Excerpt

Excerpt

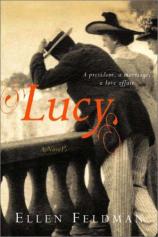

Lucy

The front door swung open, the floorboards sang under his shoes, and the house swelled with his presence. Bully, he liked to say, and dee-lightful, tickled pink, and Grand. Isn't it grand!

"Hello, Babs!" he called now, and his voice, big, resonant, caressing as the navy cape he'd later take to wearing, floated down the hall and encircled the two of us. We were working side-by-side in the comfortable, cluttered room overlooking a small garden with a rose arbor on the edge of bloom.

Two years had passed since I'd sat here drinking tea with Eleanor, whom I still called Mrs. Roosevelt. In Sarajevo, which many Americans could now locate on a map, a Slav nationalist had pulled the trigger. The archduke and his wife had died. Half a million young men were dying at Verdun. In a month and a half, twenty thousand British soldiers would die in the first day of fighting on the Somme, a hundred thousand before the battle was over. The numbers should have put matters in perspective. They only made the war more incomprehensible.

There were happier developments. Hobble skirts were out. Hemlines were up. Corsets were smaller. War has a way of shrinking clothing and unlacing restraints.

"Hello, Babs," he called again and was in the room with us before the words died. "And the lovely Miss Mercer," he said when he saw that I was there too.

The-lovely-Miss-Mercer, as if it were one word, was another of his expressions. I knew it was a joke, but I also knew that he wouldn't say it if he didn't think there was a kernel of truth in it. Women look at their less attractive sisters and compliment them on their luxuriant hair or fine complexions or sunny smiles. There is always one redeeming feature. But only a heartless man would tease a girl about being lovely if he did not think she were, at least a little.

There was a note of surprise in his voice when he pronounced my name. I was not supposed to be there at that hour when the last rays of afternoon light were slanting through the windows, glancing off the disarray of family photographs and nautical prints, rare books and stuffed birds, stamp catalogues and ship models, the whole motley clutter of possessions that Eleanor was always moving from house to house in New York and Albany and Washington. I was fond of that room, though I couldn't have said why. It was not aesthetically pleasing. The wallpaper was muddy, the walnut furniture gloomy, the carved mantelpiece heavy over worn tiles. It was what Mama, who had worked as an interior decorator during one interlude of reduced circumstances, would call haute respectable. I had worked with Mama briefly, and I loved beautiful things, but I also had a secret affection for haute respectable.

I didn't even mind the clutter. It gave the room character, his character, because the prints and books and stuffed birds and catalogues belonged to him. Franklin was a passionate collector. He was always joking about being in debt to dealers of one sort or another. I was surprised. It was bad enough to speak of money. I couldn't imagine joking about owing it. I still can't.

"Miss Mercer," he went on, "haven't you heard of the fifty-four-hour law for women and children? It was one of the first bills I put through when I went to Albany."

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Eleanor look up from the letter she was writing, frown, then go back to her task.

"But this is the District of Columbia, Mr. Roosevelt. Your New York State laws don't apply."

He laughed, and I preened, and across the room Eleanor's pen went on scratching.

Lucy

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393325105

- ISBN-13: 9780393325102