Excerpt

Excerpt

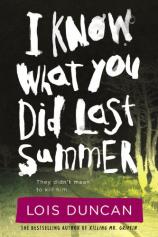

I Know What You Did Last Summer

The note was there, lying beside her plate when she came down to breakfast. Later, when she thought back, Julie would remember it. Small. Plain. Her name and address hand-lettered in stark black print across the front of the envelope.

At the time, however, she had eyes only for the other letter, long and white and official. Hurriedly, she picked this up and paused, glancing across the table at her mother who had just come in from the kitchen.

“It’s here,” Julie said.

“Well, aren’t you going to open it?” Mrs. James set the coffeepot down on its hot plate. “You’ve been waiting for this long enough. I would think you’d have had it open before you even sat down.”

“I guess I’m scared,” Julie admitted. She slipped her forefinger under the corner of the flap. “Okay. Here goes.” Running her finger the length of the envelope, she drew out the folded sheet of stationery and smoothed it flat on the table.

“Dear Ms. James,” she read aloud. “I am pleased to inform you that you have been accepted —”

“Oh, honey!” Her mother gave a little gasp of delight. “How wonderful!”

“Accepted!” Julie repeated. “Mom, can you believe it? I’m accepted! I’m going to Smith!”

Mrs. James came around the table and gave her daughter a warm hug.

‘‘I’m so proud of you, Julie, and your dad certainly would be too. If only he could have lived to have known about it, but — oh, there’s no sense in looking backward.” Her eyes were suspiciously bright. “Maybe he does know. I like to think so. And if not, I’m proud enough for the both of us.”

“I can’t believe it,” Julie said. “I honestly can’t. When I took those tests, I felt as though I was missing so many questions. I guess I knew more than I thought I did.”

“It’s your senior year that’s made this possible,” her mother said. “I’ve never seen such a change in anybody as in you this past year. The way you’ve buckled down and studied — you’ve been a completely different person. And, I’ll admit this now, it’s worried me a little.”

“Worried you?” Julie exclaimed in surprise. “I thought you always dreamed of my going to the same college you did. Last year you were on me all the time about being out too

much and never cracking a book and spending half my life at cheerleader practice.”

“I know. It’s just that I never expected you to do such an about-face. I can almost pinpoint the day it happened. It was just about the time you broke up with Ray.”

“Mom, I’ve told you —” Julie tried to keep her voice light despite the sudden shock of cold that hit her stomach. “Ray and I didn’t exactly break up. We just decided we were seeing too much of each other and we’d slow it down for a while. Then he left home and took off for the coast, and that took care of that.”

“But to give up dating so completely —”

“I haven’t,” Julie said impatiently. “I still go out some. In fact, Bud’s coming over tonight. That’s a date.”

“Yes, there’s Bud. But that’s only been recently, and it’s not the same. He’s older, more serious about everything. Of course, I’m happy and proud that you’ve put in enough work to get accepted by a good eastern college, but I wish you’d been able to balance it better. Somehow I have the feeling that you’ve missed a lot of the fun of your senior year.”

“Well, you can’t have it all,” Julie said. Her voice sounded high and sharp, even to her own ears. The cold feeling in her stomach was spreading higher, up where it touched her heart. She shoved back her chair and got up. ‘‘I’m going up to my room. I’ve got to find my history notes.”

“But you haven’t eaten,” Mrs. James exclaimed, gesturing toward the plate of scrambled eggs and toast, still untouched on the table.

‘‘I’m sorry,” Julie said. “I-I guess I’m too excited.” She could feel her mother’s worried gaze upon her as she left the table. Even after she was out of eyesight, the worry stayed with her as she climbed the stairs and went down the hall to her room.

Mom knows too much, she thought. She has this funny way of knowing more than you ever tell her.

“I’ve never seen such a changein anybody,” her mother had said. “I can almost pinpoint the day. . . .”

But you can’t , Julie told her silently. Not really. And you shouldn’t try. Please, Mom, you shouldn’t ever try.

She entered her bedroom and shoved the door shut. It closed with a sharp click, and her mother was left behind, back down in the breakfast room with the uneaten eggs and the coffeepot. The room closed protectively around her, a perfect room for a teenage girl who was pretty and loved and happy with herself, a girl who had never had a problem.

Her mother had had the room decorated for her a little over a year ago, on her sixteenth birthday. “We’ll have it done in any color you want,” she had said. “You can choose.”

“Pink,” Julie had said immediately. It was her favorite color, the one she wore most often, even though she had red hair. There was a pale pink T-shirt in the farthest corner of her closet, buried behind the other clothes. It had been new that night last summer. “You look like a rosebud with freckles,” Ray had teased her. The shirt looked great on her, but she had never worn it after that night. She would have given it away, if she had not been afraid that her mother might remember it sometime and ask what had become of it.

Now she seated herself on the end of her bed, drawing deep, slow breaths while the cold within her faded and her heart grew still.

This is dumb, Julie told herself firmly. It’s been almost a year since the thing happened. It’s over and done with, and I swore to myself I’d never think about it again. If I let myself get this uptight over some innocent little comment of Mom’s, I’ll wind up right back where I started, an absolute basket case.

Across from her in the oval mirror over the bureau another Julie looked back at her, pale and unsmiling. I have changed, she thought with mild surprise. The girl in the mirror bore little resemblance to last year’s Julie, bubbly, bouncy, sparkplug of the pep squad, the cheerleader with the smallest size and the biggest yell. This girl had shadows behind her eyes and a tightness about the mouth.

You’re going to Smith, Julie told herself. Just keep that in mind, will you? You’re getting out of here in only a couple of months. You won’t be going to the university, you’ll be going east, away from this town, and the road, and the picnic area above it. You won’t be running into Ray’s mother at the drugstore. You won’t see Barry on campus or Helen on television. You’ll be out — free! A new place, new people, new things to do and think about, a whole new set of things to remember.

She felt steadier now. Her breathing was slow again and even. She picked up the letter from Smith, which she had dropped on the bed beside her, and looked again at her name, neatly typed, on the official-looking envelope. She would take it to school with her, she decided; there were people there she could show it to. Not to any other students especially — there wasn’t anyone she was that close to this year — but Mr. Price, her English teacher, would be happy for her and Mrs. Busby, who taught American Studies. And tonight when Bud came over she would show it to him. He’d be impressed, and sorry, maybe, because she would be going away. Bud had been calling so often recently that it was possible he was getting more serious than he should be. It would be good for him to realize that this relationship wasn’t going to go anywhere, that it was just for now and in the fall she would be somewhere else.

There was a rap on the bedroom door.

“Julie?” her mother asked. “Are you keeping track of time, dear?”

“Yes. No . . . I guess I wasn’t.” Julie got up off the bed and opened the door. “I was just sitting here, gloating over the acceptance. Honestly, I’d just about given up hoping. It’s been so long since I applied.”

“I know,” Mrs. James said sympathetically. “And I didn’t mean to take the wind out of your sails by criticizing. I know how hard you’ve been working, and I’ve just been afraid you were overdoing it. I’m glad that now you can relax and enjoy your summer.”

‘‘I’m glad too,” Julie said.

She put her arms around her mother and gave her an impulsive hug. Her mother’s arms came back around her, surprised and glad.

I ought to hug her more often, Julie thought. I don’t deserve to have somebody like this for a mother. I love her so much, and I’m all she has since Daddy died. Now I’ll be going away and she’ll be alone, and still she’s happy for me.

“Are you sure you’ll be okay?” she asked against her mother’s soft cheek. “Can you get along, do you think, with me so far away?”

“Oh, I think so,” Mrs. James said with a catch in her voice that was supposed to pass for laughter. “I made out all right before you were born, didn’t I? I’ll keep busy. I’ve been thinking that maybe I’ll go back to work full time.”

“Would you like that?” Julie asked. Her mother had been a home economics teacher before her marriage, and since her husband’s death eight years ago, she had been working as a substitute.

“I think I would. It would be nice to have my own class again. With you out of the nest there won’t be anyone to need me at home, so it’s time to be needed somewhere else.”

“I did lose track of time,” Julie said apologetically. ‘‘I’d better get going.”

Her mother glanced at her watch. “You are late. Would you like for me to drive you?”

“That’s all right,” Julie told her. “I haven’t been late all year, so it won’t kill me to get a late slip today. And maybe I won’t. Mr. Price is a pretty nice guy about things like that.” She gathered up her books and history notes from the bedside table. Downstairs she paused long enough to rummage in the coin bowl on the sideboard for enough money to buy a Coke later.

‘‘I’ll see you after school,” she said. “Bud’s not picking me up till around eight, so there’s no reason we have to eat early. Are you going out anyplace?”

“I don’t have any plans,” Mrs. James said. “Wait a minute, honey. You didn’t get your letter.”

“Yes, I did. It’s here in my notebook.”

“No, I mean the other one.” Her mother leaned across the table to pick up the second envelope, half-concealed by the edge of the egg plate. “There were two pieces of mail for you this morning. Not that this could possibly be as exciting as the first one.”

“It’s the size of a party invitation, though I don’t know who would be inviting me to a party.” Julie took the small envelope from her mother’s hand. “That’s funny. It has big block printing and no return address.”

She tore the envelope open and removed a folded sheet of lined paper.

“Who is it from?” her mother called back over her shoulder as she carried the breakfast dishes into the kitchen. “Anybody I’ve ever heard of?”

“No,” Julie said. “Nobody you know.”

With slowly growing horror she stared at the letter, at the one black sentence that peered up at her from the smudged paper.

I’m going to be sick, she thought. Her legs felt weak, and she reached out and caught hold of the edge of the table to steady herself.

It’s a dream, she told herself hopefully. I’m not really awake and standing here in the dining room at all. I’m lying in bed upstairs, asleep, and this is only a nightmare like the ones I used to have back in the beginning. I’ll close my eyes, and when I open them I will wake up. It will be gone . . . the paper will be gone. It will never have been.

So she closed her eyes, and when she opened them again the paper was still there in her hand with the short sentence printed on it:

I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST SUMMER.

***

It was almost dusk when Barry Cox pulled out of the parking area behind the fraternity house and drove through the campus and then north on Madison to the Four Seasons Apartments.

It was a familiar drive; in fact, he sometimes said jokingly to his frat brothers that the car knew it so well that it could drive there by itself.

“Sure it won’t get confused?” they joked back. “It knows the way to a couple of other pads too.”

“It keeps them straight,” Barry told them smugly. “It’s got a GPS.”

It was true that Helen wasn’t the only girl Barry went out with, though he was pretty sure that he was the only guy she was seeing. Crazy too, because living where she did, in an apartment complex full of singles, and looking like a swimsuit model, and holding her showy job — well, there were bound to be plenty of werewolves howling under her window.

That was one reason he continued seeing her on a regular basis. He hadn’t planned to once high school was over. A college man had a wide territory, and there were some pretty hot girls on the University campus who would be easy to hook up with, no strings attached. Then, when Helen had been handed that job as Future Star, it had changed things. A guy would have to be nuts to throw over the Channel Five Promo Girl. Now as he pulled into the Four Seasons parking lot, he grinned to himself. Helen was doing all right for an eighteen-year- old who hadn’t even finished high school. His mother had gone through the ceiling when she learned about Helen’s dropping out at the end of her junior year. “It proves what I’ve said from the beginning,” she had told him. “A person is the result of her background. That girl isn’t your kind, Barry; I don’t understand how you ever started dating her.”

Which, of course, was part of the reason — he knew it would bug his mother. And then there were her looks. Helen was beauty queen material, and the fact was already beginning to pay off for her. Not many girls her age had their own apartments without even having to split the cost with a roommate. Helen’s older sister, Elsa, was still living at home, stashing away half her earnings as a cashier in a department store, hoping that maybe someday, in a year or so, she might be able to make the break and get her own little hole-in-the-wall. And here was Helen with her own car, trendy clothes, anything she wanted, and not a worry in the world.

So what had she been so upset about on the phone? That call had surprised him. Helen wasn’t like a lot of girls, always calling their boyfriends. She seldom even texted him unless there was a definite reason.

This time she hadn’t given one.

“I’ve got to see you,” she had said. “It’s important. Can you come over later when I get off work?”

“This afternoon? Heller, we were just out last night. You know this is closed week. I’ve got finals to study for.”

“I told you, it’s important.” There had been an edge to her voice, something that didn’t happen often with Helen. Usually if he told her something, she accepted it without question. “I wouldn’t call you like this if it wasn’t. You know that.”

“Can’t you tell me what it’s about?”

“No.” She had left it at that. Just a fl at no. He was intrigued in spite of himself. He did have exams to study for, and he had a date later for coffee with Ashley Something-or-other from the Tri-Delt house, but nothing that couldn’t be shoved over a little.

“Well, if we make it early,” he said. “Right after dinner.”

“That’s fine. The earlier the better.” She hadn’t asked him to eat with her, and he was just as glad. Those domestic evenings with Helen running around serving pot roast by candlelight were rough to handle. He knew what she was aiming for, and it wasn’t what he was aiming for, and the whole game was making him jittery.

‘‘I’m calling from the studio,” she said. “I’ve got a webcast to do in a couple of minutes. I’ll see you around seven then, okay?”

“Okay,” Barry had said.

The conversation had left him curious. So curious, in fact, that he hadn’t bothered to go to the dining hall for dinner. He had just stopped at a Wendy’s and picked up a couple of burgers and a Frosty. Now here it was, barely past six-thirty, and he was climbing out of his car and starting up the walk that led past the pool to the steps to the second-level apartments. The pool and the area around it were crowded. The spring evening was still pretty cool, but the pool itself was heated, and there were some polar bear types splashing around and plenty of pretty girls sitting high and dry in deck chairs, taking the first opportunity of the season to show off their figures in bikinis.

For a moment he stopped, just enjoying the view, a little surprised that Helen wasn’t among them. She had a figure that was better than the best of them, and she wasn’t one who minded displaying it.

“Hi,” called one of the girls, a shapely little brunette in a red and white halter and short shorts. “Are you looking for an apartment? There’s a vacancy on the second floor.”

“Nope,” Barry replied, giving her a measuring glance. “Not this year, anyway.”

Actually, he would have given anything to be able to live in a place like this, but it wasn’t his mother’s idea of something the old man should finance. He was damned lucky, when it came to that, just to have gotten into a frat house.

He went on around the pool and up the stairs, pausing to glance back at the brunette who had turned sideways in her chair and was still watching him. Then he went on down the upper deck and rapped on the door of Helen’s apartment. He had to wait a few minutes for his knock to be answered, something that seldom happened at Helen’s. Then the door opened and she was standing before him. She looked good, as always. Her honey-colored hair was pulled back from her face and held in place with a gold band, and her violet eyes were carefully shadowed and outlined to make them even lovelier. She was wearing pale blue pants and a silk blouse with a chunky crystal necklace at the throat; evidently she had not changed clothes since coming back from the studio.

“Good,” she said. “You’re early. I was hoping you might be.”

‘‘I’m glad I didn’t disappoint you.” Something was wrong, Barry decided. Something was decidedly strange; this wasn’t the way he was usually greeted. “What’s up, anyway?”

“Come on in,” Helen said. “We can’t talk here.”

He stepped through the doorway and knew instinctively that someone else was in the apartment. He glanced at Helen questioningly.

“Who’s here?”

“Julie. Julie James.”

“You’ve got to be kidding!” He followed Helen into the living room where the other girl was seated on the sofa. “Hi, Julie. Long time, no see. How is everything going?”

“Hello, Barry,” Julie said stiffly.

She wasn’t as cute as he remembered her, that was for certain. Not that she had ever been the beauty that Helen was, but she had always had enough sparkle so that the lack of real looks went unnoticed. Now that glow seemed to have faded. Her eyes looked huge in a face that was too small to hold them.

“Well, hi,” Barry said again. “It’s good to see you. I thought you’d kind of dropped us off your friend list.”

“I came here for a reason.” Julie’s eyes went past him to Helen. “You didn’t tell him?”

“No,” Helen said. “I thought you ought to be the one. It’s your letter.”

“What are you talking about?” Barry asked them impatiently.

“What’s the big secret?”

“It isn’t a secret,” Julie said shortly. She gestured toward a sheet of notebook paper that was lying on the coffee table.

For a moment Barry gazed at it unseeingly. Then the words took shape for him, and he felt his breath catch in his throat.

“Where did that come from?”

“It came in the mail this morning,” Julie told him. “It was just there, stuck in with a lot of other letters. There wasn’t any return address.”

“‘I know what you did —’ ” Barry began to read the statement aloud. “That’s crazy! Who would send you something like that?”

“I don’t know,” Julie said again. “It was just there.”

“Have you mentioned anything to anybody? Is there somebody who would know?”

“I haven’t said a thing.”

“Helen?” He glanced across at her. Her delicate, fineboned face looked as bewildered as Julie’s. “Nobody. I haven’t said a word to anybody either.”

“Well, neither have I. We made the pact, didn’t we? So there’s no way this has any meaning. It’s some joke, somebody taking a jab at Julie.”

They were silent a moment. Shouts and laughter drifted up from the swimming pool through the open window. For a fleeting second the brunette in the red and white shorts slid through Barry’s mind.

I wish I were out there, he thought, with a beer in one hand, just kidding around with the bunch of them. If there’s one thing I don’t need, it’s to deal with a scene like this .

“It must have been Ray,” he said. “There’s nobody else it could be. Ray wrote it as some kind of joke.”

“He wouldn’t,” Julie said. “You know he wouldn’t do that.”

“I don’t know anything of the kind. You dumped that guy pretty abruptly, you know. One day you two were an item and the next you didn’t even want to talk to him. This could be his way of getting back at you by shaking you up a little.”

“Ray wouldn’t do that. Besides,” she motioned toward the envelope that was lying beside the letter, “this was postmarked from here. The last card I had from Ray was sent from California.”

“No.” Helen spoke up suddenly. “Ray’s back in town. I saw him yesterday.”

“You did?” Julie turned to her in astonishment. “Where?”

“In that little deli across from the studio at lunch time. He was coming out as I went in. I almost didn’t recognize him, he’s changed so much. He’s real tan now and he’s grown a beard. Then I looked back, and he was looking back too, and it was definitely Ray. He held up his hand and kind of waved at me.”

“Then that’s who it must be,” Barry said. “Of all the sick tricks! The guy must have gone over the edge.”

“I don’t believe it,” Julie said decidedly. “I know Ray better than either of you, and he wouldn’t do a thing like this. He felt worse than any of us when . . . it happened. He wouldn’t make a joke of it this way.”

“I don’t think he would either,” agreed Helen. She reached over and turned the paper so that she could see it better. “Is there any other way someone could have found out? Maybe by tracing the car?”

“Not a chance,” Barry said. “Ray and I spent a whole day hammering the dent out of that fender. Then we painted the car and got rid of it the next weekend.”

“Julie, are you sure you haven’t said anything?” Helen asked her. “I know how close you are to your mother.”

“I told you, I didn’t,” Julie said. “And if I did tell Mom, do you think she’d mail me something like this?”

“No,” Helen admitted. “It’s just that there doesn’t seem to be any answer besides that. If none of us told, if it wasn’t the car —”

“Did it ever occur to the two of you,” Barry broke in, “that this note might be about something else entirely?”

“About something else?” Julie repeated blankly.

“It doesn’t actually say anything, does it?”

“It says, ‘I know what you did —’ ”

“So? Last summer was three months long, you know. You probably did plenty of things.”

“You know what it means.”

“No, I don’t, and neither do you. Maybe the person who wrote it doesn’t know either. Maybe it’s a joke. You know how kids are sometimes, making silly crank calls and writing notes to people and sending spam. So some kid decides to play a prank — he writes a dozen of these and sends them to strangers right out of the phone book. Do you think there’s a person in the world who, getting a message like this, couldn’t look back and think of something he did last summer that he wasn’t proud of?”

Julie digested the argument in silence. Then she said, ‘‘But we have an unlisted phone number.”

“Well, then, he found you some other way. Maybe it’s a nerd from school who has a thing for you and wants to get a reaction. Or some guy you pissed off because you wouldn’t go out with him, or the kid who packs bags at the grocery store. There are plenty of creeps in the world who get their kicks out of getting girls all shook up.”

“Barry’s right about that, Julie.” There was relief in Helen’s voice. ‘‘I’ve known some people like that myself. Why, you wouldn’t believe the phone calls you get when you work on television! There was one guy who used to call me, and he wouldn’t say a word. He’d just breathe. I was ready to go out of my mind. I’d answer the phone, thinking maybe it was Barry, and there would just be this heavy breathing in my ear.”

“Well,” Julie said slowly, “I suppose that’s possible. I-I never thought about something like that.”

“If the thing last summer hadn’t happened, if you’d gotten this note and there wasn’t something that came straight into your mind, you’d have thought about it, wouldn’t you?”

“Maybe. Yes, I guess I would have.” She drew a long breath.

“Do you really think that’s it? It’s just somebody’s idea of a joke?”

“Sure,” Barry told her firmly. “What else could it be? Look, if somebody did know something, he wouldn’t be writing silly notes, would he? He’d go to the police.”

“And it wouldn’t be now,” Helen said. “It would have been back last July when the thing actually happened. Why would anybody wait ten months to react?”

“I don’t know,” Julie said. “When you put it that way, it doesn’t sound likely.”

“It isn’t likely,” said Barry. “You’ve got yourself all tied up in knots over nothing. And, Heller, you’re just as bad, phoning me like that. You had me thinking something awful had happened.”

‘‘I’m sorry,” Helen said contritely. “Julie called me about it this afternoon, and I reacted the same way she did. We both panicked.”

“Well, un-panic,” Barry told her. He got to his feet. Helen’s lovely apartment, which always before had seemed so spacious and luxurious, was suddenly unbearably suffocating. “I’ve got to get going.”

“Why don’t you stay awhile?” Helen suggested. ‘‘I’ve got a whole hour and a half before I have to leave for the studio.”

“That’s an hour and a half that I don’t have. I told you this was a closed week and I have to study.” He turned to Julie. “Do you need a ride? I can drop you off at your house on my way back to the campus.”

“No, thanks,” Julie said. “I don’t need a ride. I’ve got Mom’s car.”

“Don’t you want to stay, Julie?” Helen asked her. “We haven’t talked for ages. There must be a lot for us to catch up on.”

“Another time, okay? I’ve got a date picking me up at eight.”

“Take it easy, then,” Barry said. “It was good seeing you.” He turned back to Helen.

‘‘I’ll be seeing you, Heller.”

“Do you want to plan on doing something Monday?” Helen suggested. “It’s Memorial Day, which usually means a party of some kind around this place.”

“It depends on how much studying I get done over the weekend. I’ll call you. I promise.”

She started to get up to walk him to the door, but he waved her back down. The last thing he felt like after this was an affectionate farewell scene with Julie as an audience.

He let himself out, leaving the two girls together, and went down the steps and back along the side of the pool. The underwater lights were on now, and the crowd of exhibitionists had thinned a little. The perpetual party that always started around the pool on Friday evenings had broken, as it generally did, into several smaller parties, most of which had moved upstairs into private apartments.

Gas lights flickered along the walkway, and the greenery in the planters rustled slightly in the faint evening breeze. Barry got into his car and turned the key in the ignition.

Somewhere in the parking lot another engine came to life. Sitting quiet, Barry let the motor idle. There was no movement that he could see among the rows of parked cars.

Coincidence, Barry told himself impatiently. I’m as uptight as those crazy girls .

He flicked on the headlights, threw the car into gear, and pulled out of the lot onto Madison Avenue. He drove slowly back to the campus, glancing occasionally into the rear view mirror.

There were lights behind him, but then it was early on a weekend evening, a time when streets were always busy with traffic. When he turned onto Campus Drive the car behind him turned as well, but when he slowed and pulled over to the curb, it went on past him without hesitation and disappeared around a curve at the end of the street.

Crazy, Barry repeated to himself. Why should I suddenly start thinking people are following me just because Julie James pushes the panic button? Like I told her, there are all kinds of creeps in the world. But he kept having the uneasy feeling that there was a pairof eyes boring into his back right between the shoulder bladeswhen he left the car in the lot and walked back across the lawnto the entrance of the frat house.

***

There was a car parked in front of the James’ house when Julie pulled into the driveway. Her first thought was that Bud had come early, but a second glance told her that this was not Bud’s cream-colored Dodge.

The front door of the house stood open, and through the screen voices floated to her as she crossed the lawn and mounted the steps to the front porch. One voice was her mother’s, lifted with unaccustomed gaiety.

The second voice stopped her. For a long moment Julie stood frozen, caught and held, unmoving. Then her mother, who was seated on the far side of the living room, facing the doorway, glanced up and saw her. “Julie, look who’s here! It’s Ray!”

Julie opened the screen and went into the room, drawing the solid door closed behind her.

“Hi,” she said a bit stiffly. “I saw the car outside but I didn’t recognize it.”

“It’s my dad’s,” Raymond Bronson said, getting to his feet. He stood there awkwardly, as though wondering what sort of greeting to offer. Then he held out his hand. “How are you, Jules?”

“Okay,” Julie said. “Fine.” She went forward and put her hand in his, holding it formally, then releasing it. It was a harder hand than she remembered. “I didn’t know you were back. Your last card was from the coast. You said you were working on some kind of fishing boat.”

“I was,” Ray said. “The guy who owns the boat has a kid who works with him in the summers. There wasn’t room for both of us.”

“That’s too bad,” Julie said, because she could think of nothing else to say.

“Not really. Jobs like that are on-again, off-again. I was about ready to come home for awhile anyway.” He was waiting for her to sit down, so she did. Not beside him on the sofa, but in the armchair facing him. He took his seat again. “Your mom’s been telling me about your getting your go-ahead from Smith. That’s great. You must really have been hitting the books.”

“She has,” Mrs. James said with pride. “You wouldn’t have known her this year, Ray. I don’t know whether it’s because you haven’t been here to keep her out half the night or whether she just suddenly decided to buckle down, but the results have been remarkable.”

“That’s great,” Ray said again.

Mrs. James rose. “I’ve got a cake waiting to be iced in the kitchen, and I know you kids have a lot of catching up to do. I’ll bring you out a piece when I get it done.”

“I can’t stay long,” Ray said.

“I have a date,” said Julie, “in just a few minutes.”

She didn’t meet his eyes when she said it, although she knew, of course, that he would probably expect her to have a date on a Friday night. He had undoubtedly done his own share of socializing out in California. She wondered what he would think of Bud. Bud was so far from the type of boy she had dated in school, so far from Ray’s type, though Ray himself had changed tremendously since she had last seen him. He looked older. He was very tan; his light hair grew thick and long down over his ears, and his brows were bleached pale over his cat-green eyes. As Helen had reported earlier, he had grown a beard. It was short and stubby and looked as though it belonged on somebody else’s face.

They sat in awkward silence after Mrs. James left the room.

Then they both spoke at once.

“It’s nice that you —” Julie began, and Ray said, “I just thought —” They both stopped speaking. Then Julie said carefully, “It’s nice that you came by.”

“I thought I’d say hello,” said Ray. “I’ve thought about you a lot. I-I just wanted to see how you were.”

“I’m fine,” Julie repeated, and the green eyes that knew her so well, that had seen her through so many situations — through parties and picnics and cheerleading tryouts, and being caught cheating on a math test, and coming down with a rare case of the chicken pox right before the Homecoming — those eyes kept looking in disbelief.

“You don’t look fine,” Ray said. “You look like hell. Has it been dragging on you like this ever since?”

“No,” Julie said. “I don’t think about it.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“I don’t,” Julie told him. “I don’t let myself.” She lowered her voice. “I made up my mind right after the funeral. I knew if I kept thinking . . . well, what good would that have done?

People go crazy dwelling on things they can’t change.” She paused. “I sent him flowers.”

Ray looked surprised. “You did?”

“I went down to People’s Flower Shoppe and bought some yellow roses. I had them delivered without my name on them. I know it was silly. It couldn’t help. It was just . . . I felt I had to do something and I couldn’t think of anything else.”

“I know,” Ray said. “I felt the same way. I didn’t think about sending flowers. I kept waking up at night and seeing that curve in the road again, that bicycle coming up suddenly out of the dark like that, and I’d feel the thud and then the bump as the wheels went over it. I’d lie there and shake.”

“That’s why you went away.” It was a statement, not a question.

“Isn’t that why you’re going to Smith? To get away from here? You’ve never cared that much about college. You used to talk about maybe taking computer courses or something right here in town while I went to the university. Going east to school was the last thing you had on your mind.”

“Barry’s at the U now,” Julie said. “He’s on the football team.”

“I saw Helen yesterday at lunch. She looked pretty.”

“She’s a Future Star,” Julie said. “Did you know? Channel Five had this beauty contest thing based on photographs, and Helen won it. She’s got a full-time job representing the station for all kinds of things, giving spot announcements and small news reports. She even deejays her own webcast in the afternoons.”

“Great,” Ray said. “Are they still solid?”

“I guess so. I saw them today.” Julie shook her head. “I don’t know how Helen can do it — keep going with him, I mean. She was there, she saw him that night, she heard the things he said. How can she still think he’s so wonderful? How can she even stand to have him touch her?”

“It was an accident,” Ray reminded her. “God knows, Barry didn’t plan it. It could have been me driving the car. It would have been if I hadn’t won the toss for the back seat.”

“But you would have stopped,” Julie said.

There was a long silence as the words hung there between them.

“Would I?” Ray asked at last.

“Of course,” Julie said sharply. And then, “Wouldn’t you?”

“Who knows?” Ray shrugged his shoulders. “I tell myself I would have. You think I would have. But how can we know? How can you know how anybody’s going to react in a situation like that? We’d all had a few beers and smoked a little pot. It happened so fast.”

“You called for the ambulance. You wanted to go back.”

“But I didn’t insist on it. You wanted to go back too, but we didn’t. We let Barry talk us into the pact. I could have held out, but I didn’t. I must have wanted to be talked into it. I’m no better than Barry, Jules, so don’t try to make him the black knight and me the prince on the white horse. It just isn’t that way.”

“You’re as bad as Helen,” Julie said. “The both of you! You form the Great Society for Admiring Barry Cox. You’d stick up for him, no matter what he did. You should have heard her tonight, begging him to call her this weekend, and here they are, supposedly a couple. It’s just so degrading.”

“I don’t see anything degrading about sticking by your guy if you care about him.” Ray’s brows drew together in that quizzical look she knew so well. “What were you doing at Helen’s anyway? I thought you’d burned all your bridges, that you were cutting ties with all of us.”

“I have,” Julie told him. “That is, I meant to. Today I got a letter in the mail. It upset me and I called Helen, and then she called Barry, and suddenly there we all were, hashing it over. I wish now I’d just chucked it and not made such a big deal about it.”

Ray looked interested. “What sort of letter?”

“Just a prank thing. Helen says she gets them sometimes and phone calls and e-mail too, but I never got any before, so I overreacted.” She opened her purse and fi shed out the envelope.

“Here it is, if you want to see it.”

Ray got up and came over and sat on the arm of her chair, taking the letter out of her hand. He opened it and read it.

“Barry thinks it was written by some kid,” Julie said. “That it doesn’t really mean anything, it just happened to have hit on something that struck a nerve.” She paused, watching his face as he studied the black line of printing. “Is that what you think?”

“It’s possible,” Ray said, “but it’s one hell of a coincidence. Why pick on you? Do you know anybody who could have sent it?”

“Barry thought maybe some boy from school.”

“You said you’re dating.” He raised his eyes from the paper.

“This guy you’re going out with tonight, is he the practical joker type?”

“As far from it as you can get,” said Julie. “Bud’s a nice guy. Older. Serious about everything. He was in the Army and fought in Iraq. The last thing he’d ever do is write silly notes.”

“Are you in love with him?” The question was so sudden, so far away from the previous discussion, that she was unprepared.

“No,” she said.

“But he is with you?”

“I don’t think so. Maybe a little. Please, Ray, this is just a nice guy I met one day in the library. He asked me out and Mom had been bugging me about never going anywhere anymore, so I went. And then it was easy just to keep on. Besides, what difference does it make to you? You and I — we’re not a thing anymore.”

“Aren’t we?” He reached out a hand and placed it gently under her chin, tilting her face up so that it was raised to his. The face that looked down at her was familiar, darker and stronger than she remembered it, framed with shaggy hair and a beard. But the eyes were the same. No stranger could ever look at her through Ray’s green eyes.

“It’s still there,” he said. “You know it is. You could feel it, just the way I could, the moment you walked into the room. We had too good a thing for too long. We can’t just let it go.”

“That’s how it has to be,” Julie said. “I mean it, Ray. I really do. It’s the only way we’ll ever forget. I’m going to leave here, leave all the people and places connected with that dreadful night, and never look back. It’s over and done with. There’s no repairing it. So I’m going to erase it.”

“And you think that’s possible?” His voice was sad. “Sweetie, something like that doesn’t get erased. I thought maybe it could be too, there in the beginning. That’s why I packed up and took off. New places, new people . . . I thought that would do it. But it didn’t. You can’t run away. You at Smith, me out in California, it’s still there with us. I realized that fi ally. It’s why I came home.”

“If you can’t run away,” Julie said chokingly, “what can you do?”

“Face up to it.”

“You mean, break the pact?”

“No,” Ray said. “We can’t do that. But we can talk to the others. We can dissolve the pact, if we’re all in agreement.”

“Never. Barry will never agree to it, and if he won’t, Helen won’t.”

The doorbell rang.

Ray’s hand dropped to his side. He got up from the arm of her chair. “That must be your friend.”

“I guess so. He was picking me up at eight.” Julie’s eyes went nervously from Ray’s face to the door.

“Don’t worry, I’ll behave myself. I’ll probably even like him. He’s got good taste in girls, anyway.”

They went to the door together, and Julie introduced them.

Bud said, “Raymond Bronson? You any relation to Booter Bronson who runs the sporting goods store?”

“His son,” Ray told him. “I hear you just got back from Iraq. I sure don’t envy you that gig.”

They shook hands civilly and stood and talked a few moments in a pleasant fashion, as though they might have been friends if given the chance. Then Ray left, and Julie excused herself and went upstairs to comb her hair.

When she came down, Bud was still standing there by the door as he had been when she left him. He looked up at her and smiled as she came down the stairs, and for an instant she felt like crying because his smile was such a nice one and because his eyes weren’t green.

Excerpted from I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST SUMMER © Copyright 2010 by Lois Duncan. Reprinted with permission by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. All rights reserved.

I Know What You Did Last Summer

- Genres: Horror

- paperback: 224 pages

- Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-10: 031609899X

- ISBN-13: 9780316098991