Excerpt

Excerpt

Harpsong

Sharon

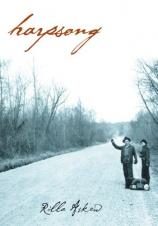

That’s me and him standing at the side of the road outside Joplin, Missouri. To look at it you wouldn’t know where it was, would you? Dirt road, bare trees, it could be anywhere, Arkansas or Mississippi, these Oklahoma hills even, where we came from. You wouldn’t know what year either, but I can tell you. 1935. I believe it was March maybe. The trees were just fixing to bud. The lady that took it posed us to look like that, like we were hitchhiking, which we weren’t, though we did do a lot of hitching. We rode the rails too, especially at first. That valise in the dirt wasn’t ours. Me and Harlan used a rucksack. The lady drove us in her car to that spot and got that valise out of her turtlehull and set it on the ground between us before she took the picture. It’s the only picture ever taken of me and Harlan, so far as I know.

I didn’t know about that one, or I didn’t know it was a public picture, till I ran across it in a postcard rack in Tahlequah way up after the end of the war. I about fainted. I felt like I was watching an old dream come alive in front of my face. I bought it so quick, like somebody might snatch it, but for the life of me I couldn’t recollect when it was taken. My hat there’s what caused me to finally remember. I’d found that cloth hat in a bar ditch near Joplin and lost it to the wind outside McAlester, so I knew right when the picture had to have been taken, and then I remembered the lady.

She came and picked us out of all the other folks camped under that railroad overpass, she walked right past women and their little kids and men with sores on their feet, which, if she meant to be taking pictures of poor people, like she said, you’d think she might have picked one of them. We were sitting in the shade underneath a girder, Harlan wasn’t playing his harp or anything, but that lady made a bee-line right for us, and really, I don’t know why, unless it was just because my husband was so pretty. He didn’t like anybody to say it, of course, he acted like that was such an embarrassment, but you’d seldom catch him smiling with his mouth open to show where his tooth was broke. See it there? She caught him with his lips open. You can’t tell if he’s grinning or squinting, but Harlan kept his lips shut tight over that chipped tooth most the time, except when he was singing or talking.

I cherish this picture anyway, even if it does feel like the lady stole it. She didn’t really, I guess. She told us what she was doing, and we stood right there, still as still, while she took our picture with a big black box camera. It wasn’t like she snuck around. She drove us back to the camp after and dropped us off, we never saw or heard from her again. Come to find out, she put that picture in a book along with a bunch of others. I didn’t know you could do that, take somebody’s picture and put it in a book or on a postcard and never ask them. But she paid us two dollars and a half, or she didn’t call it pay, she just gave it to us, said, “Here, get y’all something to eat.” We left for Oklahoma the next morning.

There’s another thing about this picture. I was with child then. I didn’t know it at the time, or my mind didn’t, but if you look at my face, staring off at the side of the road like that, you can see how I’m looking inward and outward at the same time, so some part of me must have known. So really, if I think about it, this is the only picture in existence of me and Ronnie and his daddy. That’s another reason I love it. I don’t care if a hundred thousand people see it, this picture is mine. My own and only, now. Oh, people act like they know everything, they tell all sorts of stories, don’t none of them know the real truth. They don’t. Me here, Sharon, his wife. I’m the one that knows Harlan.

I was fourteen years old the first time I laid eyes on him. He come walking out the road from Cookson on a hot May morning the week after school was out, 1931. It was a Saturday. My daddy was gone preaching. I was supposed to be sweeping the yard but what I was doing mostly was watching for Marie Tingle. She was a neighbor girl who sold Cloverine salve and delivered our GRIT once a week, and she rode an old white dray horse that mudged along slow as cream rising. I’d drag that shoemake broom through the dirt, weave a pattern out to the yard fence, and then I’d stand a while, looking. I aimed to be the first one at the gate when Marie got there, because if Mama saw her first, she’d come grab that magazine and put it away till we got the work done. Then she’d go off by herself to read the story, and the day would be half gone before I’d get my chance to read the next chapter. The GRIT ran a love story that went week to week, I was real anxious to find out what came next, I remember.

I seen him coming, I thought at first it was only the dust stirring, and then I thought it was a drunkard lolling, he had that rolling slap-footed gait, you know. I forgot all about Marie Tingle. I dropped the broom and ran up on the porch hollering, “Mama! Mama!” All five kids came tumbling out the door, and Mama right behind them. The dogs were barking a racket. Harlan kept coming along, he stopped outside the fence and said howdy, and then he stood there, peering up at us, smiling. Mama called the dogs off, they slunk back under the house, and after that it was just the sound of the locusts. Well, nobody was surprised to see a stranger in the road in those days, even if you lived a mile out from town, like we did, but Mama gawked at Harlan the way a calf looks at a new gate. He was all dressed up like he was set to go someplace. Believe me there wasn’t anywhere to go around Cookson, Oklahoma, that would justify a tie and a snap-brim hat, but that’s not what Mama was staring at anyway. She was looking at his face.

Oh, I can’t describe it, you can see for yourself. What that picture don’t show though is the color of his eyes, they were the prettiest light green. It don’t show how smooth his skin was, just practically like he was covered in doeskin. You can’t even see how long and black his eyelashes were, or how they curled up. Pretty. I’ll bet that was the very word in my mama’s mind. It was sure enough in mine. He asked for a drink of water, and Mama said, “Sharon, honey, go draw him some water.”

I blinked at her. My mama never called me honey. She motioned for him to come inside the fence and have a seat on the busted crate in the shade of an old bordark tree we had in the yard there. I felt Harlan’s eyes on me, I went to the well and drew the bucket, handed him the dipper. We were only a few feet from each other, out in the bright sun --- he didn’t go to the shade and he didn’t sit down - but I wouldn’t glance at him any more until I got back on the porch. His hat was pushed to the back of his head. He thanked Mama for the water, commented on the heat and so forth, but he kept flicking his eyes my direction. Mama stepped to the porch ledge, hoisted Ellie Renee on her hip, said, “I suppose you’re hunting a hand-out.” She didn’t appear nearly as suspicious as the words sounded.

“No, ma’am,” Harlan said, “don’t reckon I am. Wouldn’t mind if you had a little job of work a fellow could do, though.”

“What kind?” Mama said. I turned my whole head to stare at her. I’d never heard her say anything but move on down the road to a hobo.

“Any kind, ma’am. I can do about anything on a place needs doing.”

“I ain’t got any money to pay you.”

Harlan laughed. “Ain’t nobody got any money, near as I can tell. No place I been.”

“Where-all have you been?” Mama asked. She was shading her eyes with her free hand, but I saw her slip her other hand back to smooth her hair behind her ears.

“All over the country, ma’am.” Harlan cut his eyes at me. “Here to California and back,” he said. “Down to Texas, east as far as Georgia. Hadn’t been to Washington DC yet, but I’m goin’. Maybe in Washington somebody’s got some money.”

“Sounds like you been doing some hard traveling.”

“I have that, ma’am.”

“Well,” Mama said. The yard got so quiet, except for the insects. Even the twins were hushed, staring out from behind Mama’s skirt, Leonard had his fist wrapped in the cotton, sucking it in his mouth. I could see the baby moving up and down with Mama’s breathing. She was about two then, I guess, Ellie Renee. She was the blondest of any of us, had the finest hair, it feathered out in wisps all around her head like little fish fins. Mama kept reaching up to wipe her dirty cheek, rubbing over and over till Ellie started squirming, and then whining, and finally squalling, and then it wasn’t quiet no more.

Mama said over Ellie’s squalls, “You might bust me up some stovewood if you want. I could probably feed you a bite. The ax is yonder.” She nodded at the double-bitted chopping ax stuck in the tree stump.

“Ma’am, if I could get that bite to eat first, I could sure work better. I’ll even sing you a song for a bonus. Singer’s my name anyhow, like the sewing machine. I don’t sew but I do-si-do every chance I get.” Harlan folded his arms and cut a gawky little square-dance step in the yard. Mama tried to frown, but her face wouldn’t let her.

“Well. Come on then,” she said.

Harlan started across the yard, and I saw it again, how awkward he walked. Ellie kept squalling in Mama’s arms. Harlan stopped, whipped a harmonica out of his pocket and ran a trill up and down. The baby hushed and stared. The other kids peeked out from behind Mama’s skirt, the busted ladderback, the old canning crate, where they were all hiding.

“Have a seat,” Mama said. Harlan ran one last trill, moved to sit on the steps. “Sharon,” Mama said, “go fix Mr. Singer a plate.”

Well, there wasn’t a plate of anything in our house to fix, only cold biscuits left over from breakfast, which me and Mama both knew, but that wasn’t what had me caught. I was watching Harlan, how he held onto the banister while he swung himself down. His left leg flopped to the side like he couldn’t control it. My stomach dropped. The only person I knew with a leg that wouldn’t work right was the mail carrier Max Stunke, and that was because his was wooden. I thought that was what was wrong with Harlan’s.

“Sharon Earlene,” Mama said, “go in the house and fix Mr. Singer a plate of biscuits.”

I slammed in the house and poured about a pint of sorghum on those cold biscuits, and you know sorghum molasses was just nearly liquid gold to me, even if our daddy did own a sorghum mill and got paid with syrup for grinding other folks’ cane. Seemed to me like I just never could get enough of it. But I slathered those three biscuits like a punishment, like I was going to punish the stranger on the porch with too much of the thing I loved best, because in those few minutes he’d went from being perfect to awkward to one-legged. That’s what I thought..

I came back outside. Harlan had his harp making every kind of sound in the world, a train and a laying hen and a hoot owl and a jaybird, and the kids were jumping up and down and clapping, and the rooster was all puffed up on the chopping stump, crowing, and even Mama was leaning against a porch post, smiling. I set the plate on the top step and Harlan turned to me. He still had his lips wrapped around the harmonica, but he kept his eyes on my face. He nodded. My stomach went hot, my chest runny, like syrup on the stove, melted and running down. I forgot all about his crippled leg. I mean that. It was like I couldn’t see it anymore, even when he stood up afterwhile and went slap-footed across the yard to split a few licks of kindling.

Harpsong

- hardcover: 256 pages

- Publisher: University of Oklahoma Press

- ISBN-10: 0806138238

- ISBN-13: 9780806138237