Excerpt

Excerpt

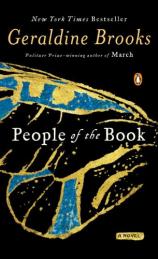

People of the Book

(Pages 257-258)

When the sun had set and darkness sheltered her from the eyes of the curious, Ruth Ben Shoushan walked into the sea, the nameless infant tight against her breast, until she stood waist deep. She unwrapped him, throwing the swaddling cloth over her head. His brown eyes blinked at her, and his small fists, free of constriction, punched at the air. “Sorry, my little one,” she said gently, and then thrust him under the dark surface.

The water closed around him, touching every inch of his flesh. She had a firm grip around his upper arm. She let go. The water had to take him.

She looked down at the small, struggling form, her face determined, even as she sobbed. The swell rose and slapped against her. The tug of the receding wave was about to pull the infant away. Ruti reached out and grasped him firmly in her two hands. As she lifted him from the sea, water sluiced off his bare, shining skin in a shower of brightness. She held him up to the stars. The roar in her head was louder now than the surf. She cried out, into the wind, speaking the words for the infant in her hands. “Shema Yisrael, Adonai eloheinu, Adonai echad.”

Then she drew the cloth from her head and wrapped the baby. All over Aragon that night, Jews were being forced to the baptismal font, driven to conversion by fear of exile. Ruti, exultant, defiant, had made a gentile into a Jew. Because his mother was not Jewish, a ritual immersion had been necessary. And now it was done. Even as the emotion of the moment brimmed within her, Ruti was counting up the days. She did not have very long. By the eighth day, she would need to find someone to perform his bris. If all went well, this would be in their new land. And on that day, she would give the child his name.

She turned back toward the beach, hugging the baby tightly to her breast. She remembered she had the book, wrapped in hide, slung in a shoulder sack. She pulled on the straps to raise it out of the reach of the waves. But a few drops of saltwater found their way inside her careful wrappings. When the water dried on the page, there would be a stain, and a residue of crystals, that would last five hundred years. In the morning, Ruti would begin to look for a ship. She would pay the passage for herself and the baby with the silver medallion that she had pried off the leather binding, and where they made landfall—if they made landfall—would rest in the hand of God.

But tonight she would go to her father’s grave. She would say the Kaddish and introduce him to his Jewish grandson, who would carry his name across the seas and into whatever future God saw fit to grant them.

(Pages 275-276)

We do not feel the sun here. Even after the passage of years, that is still the hardest thing for me. At home, I lived in brightness. Heat baked the yellow earth and dried the roof thatch until it crackled.

Here, the stone and tile are cool always, even at midday. Light steals in among us like an enemy, fingering its narrow way through the lattices or falling from the few high panes in dulled fragments of emerald and ruby.

It is hard to do my work in such light. I must be always moving the page to get a small square of adequate brightness, and this constant fidgeting breaks my concentration. I set down my brush and stretch my hands. The boy beside me rises unbidden and goes to fetch the sherbet girl. She is new here, in the house of Netanel ha- Levi, and I wonder how he came by her. Perhaps, like me, she was the gift of some grateful patient. If so, a generous one. She is a skilled servant, gliding across the tiles silent as silk. I nod, and she kneels, pouring a rust-colored liquid that I do not recognize. “It is pomegranate,” she says, in an unfamiliar tribal accent. She has green eyes, like agate stone, but her skin gleams with the tones of some southern land. As she bends over the goblet, the cloth at her throat falls away and I note that her neck is the golden brown of a bruised peach. I puzzle on what hues I would combine to render this. The sherbet is good; she has mixed it so that the tartness of the fruit still tells beneath the syrup.

‘‘God bless your hands,” I say as she rises.

“May the blessings be abundant as rain upon your own,’’ she murmurs. Then I see her eyes widen as they fall upon my work. As she turns, her lips begin to move, and though her accent makes it difficult to be sure, I think that the prayer she whispers is of a different import entirely. I look down at my tablet then and try to see my work as it must appear to her. The doctor gazes back at me, his head tilted and his hand raised, fingering the curl of his beard as he does when he considers some matter that interests him. I have him, there is no doubt of it. It is an excellent likeness. One might say he lives.

No wonder the girl looked startled. It puts me in mind of my own astonishment when Hooman first showed me the likenesses in the paintings that had enraged the iconoclasts. But it is Hooman who would be astonished if he could see me now: me, a Muslim, in the service of a Jew. He did not think he was training me for such a fate. For myself, I have grown accustomed to it. At first, when I came here, I felt ashamed to be enslaved to a Jew. But now my shame is only that I am a slave. And it is the Jew, himself, who has taught me to feel this.

People of the Book

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 372 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0143115006

- ISBN-13: 9780143115007