Excerpt

Excerpt

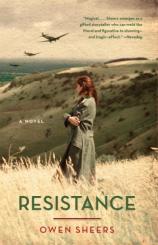

Resistance

SEPTEMBER --- NOVEMBER 1944

Everything

Would have been different. For it would have been

Another world.

Edward Thomas, “As the Team’s Head-Brass”

In the months afterwards all of the women, at some point, said they’d known the men were leaving the valley. Just as William Jones used to forecast the weather by studying the sky or the formations of migrating birds, so the women said they’d been able to forecast the men’s sudden departure. After all, they were their men, their husbands. No one could read them like they could. So no surprise if they should see what was coming. That’s what the women said in the long silence afterwards.

But in truth none of them saw any change in the men’s behaviour. None of them knew the men were leaving and in many ways this was the hardest part of what happened. Their husbands left in the night. Just days after news of the invasion came crackling through on Maggie’s wireless, propped on a Bible on her kitchen table, the men, lit by a hunter’s moon, met at William’s milking shed and slipped out of the valley. Moving in single file they walked through the higher fields and up over the Hatterall ridge; an ellipsis of seven dark shapes decreasing over the hill's shoulder, shortening to a last full stop and then nothing, just the blank page of the empty slope. The women, meanwhile, slept soundly in their beds. It was only in the morning when a weak September sun shone into the valley that they realised what had happened.

***

For Sarah Lewis it began in her sleep. The drag, rattle, and bark of the dogs straining on their chains was so persistent it entered her dreams. A ship in storm, the sailors shouting for help from the deck, their pink faces and open mouths obscured by the spray blown up the sides of the hull. Then the noise became Marley’s ghost, dragging his shackles over a flagstone floor. Clink,slump, clink, slump. Eventually, as the light brightened about the edges of the blackout curtain and Sarah surfaced through the layers of her sleep, the sound became what it was. Two dogs, urgent and distressed, pulling again and again on their rusty chains and barking, short and sharp through the constraint of their collars.

Without opening her eyes Sarah slid her hand across the sheet behind her, feeling for the warm impression of her husband’s body. The old horsehair mattress they slept on could hold the shape of a man all day and although Tom was usually up before her, she found comfort in touching the warm indentation of where he’d lain beside her. She stroked her palm over the thin cotton sheet. A few hairs poking through the mattress caught against her skin, hard and stubborn as the bristles on a sow’s back.

And there he was. A long valley where his weight had pressed the ball of his shoulder and his upper arm into the bed; a rise where his neck had lain beneath the pillow. She explored further down. A deeper bowl again, sunk by a protruding hip and then the shallower depression of his legs tapering towards the foot of the bed. As usual, Tom’s shape, the landscape of him, was there. But it was cold. Normally Sarah could still feel the last traces of his body’s heat, held in the fabric of the sheet just as the mattress held his form. But this morning that residue was missing.

With fragments of her dreams still fading under her lids, she slid her hand around the curves and indentations again, and then beyond them, outside the borders of his body. But the sheet was cold there too. The dogs below her window barked and barked, their sound making pictures in her mind’s eye: their sharp noses tugging up with each short yap, exposing the white triangles of their necks, flashing on and off like a warning. She lay there listening to them, their chains rising and falling on the cobblestones of the yard.

Tom must have been up early. Very early. Not in the morning at all but in the night. She turned on her side and shifted herself across the bed. The blankets blinked with her movement and she felt a stab of cold air at her shoulder. Pulling them tight about her neck, she lay there within the impression of her husband, trying not to disturb the contours of his map. Everything about her felt heavy, as if her veins were laced with lead. She was trying to think where Tom could be but the barks of the dogs were distracting her. Her mind was blurred, as buckled as a summer’s view through a heat haze. Why hadn’t he taken the dogs? He always took the dogs. Did he say something last night? She couldn’t remember. She couldn’t remember anything past their dinner. She opened her eyes.

In front of her the bedroom window was bright about the ill–fitting blackout cloth, a thin square outline of light burning into the darkened room. She blinked at it, confused. The window looked into the western flank of the valley, and yet there was light. Too much light. The sun must already be over the Black Hill on the other side of the house. She must have slept late. She never slept this late.

She rose quickly, hoping movement would dispel her mild unease. Tugging roughly on the heavy blankets, she made the bed, tucking their edges under the mattress. Then she plumped the pillows, shaking them as if to wake them. Brushing a few of Tom’s hairs from the one beside hers she paused for a second and stilled herself, as if the hairs might summon Tom himself. She listened, one hand still resting on the pillow. But there was nothing. Just the usual ticks and groans of the old building waking and warming, and outside, the dogs, barking and barking.

She pulled back the blackout cloth and opened the thin curtains behind it with both hands, unveiling the room to light. It was a bright, clear day. She closed her eyes against the glare. When she opened them again white spots shimmered over her vision. Drawing the sleeve of her nightdress over her wrist she wiped away the veneer of condensation from one of the small panes and looked down into the yard below. The dogs, both border collies, both bitches, sensed the movement above them and barked and strained harder in response, pulling their chains taut behind them. Sarah looked above the outhouse where they were tied. Over the top of its jigsaw slate roof she could see the lower paddock rising up to meet the sweep and close of the valley’s end wall. Except for a few grazing sheep it was empty, and so were the steep–sided hills on either side, their edges bald against the blue sky.

Turning away from the window, she pulled her nightdress over her head. Again she felt the cold air on her skin. The dress's neckline held her hair for a moment, then let it go all at once so it fell heavily about her shoulders. She sat on the edge of the bed, put on her knickers, a vest, and began balling a pair of woollen stockings over her hand, her forehead puckered in a frown. Catching herself in the dressing–table mirror she paused and ran a finger up the bridge of her nose between her eyebrows. A slight crease was forming there. She’d only noticed it recently; a short line that remained even when her brow was relaxed. Still sitting on the edge of the bed she gathered up her hair and, turning her profile to the mirror, held it behind her head with one hand, exposing her neck. That crease was the only mark on her face. Other than that her skin was still smooth. She turned the other way with both hands behind her head now. She should like a wedding to go to. Or a dance, a proper dance where she could wear a dress and her hair up like this. That dress Tom bought for her on their first anniversary. She couldn’t have worn it more than twice since. Tom. Where was he? She dropped her hair and pulled on her stockings. Reaching into the dressing–table drawer, she put on a blouse and began doing up the buttons, the crease on her forehead deepening again.

Bad news had been filtering into the valley every day for the last few weeks. First the failed landings in Normandy. Then the German counterattack. The pages of the newspapers were dark with the print of the casualty lists. London was swollen with people fleeing north from the coast. They had no phone lines this far up, and apart from Maggie’s farm, which sat higher in the valley, the whole area was dead for radio reception. But news of the war still found its way to them. The papers, often a couple of days old, the farrier when he came, Reverend Davies on his fortnightly visits to The Court, all of them brought a trickle of stories from the changing world beyond the valley. Everyone was unnerved but Sarah knew these stories had unsettled Tom more than most. He rarely spoke of it, but for him they threw a shadow in the shape of his brother, David. David was three years younger than Tom. He’d had no farm of his own so he’d been conscripted to fight. Two months ago he was declared missing in action and, while Tom maintained an iron resolve that his brother would appear again, the sudden shift in events had shaken his optimism.

For Sarah news of the war still seemed to have an unreal quality, even when a few days ago the names of the battlegrounds changed from French villages to English ones. There were marks of the conflict all about her: the patchwork of ploughed fields down by the river once kept for grazing; the boys from her schooldays, and the farmhands, many of them gone for years now. But unlike Tom she didn’t have a relative in the fighting. Her own older brothers had been absent from her life ever since they’d argued with her father and broken from the family home when she was still a girl. They’d bought a farm together outside Brecon, large enough to have saved them both from the army. So Sarah didn’t possess that vital thread connecting her to the war that brought the news stories so vividly to life for so many others. There were women here, in the valley, who had lost sons, and in the early years she’d seen other mourning mothers and wives in Longtown and Llanvoy. But even these women, with their swollen eyes and dark dresses, seemed to have passed into a different place, a parallel world of grief. The sight of them evoked sympathy in Sarah, sometimes a flush of silent gratitude that Tom was in a reserved occupation, but never empathy.

Only once in the last five years had the war really impacted upon her. When the bomber crashed up on the bluff. Then, suddenly, it had become physical. She’d been woken by the whine of its dive followed by the terrible land-locked thunder of its explosion. Tom held her afterwards, speaking softly into her hair, “Shh, bach, shh now.” In the morning they’d all gone up to look. Tom and she took the ponies. When they got there the Home Guard and the police from Hereford had already put a cordon around the wreckage so they just stood at a distance and watched, the thin rope singing and whipping in the hilltop wind. Beyond the crashed plane she'd glimpsed a tarpaulin laid over a shallow hump. “One of the crew,” Tom had said with a jerk of his chin. She’d agreed with him. “Yes, must be,” although she’d thought the hump looked too small, too short, to be the body of a man. The ponies shifted uneasily under them, pawing the ground, tossing their heads. They were disturbed by this sculpture of twisted metal that had appeared on their hill, by this charred and complicated limb half embedded in the soil as if it had erupted from the earth, not fallen from the sky. And so was Sarah. She’d heard about the Blitz, and about Liverpool and Coventry, its cathedral burning through the night. She’d even seen their own bombers out on training runs. But she’d never seen an enemy plane before. Usually they were just a distant drone to her, a long revolving hum above the clouds as they returned from a raid on Swansea or banked for home after emptying their payloads over Birmingham. But now, here was one of them, on the hill above her farm. Massive and perfunctory. So ordinary in its blunt engineering. And under that tarpaulin was a real German. A man from over there who had flown over here to kill them.

She dressed quickly in a long skirt and cardigan and went downstairs to pull on her boots in the porch by the kitchen door. As she bent to lace them, she noticed Tom’s weren’t there. Not just his work boots but his summer ones too; both pairs were missing. She stared for a moment at the space where they’d been, four vague outlines in a scattering of dust blown in under the door. Leaning forward on her knee, she touched one of these empty footprints as if it could tell her where he’d gone. But there was nothing, just the cold stone against her fingertips. She shook her head. What was she doing? She stood up, took her coat from the hook on the back of the door, pushed her arms through its sleeves, and drew its belt tight about her waist. Lifting the door’s latch she stepped out into the brightness of the cobbled yard where the day fell in on her with a cool wash of air. She breathed in deeply, feeling the first metallic tang of autumn at the back of her throat. Shards of sunlight reflected off the stones. The dogs barked faster and louder to greet her. She moved towards them and they settled back on their haunches, stepping the ground with their forepaws, quivering with anticipation as if a voltage ran under their skins.

***

The dogs, let loose of their chains, wove and slipped about her as she walked up the slope across the lower paddock and through the coppiced wood behind the farm. The extra hours of restraint had charged them with a frantic energy and they raced ahead of her, ears flat, before doubling back, their sorrowful eyes looking up at hers, their heads low and their coats slickly black in the dappled sunlight. Sarah, in contrast, felt her legs heavy and awkward beneath her. She took the slope with more pace, pressing the heels of her palms into her thighs with each step. Twice she found herself stopping to rest against the trunk of a tree. She was twenty–six years old, worked every day and was usually through this wood before she knew it, but this morning it was as if one of the dogs’ chains had snagged around her feet and was dragging her back down the hill with every step she took.

Excerpted from Resistance © Copyright 2012 by Owen Sheers. Reprinted with permission by Anchor. All rights reserved.

Resistance

- paperback: 306 pages

- Publisher: Anchor

- ISBN-10: 0307385833

- ISBN-13: 9780307385833