse named Old Bucky.

After Ladson's death, Hattie and her widowed mother continued to live in the house built by Ladson's father, slaves, and Ladson himself when he was eight years old. Sara Lester strove to keep the plantation going, but she lacked her husband's talent for organization and attention to detail. She hired an overseer who proved to be a thief. He lasted just eight months. She worked in the flooded fields herself, only to fall ill and nearly die of a miasmic fever.

Disaster piled on wartime disaster. Sherman's feared army of Westerners rampaged into Georgia from Tennessee, overcame and destroyed Atlanta, and then turned east. The effects were sharply felt at Silverglass. The slaves grew pertinacious. They slipped away by ones and twos until Hattie and her mother were alone except for Amelia, whom they couldn't bring themselves to barbecue to satisfy their hunger.

The house built by Hattie's grandfather stood on a brick foundation. The siding was longleaf pine, peeling now but painted regularly when Ladson was alive, as a sign of the owner's respectability. The two- story dwelling had piazzas on the east and west, and large windows open to sea breezes but covered when necessary by shutters that kept out hurricane winds and other intruders. Two large rooms opened off the downstairs hall. Two spacious bedrooms flanked the stairs on the second floor. It was to this house that Hattie and Legrand made their way with Amelia trailing.

Grandfather Lester, as was the custom, had built a covered walk from the residence to a small cookhouse, the cookhouse set apart as a precaution in case of fire. The pigpen was a short distance from the cookhouse, built against the wall of the big rice barn. Down the dirt track leading to the city road, six abandoned slave cabins were falling into ruin among some water oaks.

Hattie and Legrand cajoled Amelia into her pen. Hattie shut and latched the gate. "Come in and say hello to Mama." She led the way to the cookhouse. They found Sara at the old iron stove, her cheeks shiny from the heat. After a sojourn in the nippy air, Hattie was soothed by the warmth of the kitchen, although, as usual, the place was in terrible disorder.

Sara poked a long spoon into the pot of boiled crabs. "Hello, Legrand. Will you join us for dinner?" Sara had a sweet, round face, straw-colored hair she had passed along to her daughter, and a wan complexion compounded of too little nourishment and too much worry. Once, Hattie's mother had been a willowy beauty; lately she was rushing toward haggard middle age. It made Hattie sad.

Legrand said politely, "Can't, Mrs. Lester, but I appreciate the invite. Pa trapped a possum for us."

"A possum. How delicious." Hattie knew her mother loathed the smelly long-nosed creatures, whose meat was favored by the vanished slaves. But Sara was Sara; she would never embarrass a guest. Her late father, a Congregational parson, had taught her that, among many virtues.

"Any news from the front?" Sara asked as clouds of steam arose from the pot.

"Last we heard, the Yankees were aiming for Milledgeville."

"Oh, horrors." Sara pressed a hand to her well-shaped front. The capital was the symbol of Georgia's sovereignty, the home of important state offices and institutions.

"There's big news right here, though," Hattie said. Despite Legrand's visible embarrassment, she described his decision to serve on the defense lines when called.

"You're indeed a brave young man," Sara said. "We'll pray for your safety."

Legrand thanked her, wished them a happy day, and set off down the dirt track to the main road. Sara hugged her daughter. "Let the water cool awhile. Then you can pick the crabs."

"Are they cooked?"

"Thoroughly."

"Good." Hattie couldn't stand it when blue crabs were dropped in a pot of scalding water; they made a plaintive noise as they were boiled alive.

She left for a short visit to the outdoor necessary. She might have liked to change her sweaty frock, but she didn't have a better dress in her wardrobe; Sara's spinning wheel was broken. She'd sewn Hattie's dress out of multicolored scraps from her ragbag.

A sudden hail from the cookhouse brought Hattie rushing outside again. On the dirt track, a dust cloud rose in the fading daylight. A carriage. Sara stood on the cookhouse porch with a hand shielding her eyes. Hattie ran to her.

"Who is it, Mama?"

"I can't tell. I surely hope it isn't our nasty relative come to torment us again. He doesn't seem to understand the meaning of no."

Hattie put her arms around Sara's waist and watched the dust cloud billow.

Silverglass Plantation,

continued

A cold gust from the river parted the dust cloud and revealed their unexpected guest. It wasn't the nemesis Sara feared, her uncle by marriage, but Miss Vastly Rohrschamp of East York Street, the city. Miss Vee was Sara's best friend, a classmate from their boarding days at Pouncefort's Genteel Young Ladies' Academy down in Sunbury.

The visitor's first name suited her; despite wartime shortages, she weighed, by Hattie's best guess, at least 270 pounds. Her brown eyes resembled raisins stuck in a plate of dough, but she was uncommonly pretty even so. Miss Vee was patriotic: She refused to pay four hundred or five hundred dollars Confederate to some gouging milliner who offered bonnets imported illegally from shops in Bermuda or the Bahamas. Miss Vee had made her own hat, wheat straw bleached to remove its yellow cast and decorated with chicken feathers that whipped in the wind of her furious driving. She called a stentorian whoa to the lathered beast drawing her carriage and waved.

"Hello, hello --- there's the most awful news. I rushed out to tell you."

Sara ran to the carriage to help her friend alight. The carriage was an old Stanhope gig, its dark green paint faded, the pearl striping too. Miss Vee's late father was a gentleman physician, and the gig was a gentleman's conveyance. It was less suitable for a woman as seriously large as Miss Vee. The nag in the traces looked exhausted from hauling her bulk.

"Awful?" Sara repeated as she danced this way and that, ready to assist yet wary of being crushed if Miss Vee fell on her. "Tell us, for heaven's sake."

"As soon as I catch my breath."

Miss Vee came out of the gig backwards. Sara braced herself; Hattie kept her distance. Miss Vee landed successfully, without assistance, and drew a huge handkerchief from her sleeve. She fanned herself as though suffering a heat spell. Hattie couldn't understand the affection her mother felt for the scatterbrained woman, but the bond was certainly strong. Miss Vee survived in town by giving piano lessons in the house Dr. Rohrschamp had left her.

Sara repeated the invitation extended to Legrand. Miss Vee declined; she was dining later with parents of a pupil. "Then at least come into the parlor," Sara said. "Hattie will entertain you while I brew some tea."

"Heavens, you have real tea?"

"Ersatz," Sara said with a rueful smile. "It's a wonderful recipe, though --- holly leaves and twigs sweetened with a dot of molasses."

She dashed off to the cookhouse. Miss Vee took Hattie's hand, her multiple petticoats rustling. Miss Vee's dress, of sufficient size to cover a baby elephant, was made of good domestic homespun; not for her any dry goods smuggled through the blockade. The dress was prettily striped in a vertical pattern of blue on white, the direction of the stripes doing little to minimize the visitor's size.

As they stepped inside, Miss Vee said, "So many books. I am always astounded by the number of books your dear mother collects." From the hall onward, the dim interior of Silverglass was crowded with hundreds of volumes in all shapes and conditions, piled everywhere. Hattie didn't feel it necessary to say that most of the books were acquired before the war brought hard times and penury. Hattie moved Victor Hugo and William Gilmore Simms off the parlor sofa and invited the guest to sit.

"Oh, gladly. It's a long way out here." Two sofa legs creaked ominously under her weight. She took off her straw hat and laid it beside her. For herself, Hattie cleared a rocking chair of privately printed copies of the sermons of her maternal grandfather, Reverend Chider.

The state of the household frequently put Hattie in a funk. Like her father, she was an orderly person. Sara had many admirable qualities, including a kind heart, but she also had a disregard for housekeeping. The room felt less like a parlor than like a used-book store. Upstairs, under Sara's bed, more books were concealed: McGuffey primers and hornbooks Sara had used to teach Silverglass slaves to read and cipher. These were never mentioned to outsiders, not even to Miss Vee.

Of course, teaching slaves broke a long-standing state law, but Sara wasn't easily deterred. She insisted that regardless of when the Confederacy gave up, the unlettered black souls Lincoln had freed with his proclamation would need basic skills to survive. Ladson Lester had nervously given his wife permission to conduct her lessons in the slave cabins. There, by lamplight, Sara had taught the vanished men, women, and children --- including obnoxious Braxton, who'd stuck out his tongue at Hattie.

Miss Vee cast a wistful eye at the mantel of the brick fireplace; it was the one spot free of books. "I do so admire that photograph of your papa," she said. Next to a daguerreotype of Sara's parents, Reverend and Mrs. Chider, a similar photograph presented Ladson Lester as he was in 1860, a year before his inglorious death: a solemn oval face, a head already bald, a mustache full and down-sweeping, as though much of his hair had migrated south from his pate.

Hattie nodded in agreement; she loved the picture, though it hardly reflected the father she remembered --- the man whose blue eyes sparkled, who sang cheerfully as he worked, who hugged his wife and daughter with jolly abandon. Miss Vee responded to the picture for a different reason. Back in school, Sara confided, Miss Vee had been "disappointed in love," her heart permanently broken. She envied women more fortunate than herself.

Soon Sara arrived with a tray, an assortment of cups, and a blue pot from the kiln of a local potter. She poured three cups and passed them around. "Now, what is this awful news?"

"Milledgeville," the guest announced, as though someone had died. "Milledgeville has fallen."

"Oh, no."

"Oh, yes. Two days ago, Sherman's left wing took the town. The lad who rode to Savannah with the news said the barbarians had already moved out again, across the Oconee River bridge, coming this way, surely."

Hattie spoke up. "Our neighbor Legrand Parmenter was here a while ago. He said Milledgeville was in danger, but we didn't know it had been captured."

"Captured and vandalized. Atrocity after atrocity. The weather was frosty, like today. The Yankees chopped up church pews for firewood."

Sara shuddered. "Dreadful."

"There's more." Miss Vee leaned forward; again the creaks, and Hattie thought one end of the sofa sagged. "They looted the treasury of stacks of unsigned Confederate notes and lit their cigars with them. They carried fine books from the state library and threw them in the mud. They held a mock session of the legislature that lasted all night. That debauched devil Kilpatrick" --- Hattie recognized the name of the infamous general of Union cavalry --- "drunkenly orated on the merits of various whiskies."

"Where was Governor Brown while this was going on?"

"Fled, who knows where? The cowardly legislators too. That isn't the worst." Miss Vee's tone inspired a thrill of fear in Hattie. The day had become dusk; they needed to light the fatwood in the hearth to drive out the shadows and the chill.

"The vandals burned the state prison. The governor had already offered the inmates amnesty if they would enlist to fight. Some did; many did not. The Yankees set fire to the place, and the remaining inmates were released to run amok. There are" --- she lowered her voice --- "Sara, should your daughter listen to this?"

"This is wartime, Vee. Hattie is quite grown up. Please proceed."

"Well, all right. Between the escaped criminals and Sherman's plundering horde, I am reliably informed that no decent woman in Milledgeville was safe, not even in her own home. Women of all ages were --- outraged. Do you know what that means?"

"I have heard the expression." Sara's reply was sober, unemotional. Hattie had a vague idea of what Miss Vee was trying to say. She didn't quite understand the mechanics of men and women together, but she'd been around livestock most of her life and could fill in the gaps with imagination.

Sara asked, "Did the person who reported this actually witness any such outrages?"

"I don't believe so, but --- "

"Then let us hope these particular rumors are nothing more than that. I've never visited the North, although my father did, several times. I don't believe the Yankees are saints, but neither do I believe they're monsters."

"They are men, Sara. Lustful men. For months, perhaps years, they have been denied the wholesome calming influence of mothers, sisters, and sweethearts. Sherman allows them to have their way," she concluded with a finality that brooked no disagreement.

Sara sipped tea. Hattie balanced her cracked cup on her knee, unwilling to drink the dismal stuff; she'd spied a piece of bark floating.

"I appreciate your informing us, Vee. We'll pray that General Sherman can control his soldiers."

"What about the jailbirds running hither and yon? He has no control over them. Certainly some may come this way. Which brings me to the second reason for my visit. I want to offer you the sanctuary of my house. You and Hattie will be much safer in Savannah."

"There's Amelia," Hattie began.

"She is welcome too. Close up this place. Pack a valise, and come stay with me."

Hattie responded with a vigorous nod. The plantation had become fearfully isolated. Sara, however, had a contrary response: "Abandon Silverglass? I don't think I can, not yet."

"Don't wait too long," Miss Vee warned as she finished her tea and prepared to leave.

Sara and her friend exchanged sisterly hugs and kisses. Outside, the carriage horse seemed to cast a despairing eye at the fleshy passenger rolling toward him. Sara assisted her friend into the gig, and Miss Vee drove away, chicken feathers waving.

"She's a dear person," Sara said as they went inside again. "I don't doubt the Yankees have done some terrible things, but I refuse to believe all this talk of outrages. Not until there's evidence." She pondered a moment. "In regard to such threats to herself, perhaps Vee is --- um --- slightly too hopeful. Do you take my meaning, Hattie?"

"Yes, ma'am, I think so. It was generous of her to to offer us a safe place, though."

"Very generous," Sara agreed.

"Can't we go?"

"Only if it becomes necessary. I'll decide."

Which was the answer Hattie expected, and profoundly unsettling. Off in the November night, the Yankees were coming, possibly the convicts too.

Sara saw her daughter's anxious look, patted her gently.

"Help me find a lamp. If we don't pick those crabs, we'll never eat dinner."

November 27, 1864

Near Sandersville, Washington County

Wagons, he wrote, hundreds of wagons, inundating the land like Noah's flood or Pharaoh's plagues ---

No. Plumb, his irascible editor at the New York Eye, would slash that out, assuming he read it, which assumed eventual reestablishment of telegraph connections to the North. Plumb wanted war dispatches written in short, bleak sentences. Stephen tore the sheet from his pad and tossed it in the ditch behind him. He hailed from the city, where you disposed of trash that way. He licked the tip of his pencil and contemplated a new beginning.

Ah, but bleakness was hard; the passage of this army hour after hour invited fanciful allusions. The left wing was a chaotic, ever-changing spectacle: infantry columns slogging by --- the tall, tough, sunburnt "Westerners" from Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, feared in the South far more than Grant's immigrants and shopkeepers; then a dozen sutler's wagons; drovers herding cattle; a band of ragged Negroes, some with babes in arms. They followed the army without purpose or permission; Uncle Billy resented it.

Stephen observed the Sabbath spectacle from a shoulder of the sandy road leading to the county seat. Marauders had carried off most of a hand-hewn fence behind the ditch. The adjoining field ran to a forest of sixty-foot pines; the field had been trampled and rutted by horses and wagons of the army foragers --- "bummers," most people called them. The creak of iron wagon tires, the lowing of cattle, the cursing of teamsters, the singing of the black folks, the occasional distant pop of a weapon blended into a weird music. Not, however, the kind of music Stephen appreciated most.

Stephen was a slender, dark-haired chap of thirty-two. Large dark eyes and pleasing swarthy features spoke of his heritage: black Irish Presbyterian father, mother from the Italian community in Rochester. In 1852, their only son had decamped for the wicked metropolis to start his career by sweeping floors at the Eye on Park Row.

A dawn fog had lifted, but the sky remained cloudy. Elements of the XIV Corps commanded by Gen. Jefferson C. Davis continued to pass. Stephen had it on his mental task list to interview the unpopular and unfortunately named Jef Davis, but he didn't look forward to it.

From the direction of Sandersville he heard a regimental band triumphantly playing "Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!" --- quite a contrast with yesterday, when skirmishers from Joe Wheeler's cavalry, perhaps reinforced by home-grown partisans, had fought for thirty minutes in the streets of Sandersville before being routed. Uncle Billy was in a fury over that, as well as over the earlier delay at Buffalo Creek, where rebs had destroyed a series of small bridges, forcing Captain Poe and his engineers to repair or rebuild them before the army could progress.

Stephen stuffed his pad into the pocket of his travel-worn uniform blouse, jumped the ditch, and untied his mule. After a week on an Atlanta-bought horse that bucked or bolted at every round of rifle or artillery fire, Stephen heeded the advice of a teamster who handled a six-mule hitch; he traded the horse for the less skittish mule the seller had named Ambrose, to mock the hapless Union general, Ambrose Burnside, who had admitted to blundering at Fredericksburg. "Half an ass if not more," the seller said, but Stephen kept the name, quickly concluding that Ambrose the mule soldiered more effectively than his two-legged counterpart.

As he mounted, three officers on horseback appeared. Stephen recognized the major, three years older than himself, who was his favorite on Sherman's staff. He saluted. "Major Hitchcock."

"Captain Hopewell."

Stephen exchanged salutes with two lieutenants accompanying the sturdy, blunt-spoken lawyer who'd been assigned to Sherman in Atlanta, chiefly to handle his voluminous correspondence. Although Hitchcock was born in Alabama, his family came from New England; he'd studied at Yale and practiced in St. Louis. He said, "Are you riding to town?"

"Yes, sir. Did the rebs destroy it yesterday?"

"No, but the general's threatening to apply the torch. He's in one of his tempers. This doesn't help." Hitchcock produced a page of newsprint. "The Augusta Constitutionalist urges loyal Georgians to round up Union stragglers and, if surrender is refused, to --- I quote --- 'beautifully bushwhack them.' Care to read it?"

"I take your word, sir. Do you think the general will carry out his threat?"

"He'll burn the courthouse if nothing else. The rebs sniped at us from the second floor yesterday." Hitchcock observed Stephen's expression. "You don't wholeheartedly believe in this campaign, do you, Captain?"

Stephen answered candidly. "I saw no need for setting fire to Atlanta. Also, everyone says the foragers are badly disciplined."

"I'd argue the first point but grant you the second. The general set out to 'make Georgia howl,' as he phrases it. He wants to be the man to end the war."

"By punishing civilians."

"I would keep that opinion to yourself. You know what the general thinks of ink slingers."

Stephen quoted an overheard remark of Sherman's: "'It is impossible to carry on a war with a free press.'"

"Nevertheless," Hitchcock said, "the general does not make war on women and children."

Only on their homes, livestock, crops, and provender, Stephen thought. But he refrained from saying it. He held his rank by sufferance of the War Department. Uncle Billy detested journalists because certain of them had criticized him for erratic behavior in Kentucky in '62. The Cincinnati Commercial had actually called him insane --- "stark mad." He fought to ban all newsmen from his army. He lost the battle, and barely tolerated the clutch of reporters who, like Stephen, tagged along with the troops.

A dispatch rider appeared from the direction of Sandersville, bringing a message for the major. Hitchcock perused it quickly. "The general requires my presence immediately. Good morning, Captain." Off he galloped with his lieutenants following.

Ambrose proceeded at a walk while Stephen scribbled phrases on his pad. Suddenly, up ahead, he heard a woman wailing. Not suffering, exactly --- protesting. He dropped behind a four-wheeled ambulance, maneuvered through half a dozen plodding steers, and rode up to have a look.

The sight he came upon appalled him. A band of army foragers had picketed their horses in the dooryard of a large cabin set well back from the road, where the pine forest began. The bummers were a mixed lot: three callow privates, not long off the farm; a homely stoop-shouldered corporal with moles on his cheeks; a giant brown-skinned soldier Stephen took to be one of the Winnebago Indians marching with the army --- how had he gotten separated from his Wisconsin regiment? --- and finally, a sergeant. The sergeant was arguing with a stout lady at the cabin door.

"I never wanted this war," she cried. "You got no right to punish helpless women who never did nothing to harm you."

"Oh, yes?" said the noncom, his chin aggressively thrust forward. "Let me ask you --- where's your husband?"

"Off in the army, but --- "

"Did you use your influence keep him home?"

"No, but --- "

"Then you did all you could to help the war, and nothing to prevent it. Boys, this is a rebel house. Take whatever we can use."

The bummers stampeded inside while Stephen dismounted and approached the peculiar-looking sergeant. The fellow was tall, well muscled, sunburnt. Over his blue tunic he wore a cape improvised from an Oriental carpet. Huge silver spurs, not army issue, clinked and gleamed. He saluted lackadaisically and grinned, as though friendliness would protect him. Stephen snapped a salute in return. "Take off that ridiculous hat."

"Yessir." The young man doffed a black top hat decorated with artificial flowers; his blond hair hadn't been cut in a while.

"Whose horse is that?" Stephen indicated the animal whose open saddlebags bulged with ears of corn, yams, books, a silver candelabra, and a dead rooster. The sergeant allowed as how the animal was his. "Your name?"

"Alpheus Winks. Eighty-first Indiana."

"Where's the officer in charge?"

"Posted to the invalid corps, sir."

"Pretty far from your unit, aren't you?"

"Foragers are allowed to roam at will, sir."

"And plunder at will. Where did you steal those goods?"

"From reb houses already condemned to be burnt. Sir." The pause before the final word was pointed.

"Well, I don't approve."

Two of the farm boys dragged an old rug from the cabin. The stout lady watched, disbelieving, as they spread the rug in the weedy yard. The Indian ran out with a jug containing some kind of syrup, which he proceeded to pour all over the rug. The stout lady reeled back, gasping.

"That's criminal," Stephen barked. "Mount up and leave this property."

"Sir, we're only carrying out Uncle Billy's --- "

"General Sherman to you."

"General Sherman's Special Order Number One Hundred and Twenty. 'Forage liberally,' it says. That's what we're doing."

"Yes indeedy," said the corporal, standing in the cabin door with a pair of lapis lazuli ear pendants held up to his ears.

Winks looked uncomfortable. "Put those back, Professor. We don't make war on ladies."

"What do you call stealing their possessions?" Stephen exclaimed.

The corporal smirked. "I call it 'a place for everything, and everything in its place.' Mr. Emerson said that. I say the place for reb baubles is right here in my pocket. Just so's you know I'm not a lowlife, I taught the classics at Indiana Asbury College in Greencastle," he advised Stephen.

"Corporal Marcus, don't try to hornswoggle this here officer," Winks said. "You taught in a four-bit, run-down, one-room schoolhouse in Cloverdale. Now put those things back." The stout lady leaned against the cabin wall in a state of goggle-eyed suspense.

Yet the professor hesitated. "She's got a pump organ, Alph. Ought to be worth a few shekels." Stephen quivered with a guilty interest.

Winks shook his head. "We ain't in the business of mov- ing pump organs." He drew his sidearm --- an English-made five-shot .44, from the look of it. "Will you git, or do you need encouragement?"

The corporal vanished. Stephen said, "Marcus. I'll remember that name."

"Marcus O. Marcus," Winks said. "Putnam County, Indiana. We're all from there. I have to sit on the professor --- he'll steal anything. Thinks he's smarter'n the rest of us too."

A wild bleating announced two of the farm boys waving sticks and chasing a trio of hapless sheep. The third farm boy followed with a burlap sack; judging from the internal noise and commotion, it contained one or more anxious hens. The farm boys hoisted the sheep and burlap sack into a wagon parked by the road. The Indian clambered in to guard their acquisitions. The professor shambled out of the cabin, looking disgruntled.

Winks mounted his booty-laden horse and tipped his flowered top hat. "Pleasure meeting you, sir," he said to Stephen, meaning directly the opposite. They all rode away in the direction of Sandersville, quickly lost in the continual grinding confusion of the advance.

Stephen's face was a curious contrast of a beard already showing black since his early-morning shave and, above it, the scarlet of sunburn and frustration. Winks had a certain countrified charm, but he and his men were thieves. When the North won, as it surely would, the state of Georgia might harbor resentment forever, and not without reason.

The stout lady glared at Stephen and disappeared in her cabin after a last woeful look at her ruined carpet. Stephen wanted to see her pump organ but figured that even asking permission would tar him with the same brush used on the bummers.

December 1, 1864

Silverglass Plantation

A week after Miss Vee's visit, other unexpected guests came rolling up the road, not so welcome this time. "It's the judge and his whole clan," Sara informed Hattie. "Trailing clouds of spurious respectability." Sara loved Wordsworth, had in fact memorized many of his poems, including his "Ode on the Intimations of Immortality," which she readily paraphrased.

Hattie might have behaved during the visit but for an in- cident an hour before. Outdoors, among the magnolias, a brown canebrake rattler slithered from the spartina grass in hot pursuit of a dune rat. The rat escaped when Hattie inadvertently tripped over the snake.

Excerpted from Savannah © Copyright 2012 by John Jakes. Reprinted with permission by Signet. All rights reserved.

Savannah: Or a Gift for Mr. Lincoln

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- Mass Market Paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Signet

- ISBN-10: 0451215702

- ISBN-13: 9780451215703