Excerpt

Excerpt

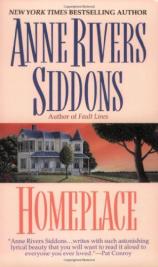

Homeplace

Even before she opened her eyes, the child was afraid. Coming out of sleep, she was not sure where she was, only that it was wrong. She should not be in this place. He would be very angry. She was eight years old, and she had been afraid of him all of her life.

She lay still and listened, and heard the rain. The rain came riding on a vast gray wind, to pepper the flat tin roof and sing in the tops of the black-green pines in the woods across the road from the cabin. Over it, much nearer at hand, she heard the chink of the iron poker in the cooling fireplace, and the visceral, thumping wail of the Atlanta jigaboo station on the radio Rusky had given J. W. for Christmas.

Without opening her eyes, the child burrowed her head under the flaccid feather pillow and dragged the quilt closer around her. Her body was warm in the piled nest of quilts and blankets Rusky had heaped over her during the night, but her feet were icy and her nightgown must be up around her neck, because her legs were cold up to her thighs. She took a deep breath, inhaling musty bedclothes and the ashy, dark smell the cabin always had, made up of smoke from the fireplace and the smell of Rusky and J. W. themselves. It was not sweat, though that was part of it, it was more, was the fecund essence of the Cromies, who lived in the sagging cabin behind the big house on Pomeroy Street. It was a rich smell, deep and complicated, somehow very old, the essence of all Negroes Mike had ever known.

"Why do Nigras smell like ashes?" she had asked Rusky once.

"'Cause dey spends so much time tendin' to white folkses' fires," Rusky said, thumping the iron down on the ironing board in the big, square, sweet-steamed kitchen. "And 'cause de Lord give 'em that smell, same as he give you a smell like a new li'l ol' puppy. Kindly of sweet and sour at the same time. It ain't polite to ax folks why they smells like they does, Mike. It hurts they feelings."

"Are your feelings hurt?"

"Naw, but I'm yo' family. Don't you go axin' nobody outside yo' family why they smells like they does. "

"Why are you my family if you're black and I'm white?"

"Go on, now, I got to finish this arnin' and get on to them beans, or ain't none of you gon' get any supper. You just axin' questions to hear yourself talk. "

The child's name was Micah Winship. She did not want to open her eyes, to lose the cocoon of the bed and the covers. She drifted for a space of time, her legs and feet drawn up to her body, willing Rusky to remain silent, but she did not.

"Git up, Mike. Time to go over yonder an' start breakfast. You know you daddy don't know you over here.

"I don't want to get up."

"I don't care what you wants. You really be in a fix if he come back from his walk an' fin' you over here with me. I promise him the las' time I ain't gon' bring you home with me no more. He like to fire me if he catch you sleepin' over here with me, an' then what you all gon' do?"

"I don't care. I'm not going to get up.

"You promise me las' night after that nightmare an' all that hollerin' you doin' that you get up when I call you if I let you come home with me. Big girl like you, in the third grade, yellin' an' hollerin' like that. Git up, now. Move yo' self."

"I don't have to. You can't make me."

"Well, I know somebody what can make you, an' right quick, too. Come on, J. W. We gon' go tell Mr. John Mike over here in the baid an' we cain't git her out."

"Aw, Mama . . . " J. W. said from the shed room off the cabin's main room, where he slept winter and summer.

"I'm gon' out dis door, Mike, J. W.," Rusky said, and slammed it to emphasize her words.

"Wait!" Mike shrieked, jumping out of the cocoon of covers and rummaging blindly for her blue jeans and sweater. Fear leaped like brush fire. "Wait for me, Rusky! I'm coming . . . don't tell him!"

"Don't tell who what?" said Derek Blessing, and Mike awoke finally and abruptly, and sat up in the great bed in Derek's crow's nest of a bedroom atop the beach house on Potato Road, in Sagaponack, Long Island. Rain on a tin roof and the sough of the wind in the sweet pines of Lytton, Georgia, became the residual spatter of the sullen, departing northeaster and the boom of the surf on the beach, and the acid smell of Rusky Cromie's moribund fire became the first breath of the resurrected one in Derek's freestanding Swedish fireplace. J.W.'s radioed Little Richard became Bruce Springsteen. She looked around her. She was naked in the bed, with the ridiculous mink throw trailing across her and onto the floor, leaving her feet and legs bare to the cold air flooding in from the open sliding glass doors facing the heaving pewter sea. Her heart was still hammering with the now-familiar slow, dragging tattoo of the past two days, and her mouth tasted foul and metallic from the unaccustomed tranquilizer and the congnac they had drunk last night. The snifter still sat, half full, on the table beside her, and the sweet, cloying fumes sickened her slightly. She cleared her dry, edged throat and combed her hair back with cold fingers. She squinted up at Derek Blessing, who sat down on the bed with a proffered mug of coffee. It smelt only slightly better than the cognac, probably because of the cinnamon Derek ground into it, an affection he had picked up somewhere on his latest promotional tour for Broken Ties.

Homeplace

- Mass Market Paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: HarperTorch

- ISBN-10: 006101141X

- ISBN-13: 9780061011412