Excerpt

Excerpt

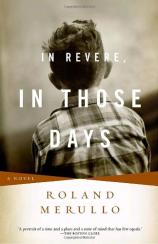

In Revere, In Those Days

The story does not take place here in Vermont, but in a small city called Revere, Massachusetts, which lies against the coastline just north of Boston. Three miles by two miles, with a salt marsh along its northern edge and low hills rising like welts in an irregular pattern across its middle, Revere must seem to the outside eye like an uninspiring place. The houses stand very close to each other and close to the street -- plain, wood-frame houses with chain-link fences or low brick walls surrounding front yards you can walk across in six steps. These days the city has a crowded, urban feeling to it: sirens in the air, lines of automobiles and trucks at the stoplights and intersections, thin streams of weeds in the tar gutters.

But forty years ago, Revere was a different place. There were amusements and food stands along its curve of sandy beach, making it a sort of slightly less famous Coney Island. And there were still some open lots pocking the narrow streets, blushes of wildness on the tame city skin. Not far from where I lived, a mile west of the beach, was a large tract of undeveloped land we called "the Farms," though nothing had been cultivated there since before the Korean War. For my friends and me, for city kids like us, the Farms was a landscape from a childhood fable: pastures, boulders, half-acre ponds, fallow fields where we turned over stones and planks and pieces of corrugated metal and reached down quick and sure as hunters to take hold of dozing snakes -- brown, green, black. The snakes would slither and writhe along our bare wrists, and snap their toothless gums against the sides of our fingers, and end up imprisoned in mayonnaise jars with holes banged into the metal tops. We carried them home like bounty from a war with the wilderness, and sold them to younger boys for ten or fifteen cents apiece.

The automobile had not yet quite been elevated to the position of worship it now holds. The streets were freer and quieter. Hidden behind the shingled, painted houses were backyards in the European style, with vegetable gardens given preference over lawns, with fruit trees and grape arbors, and ceramic saints standing watch over a few square feet of flower bed.

Revere is a thoroughly modern place now, a corner of blue-collar America with chain stores and strip malls and yellow buses lined up in front of flat-roofed schools. A hundred new homes have been squeezed onto the Farms, streets cut there, sewer and electric lines brought in. But in some way I have never really understood, the city had a mysterious quality to it in those days, as if it lay outside time, beyond the range of vision of the contemporary American eye. Provincial is a word you might have used to describe it. But provincial means that a community believes itself to be living at the center of the universe, that it refuses to make an idol of the metropolis. Revere was provincial then, in that way. And, I suppose, proud of it.

Even in the days when Jupiter Street was quiet enough for nine uninterrupted innings of a local game called blockball, even then there was an underside to the life we believed we were living. The collection of bad characters known as the underworld, or the mafia, or the mob, had a number of nests in Revere. These people, in my experience, in the experience of almost everyone in the city, had little in common with the fantasy underworld you see these days on movie and television screens. For most of us, the face of the mafia was found in nothing more terrifying than a coterie of local bookmakers' neighbors, family friends, the guy beside you in the pew at nine o'clock Mass -- men who made their living from the yearning of their neighbors toward some higher, softer life. In this way perhaps they were not so different from modern-day suburban portfolio managers.

The people in our neighborhood did not have executive jobs, did not commute into the city in suits and nice dresses, reading neatly folded copies of the Wall Street Journal, did not have parents and grandparents who had gone to college, and, with one or two exceptions, did not go to college themselves. They rode the subway into offices and warehouses in Boston, or drove their five-year-old Chevies to the factories in Lynn -- where my father worked, in fact -- and spent their lives in bland cubicles or hot, loud workrooms, performing the same few tasks again and again as their youth dribbled away. On Fridays they took a dollar from their pay envelope, walked down to the butcher shop on Park Avenue, and had a quiet conversation there with a man we called "Zingy." Zingy would take the money, record the lucky number -- a wife's birthday, a father's license plate -- then sell his loyal customer half a pound of mortadella and a package of Lucky Strikes. And the workingman would go home to his cluttered life in his drafty house and fall asleep clutching a tendril of a dream that he might "hit," that "the number" would come in for him and his family that one time, and then all the world's harsher edges would be rubbed smooth.

Of course, in Revere and elsewhere, one of the things that has changed in the last forty years is that the government has taken over Zingy's job. Now people walk down to a corner store and print out their lucky number on a blue-edged lottery form, and carry away the receipt (something that, after certain highly publicized arrests, Zingy stopped offering). But they go to sleep holding tight to the same dream. Only now, a portion of the profits goes to the state, to be spent by bureaucrats and politicians, whereas in earlier times the money went from the bookies upward -- or, more accurately, downward”to a handful of violent, sly men in smoky private clubs, to be spent on jewelry for their girlfriends and vacations in Las Vegas.

The bookmakers were the mob's menial laborers, though, and didn't have exotic girlfriends or take exotic trips. Without exception, the ones I knew were affable, modest men who had stumbled into their profession by accident, or taken it up as a second job, the way someone else might put in a few hours delivering lost airport luggage or standing the night watch at an office building. But they were part of the fabric of Revere, too.

Occasionally, the uglier side of that fabric was turned to the light. In the 1960s there was a turf war going on in Greater Boston among different factions of the underworld -- the Irish, the Jews, the various bands of Italians. This was closer to the movie version, to that brutal, hateful way of life modern moviegoers seem so attracted to -- as if it isn't quite real and could never affect them. We would be listening to the news in our kitchen at breakfast and hear that a body had been found in a nearby city, or in Revere, a mile or two miles away: in the trunk of a car, on a street corner, behind a liquor store. Shot once in the back of the head, never any witnesses. Whenever these reports were broadcast, my mother would turn the radio off. I remember her bare freckled arm reaching up to the windowsill and twisting the nickel-sized black dial on the transistor radio, as though she might keep that aspect of Revere from my father and me, and maybe from herself as well. As if protecting us from life's unpleasant truths was as simple as slicing away the mealy sections of an overripe cantaloupe and bringing to the table only the juicy golden heart of it. "That's not Revere," she would say. As if she were insisting, That is not cantaloupe; that part we scrape into the metal bowl and carry out to the garbage pail.

I understand why she did that. Like most of the people in Revere, she and my father went about their lives in a straightforward, honest fashion, and didn't much appreciate the fact that the Boston newspapers and TV stations gave so much attention to the mafia, and so little to the ordinary heroism of the household, the factory, and the street. I've inherited some of my parents' attitudes. I don't much appreciate the fact that, to this day, the Italian-American way of life has been reduced to a television cliché: thugs with pinkie rings slurping spaghetti and talking tough. My story has nothing to do with that cliché. Almost nothing.

But the mob was a part of Revere in those days; it's pointless to deny that. The Martoglios shouting at each other at the top of Hancock Street when I delivered the Revere Journal on Wednesday afternoons was part of Revere. The dog track, the horse track, the hard guys and losers in the bars behind the beach, the crooked deals worked out near City Hall, the lusts, hatreds, feuds, petty boasts -- it was all as much a part of that place as the neighbor who shoveled away the snow the city plow had left at the bottom of your driveway on the night of a storm, when you were off visiting your mother or sister or friend in the hospital; or the happy shouts of young families on the amusement rides; or my grandparents neighbor Rafaelo Losco, who once, in the middle of a conversation with my mother, when I was five or six years old, broke from his cherry tree a yard-long branch heavy with ripe fruit, and handed it across the back fence to me.

Though I sometimes want to, I cannot paint a place, or a family, or a life -- my place, my family, my life -- in the pretty hues of cheap jewelry. I can't give only one-half of the truth here, because what I want to say to my daughter is not: Life is a sweet cantaloupe, honey; smile and be glad, eat. But: Life can be bitter and unfair and mean, and most people rise part of the way above that, and some people transcend it completely and have enough strength left over to reach out a hand to someone else, light to light, goodness to good, and I grew up among people like that -- not in sentimental novels or on the movie screen, but in fact. They were imperfect people, who struggled to see the decency and hope in each other, and if I can be like them, even partly like them, I will, and so should you. A road across the territory between too extremes, a middle way -- that's what I want to offer her. Between denial on the one hand and despair on the other, between sappiness and cynicism. A plain road, across good land.

In Revere, In Those Days

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0375714057

- ISBN-13: 9780375714054