Excerpt

Excerpt

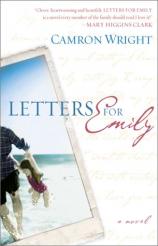

Letters for Emily

Chapter One

My bed is frigid and the room dark. I've placed many blankets on my bed, but they don't stop the cold Wasatch wind that penetrates to my bones. I stare through the window at my snow-covered plants and realize I will miss my garden. I will miss the way the carrots emerge from seeds not much bigger than dust. I will miss thinning beets in the late spring. I will miss digging for new potatoes in the fall. I will miss harvesting buckets of zucchini for unsuspecting neighbors who will then have no idea what to do with them; and I will even miss watching the plants turn brown and die each year as winter sets in.

My garden has taught me that every living thing must die. I have watched it happen now for scores of years -- I only wish I could have a few more summers in my garden with Emily.

I have other grandchildren, and I don't mean to play favorites, but the others live far away and seldom visit. Emily visits with her mother every Friday. Though our ages are more than seven decades apart, Emily and I are best friends.

My name is Harry, a laughable name for a man who's been completely bald most of his life. But, hairy or not, it's my name nonetheless. It was my father's name before me, and his father's before him. I wish I could say it was a name I passed on to my own son. I can't. When he was born and it came time to give him a name, we chose Bob instead. He rarely visits; he never writes. Now, on occasion, I wish I'd named him Harry as well.

Strangely, I'm not bitter about what is happening to me. Why should I be? I am no better than anyone else. I am no wiser, no stronger, and no smarter. (Okay, I am smarter than ol' man Ross who lives next door but that's beside the point.) So then, why not me?

I hope to go quickly so I'll be remembered as Grandpa Harry and not as the person I'm becoming. I fear I'll be remembered as a contemptible, cranky old man and that thought sickens me. The fact is, I'm losing my mind. I have Alzheimer's -- an insidious disease that causes the nerve cells in the brain to degenerate. As it works its havoc, the brain shrinks and wastes away -- dementia sets in, causing disorientation and confusion. There is no cure, no way to slow its determined progression.

This disease is a thief. It begins with short spells of forgetfulness, but before it's finished, it steals everything. It takes your favorite color, the smell of your favorite food, the night of your first kiss, your love of golf. Droplets of shimmering water cleansing the earth during an invigorating spring shower simply become rain. Mammoth snowflakes blanketing the ground in white at the onset of winter's first storm merely seem cold. Your heart beats, your lungs suck in air, your eyes see images, but inside you are dead. Inside your spirit is gone. I say it is an insidious disease because in the end, it steals your existence -- even your very soul. In the end I will forget Emily.

The disease is progressing, and even now people are beginning to laugh. I do not hate them for it; they laugh with good reason. I would laugh as well at the stupid things I do. Two days ago I peed in the driveway in my front yard. I had to go and at the time it seemed like a great spot. A week before, I woke up in the middle of the night, walked into the kitchen, and tried to gargle with the dishwashing liquid that is kept in the cupboard beneath the sink. I thought I was in the bathroom, and the green liquid was the same color as my mouthwash. I get nervous. I get scared, and I cry; I cry like a baby over the most ridiculous things. During my life, I've seldom cried.

There are times when I can still think clearly, but each day I feel my good time fading -- my existence getting shorter. During my good spells, now just an hour or two a day, I sit at my desk and I write. I crouch over the keyboard on my computer and I punch the keys wildly. It's an older computer, but it serves its purpose well. It's the best gift Bob has given me in years. It's an amazing machine and every time I use it, I marvel at how it captures my words. Younger people who have grown up with computers around them don't appreciate the truly miraculous machines they are. They create magic.

I'm not a good writer, but I've loved writing stories and poems all of my life. Writing always made me feel immortal -- as if I were creating an extension of my life that nothing could destroy. It was exhilarating.

I no longer write for excitement. There are times when my back aches and my eyes blur, and I can't get my fingers to hit the right keys, but I continue. I write now for Emily. She is just seven years old. I doubt she'll remember my face; I doubt she'll remember the crooked fingers on my wrinkled hands or the age spots on my skin or my shiny, bald head. But hopefully, by some miracle, she will read my stories and my poems and she'll remember my heart, and consider me as her friend. That is my deepest desire.

At times I feel bad that I'm not writing to my other grandchildren, but I hardly know them. While they visit every Christmas, they don't stay long. They are courteous, but they treat me like a stranger. It's not their fault. I'm not angry with them, and I hope they aren't angry with me.

My worst fear is that before I finish, I will slip completely into the grasp of the terrible monster, never to return. If this happens, my prayer would be that those around me might forget -- but they will not forget -- and then, worse than being forgotten, I will be remembered as a different person than I truly am. I will be despised.

I vow not to let this happen, so during my good times, I write -- I write for Emily.

Letters for Emily

- hardcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: Atria

- ISBN-10: 0743444469

- ISBN-13: 9780743444460