Excerpt

Excerpt

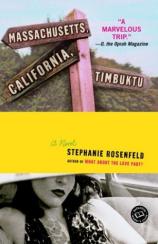

Massachusetts, California, Timbuktu

THE YEAR OF THE CAT

It wasn't really the year of the cat --- that was just a stupid song on All Oldies All the Time Mom liked to go around singing, even though she didn't know any of the words except for that one line.

"The year of the cat!" she'd blurt out in a half-talking, half-singing voice, and you'd wait for her to connect it to something --- a thought or a reason or another piece of the song --- but she'd just go back to what she was doing. She got Rona doing it, too, and sometimes the two of them would sing it to each other a hundred times a day, wiggling their eyebrows and hunching their shoulders, like two aliens telling each other a fascinating fact in the language of their planet.

Mom had gotten Rona a cat; that was why she'd originally started saying, "The year of the cat!" Every time the cat walked by, she'd bend down and look it in the eye and say it. Sometimes she'd make a claw in the air with her hand, and the cat would flinch and jump sideways. I felt sorry for the cat, because I could tell it was losing its mind, but Mom, of course, didn't seem to notice.

Mom's noticing was weird: Mom noticed everything, actually. She just noticed things in kind of an abnormal way.

"Did you see that woman's checkbook?" she might say in the grocery store. "It was made of very fine leather. She probably got it in Europe. She's probably from Europe --- her facial structure was very aristocratic."

"Did you notice Kristoffer Billings lit his cigarette with House of Tibet matches? I wonder if he's interested in Eastern culture and religion. His clothes smell like incense --- I'll bet he's a very spiritual person."

As far as noticing things about me, Mom was going through a phase I particularly didn't like. It reminded me of when your teacher comes around to admire your art project and she picks it up totally upside down and says, "How fascinating --- look, everybody!"

"Oh, look!" Mom said to me one day in the bathroom, right in front of Rona. I was trying to give myself a French braid after my shower. "A hair!" She tickled me in the armpit. "Congratulations, Justine!"

"Is something the matter, Justine?" she'd ask if I came home from school down in the dumps. "Did something happen?"

Sometimes I wanted to answer her, but then before I could think of what the real answer was, she'd say, "Is it a boy?" She had started to ask me that all the time; she'd study my face and give me a weird, slanty smile I hated, and I started to think I knew how that cat felt: I wished I could jump onto the mantel and arch my back and look down on her from far away, too.

The cat was supposed to be a present to butter us up about moving --- that was one of those things I figured out later, like a missing puzzle piece you find in a dusty corner behind the door a long time after you've given up without finishing and put the puzzle away.

"Don't you just love cats?" Mom asked one day, standing at the kitchen sink. She was doing dishes, looking out the window at the sky; I was reading a magazine, not about cats; and Rona was coloring, not a picture of cats. I looked all around the room, I checked the yard through the window, but I couldn't figure out where that thought had come from.

My new idea was that if I could figure out where an idea came from before it popped out of Mom's mouth like a magician's paper flower, I would be able to cut down on my stress. I personally didn't care about stress, but when Mom came home from parent-teacher conferences last time, she walked in the door and said, "Fifth-graders aren't supposed to have stress, Justine!" and burst into tears.

There's a long list of things that make Mom cry, and I try to keep them from happening. I actually used to have a page in my notebook for writing them down, but I quit making it when it started to get too weird to read: when besides the normal things like the toilet backed up again, or they called to say they were turning off the electricity, there were things like she lost the ticket stub from some hippie concert twenty years ago where she met the guy she should have married but never saw again, or the color of the dryer lint made her remember a sweater she once had when she was an exchange student in Belgium, back when she thought she would become an archaeologist when she grew up, but now she was only someone who worked in a deli and sometimes did catering and couldn't even say one sentence in Flemish anymore.

I didn't know what to do about stress, though. I stole a booklet from the health center when we went for Rona's skin corrosion, but the suggestions were idiotic: Sit down when you eat your meals; stop and smell the roses; enroll in a yoga class. The only thing I could think of was to try to smile more, which didn't work, because then Mom would say, "What are you smiling about?" and jiggle her eyebrows and look at me as if we were about to have a big, juicy mother-daughter moment.

"Don't you just love cats?" she said again. She'd finished the dishes, and she wasn't looking out the window anymore; she had turned around and was looking at me and Rona like someone was supposed to answer her. Then she said, "Do you remember Marie and Bill? Remember the pictures Marie sent, of their kids, and their farm in Massachusetts? Justine? Remember?"

I tried not to answer questions with the names of people or places in them, because they always led to other questions that I really didn't want to answer.

"Remember the time we visited Arizona?" she might say --- something that sounded like a perfectly normal question. "The sun, the mountains, wasn't it beautiful there, Justine? You liked Arizona, didn't you?"

Then if I said, "Yeah, I guess," she'd say, "So, would you like to move to Arizona?"

Or, "I met someone named Kristoffer with a K today. Isn't that an interesting way to spell it?" She'd just keep asking till I answered.

"Yeah, I guess."

"That's what I thought, too! Well, would you like to meet him?"

Rona didn't understand the trick yet, though.

"Oh!" she was saying. "I love cats!"

"If you had a cat," Mom asked her, "would you be a happy little girl?"

The cat came in a Ryder box. I should have figured it out right then, but I didn't.

Mom came home from work one afternoon, a few days after she'd brought up the cat question, carrying the cardboard box, and when I saw the look on her face, I knew what was in it.

"Ta-da!" she sang, and she handed the box to Rona.

"Oh!" breathed Rona. Rona gave me the box so she could reach inside and take out the cat.

"I don't want that," Mom said when I tried to hand her the box. "Take it outside."

"His name's going to be Blackie," Rona said when I came back in.

"You can't just name everything after the color it is," I told her. We had already had two fish named Greenie and Whitey and a snake named Tanny.

"Justine," Mom said to me, "is something the matter?"

"I don't want a cat," I told her.

"Can it be mine?" Rona asked Mom.

"Yes, it can, sweetheart," Mom answered, putting her hand on Rona's head and smiling down at her.

"Who's going to take care of it?" I wanted to know. I had had to take care of the fish and the snake all by myself, and they'd all died, one by one, even though I hadn't done anything wrong.

"I will!" said Rona.

"Well, what about when she doesn't?"

"Then I will," Mom said in a tone of voice like the answer was obvious, and like it wasn't very important anyway. Then she gave that cat a look as if it were lucky to have ended up in a life with us.

"Today is the first day of the rest of your life," she told it, which was a deep thought she liked to say sometimes. And which, I have to admit, I liked a lot until I realized it was only a deep thought if you didn't say it all the time.

Mom never actually said the words, "We're moving." One day I came home from school and there were all these Ryder boxes in the living room.

"What are these for?" I asked.

"Just to put a few things into," Mom said. When I asked why, she said, "Oh, just in case." When I asked, "Just in case of what?" she pretended to lose her train of thought.

One night about a week later, we were sitting in front of the TV watching women's gymnastics, which was a show I didn't like. It wasn't women, first of all, it was girls, and it bothered me that they kept calling them the wrong thing: "These women work so hard"; "You couldn't find a more dedicated group of women." If the camera went up close, though, you could see they were little freakazoids, with big heads and tiny bodies. They looked like seven-year-olds with little breasts and makeup, and they'd say things like how hard it was, but also kind of fun, to be living in their own apartment with a chaperone, in a different city from their parents, and about how they didn't have any friends or do any normal kid things because they worked fifteen hours a day on gymnastics.

"What incredible drive that would take," Mom said, then she said, "Speaking of drives," and she sat up and muted the sound on the TV. She put her arm around Rona and her other arm around me. "Remember when I was telling you about Massachusetts? About what a neat place it is? And how much you liked it there?" Rona was nodding her head; she was such a sucker.

"And Justine, do you remember Marie, my good friend who knew you when you were just a baby?" I was one year old and Rona wasn't born the time we visited.

"No," I answered.

"Oh, sure you do!" she said.

On TV, the girl I liked best was on the balance beam. The reason I liked her was that she was bigger than the others. And even though she was totally coordinated, there was something a little bit awkward about her, too, like maybe her hands and feet were slightly too big for the rest of her, so that it almost looked like a real person might be about to climb out of her strange girl-woman body, like a baby dinosaur out of an egg.

"Well," said Mom, "Marie invited us to Massachusetts. We're going to go stay with them for a while --- with Marie and Bill and their kids, who you're really going to like!"

"Goody!" piped Rona.

I wished they'd both be quiet. They were wrecking my concentration. The girl on the beam was getting ready to do something --- you could tell by the way her ribs were getting huge, she was breathing in so much air. She looked like she was waiting for something --- for the exact right moment, maybe, that she knew was about to fly by like a bird, and when it did, she was going to catch it.

Anyway, what did it mean, that Marie had invited us to Massachusetts?

On the television, the girl suddenly launched into a front flip, the kind with no hands --- the kind where, if you mess up, you come down right on the top of your head and either die or have to spend the rest of your life in a wheelchair --- and I was so mad at myself: I closed my eyes. I did it every time. When I'd open them a split second later, there she would be, standing with her arms outstretched, and once again I had missed the part I wanted to see.

"Remember Danny Martone?" Mom said. A commercial for Sara Lee coffee cake had come on. Maybe Mom and Danny Martone had once had coffee cake together. Rona had her thumb in her mouth, watching with fascination as the coffee cake got its creamy white glaze poured on.

"You met him at a Germs concert," Mom said to me. "When you were about three. He was in town with his band, and they came to our house to spend the night, remember? He lives in Connecticut now --- Hartford, I think. That's right next to Massachusetts."

When she said that, something weird happened. The split sec-ond before she said "Massachusetts," I knew what was going to happen: Two days after we got to Marie and Bill's, Mom would suddenly get a burst of energy; she'd start calling 411, writing down numbers, getting out maps. Then we'd go to the library; and the day after that we would go to Hartford, which would suddenly be, according to Mom, a very interesting, historical place we had always wanted to see.

Massachusetts, California, Timbuktu

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 416 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 034544826X

- ISBN-13: 9780345448262