Excerpt

Excerpt

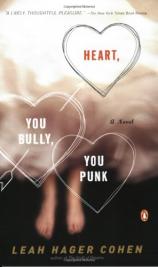

Heart, You Bully, You Punk

Says Esker, "I'll do it," when Ann James winds up with casts on both legs and needs home tutoring. She says it resignedly, as if, being department chair, only she might be expected to assume this extra burden; she also says it pre-emptively, denying the other two math teachers an opportunity to volunteer. Either of them might; what with open classrooms and team teaching, no one instructor is more responsible for a particular student than another. And Ann James is the sort of student any teacher might volunteer to tutor at home, even if she weren't also gifted in math. Esker can tell by the look on his face that Larry might like to; there go his sandy eyebrows tilting toward each other in an offering sort of way.But Rhada, the quicker, speaks first. "No, me. I'll do it." And Esker feels a flare of annoyance until Rhada adds, "That's time and a half for overtime, right?," making obvious to Esker what she ordinarily would have realized immediately, that Rhada's being sarcastic, of course. Esker moves briskly to the next item (the lack of a single freshman on Math Team), and the matter remains settled.

The radiator in the math office makes slurpy, digestive noises, and the narrow window (whose other half belongs to the science office, behind the particleboard partition) grows reflective with early dusk. Esker, never a lingerer, progresses with her usual efficiency through the agenda, adjourning just before five. Then, amid brief, amiable bustle-Larry stuffing algebra quizzes into his nylon briefcase, Rhada sliding mustard-stockinged feet into black chunk-heeled boots-the subject of Ann James returns.

"How long is she going to be out, do they know?" asks Larry. It happened last Friday; this is Monday. Word of the accident has gotten round, but few details.

Esker peers at the memo Florence, the headmistress, left in her box this morning. "Through the holiday, it sounds like."

"Poor kid."

"But, really, home tutoring?" says Rhada. "What happened to Florence's boundary issues?"

"What do you mean?" Larry zips his bag shut.

"You know." She strikes a pose, hand on hip, high-pitched attitude. Rhada is young, only three years out of Hunter College and still at the clubs every weekend. "All that 'no student-staff socializing' she's always going on about."

Esker, listening at her desk, keeps her eyes on paperwork. A hefty series of memos and policy statements, clarifications and initiatives, all that sort of thing, did clog their faculty mailboxes for a while when Florence came on as headmistress last year, but Esker suspects Rhada was spoken to individually as well. Sort of abruptly in October, she stopped hanging out on the building's wide front stoop with the hip-hop kids during lunch.

"Well," says Larry, considering. "Still, I guess she wants to please the customers."

"The customers!" Rhada makes a derisive sound as she slides her coat off the hanger. It is burnt-orange and has a hood rimmed in burnt-orange fake fur. "How'd Ann do it anyway, anybody hear?" Esker shakes her head; the note, in Florence's aggressively professional cadences, only says something about a bilateral fracture incurred on school grounds.

Larry says, "Fell off the bleachers, apparently," and Rhada says, "Ouch. Ow. Jeez," and leaves, characteristically abrupt. Esker is glad to have it end at that; she's aware of feeling an unaccountable protectiveness-no, possessiveness-around the subject.

Larry slings on his embarrassing leather jacket-too tough for his wispy blondness-and says to wish Ann a speedy recovery. He doesn't close the door behind him, and Esker listens to the clomp of his boots on the stairs, his pace as headlong and galumphing as a student's. Then, in the empty office, she smooths the headmistress's note and dials the number given.

"Hello?" Ann answers, sounding as if she were expecting the punchline to a joke.

"Ann? Esker from The Prospect School here." Teachers at The Prospect School are generally known by first name to students and colleagues alike, but Esker only ever goes by her last. Her first and middle names are Iphigenia and Julia, which she long ago found too preposterously romantic to use. On forms she is I. J. Esker.

"Oh. Hey!"

"You sound too chipper to've broken both ankles. How are you feeling?"

"Not my ankles," says Ann, "my heels," and, with some boastfulness, "I have bilateral calcaneal fractures. And I'm not really chipper. I'm on drugs."

"Oh."

"They gave me codeine. I feel excellent."

Esker smiles a smile located mostly in the movement of her throat and speaks crisply into the receiver. "I'm calling to arrange a tutoring plan for you while you're out. Your father, I guess, spoke with Florence."

"Yeah. He's not home right now."

"Would you like me to call back and speak with him?"

"No, that's all right. I can. What's the plan?"

"The plan," says Esker, "so far as I know, is to set up a time for me to come over and help you stay caught up with your math work."

"Okay."

"What would be a good day for you?"

"Any. I'm not exactly going anywhere." Ann is the sort of student who, codeine or no, speaks to a teacher with the same frank confidence as she would a peer. There is something unwittingly flirtatious in this. They agree on the following afternoon. Esker copies Ann's address into her engagement book with green pencil. Then she hangs up and gets her coat.

It is December already. No snow yet, but a cold vagueness hangs in the air, fumes of things burning, thinks Esker as she stands for a moment tying her scarf under the spread iron wings of the beast of indeterminate species that hovers over the school entrance. Some kind of predator, with its hooked beak and claw feet; Esker finds it macabre. She hurries toward Grand Army Plaza, weaving in and out of the flow of other pedestrians, dodging a stooped woman towing a metal cart of groceries. Her train is already there when she reaches the platform. Esker slips in, claims with efficiency the last empty seat. She's been making this commute for nine years.

The Prospect School is a small alternative high school housed off Prospect Park in a beguiling and dilapidated formerly private estate. The elaborately mosaicked floor in the lobby is minus a large portion of its intricate marble tesserae; the crystal chandelier hangs too high for anyone to bother replacing the burnt-out bulbs; the basement classrooms not only stink of mildew but sport bluish-greenish pointillistic growths on their walls; tiny mounds of fine, crumbled plaster collect in the coffin turns and on the wainscoting and the sills; and on and on; the Renovation Committee, inaugurated by Florence, compiled an exhaustive list last spring for fund-raising purposes.

Most of the 180-odd students come from Park Slope or Brooklyn Heights; most of the faculty do not. Esker finds teaching at The Prospect School to be rewarding in almost every way but monetary. She rents an apartment in lower Manhattan, on an anonymous block of Greenwich Street. The building is unusually old and tiny: three stories high and only thirteen feet wide; its immediate neighbors are warehouses, garages, and a nameless corner bar with a slow-blinking neon shamrock hung over the entrance. She's lived in the same apartment since she began teaching at age twenty-two. She doesn't remember when she ceased thinking of it as a temporary abode.

She'd moved in on a miserable dog-breathy day in August. Each crate and carton she'd lifted from the whitish van had seemed twice its weight: the very force of gravity that day had seemed unnatural, heavy as grief, and she lay, afterward, as if pinned to the bare mattress, damp-skinned, dry-eyed, taking in the ceiling. It was a splendid ceiling, actually, tin, stamped with a pineapple-y box design, and as evening sifted gradually into the room, the heaviness lifted and the shadows went bluish and soft. Esker rose then and walked two blocks west to the river, the breeze sweeping along her muscles, which were still shaky from exertion. She had drifted, a porous, untethered body, between the West Side Highway and the chain-link fence that ran along the docks, where the soft figures of coupling men moved together and apart in darkening indistinguishability. Radiant heat came at her from the asphalt, and headlights careened behind her back, and in her exquisite insignificance she'd found a measure of freedom that was almost like peace.

Esker gets off now at Chambers Street, ten blocks from home, and ascends into a light, cold rain. She puts on her hat. Taxis beckon along the avenue; she passes them by. Mastery over her own unhappiness has given her a clean, forceful gait.

Heart, You Bully, You Punk

- paperback: 224 pages

- Publisher: Penguin (Non-Classics)

- ISBN-10: 0142004324

- ISBN-13: 9780142004326