Excerpt

Excerpt

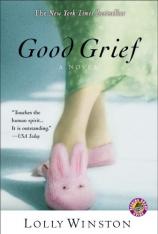

Good Grief

DENIAL

1

How can I be a widow? Widows wear horn-rimmed glasses and cardigan sweaters that smell like mothballs and have crepe-paper skin and names like Gladys or Midge and meet with their other widow friends once a week to play pinochle. I'm only thirty-six. I just got used to the idea of being married, only test-drove the words my husband for three years: My husband and I, my husband and I...after all that time being single!

As we go around the room introducing ourselves at the grief group, my heart drums in my chest. No wonder people fear public speaking more than death or heights or spiders. I rehearse a few lines in my head:

My name is Sophie and I live in San Jose and my husband died. No. My name is Sophie and my husband passed away of Hodgkin's disease, which is a type of cancer young adults get. Oh, but they probably already know that. This group seems up on its diseases.

A silver-haired man whose wife also died of cancer says that now when he gets up in the morning he doesn't have to poach his wife's egg or run her bath, and he doesn't see the point in getting out of bed. He weeps without making a sound, tears quivering in his eyes, then escaping down his unshaven cheeks. He looks at the floor and kneads his sweater in his hands, which are pink and spotted like luncheon meat.

We sit in a circle of folding chairs in a conference room at the hospital, everyone sipping coffee out of Styrofoam cups and hugging their coats in their laps. Fluorescent lights buzz overhead. They are bright and cruel, exposing the group's despair: the puffy faces, circles under the eyes like bruised fruit, dampened spirits that no longer want to sing along with the radio. There should be a rule for grief groups: forty-watt bulbs only.

The social worker who leads the group balances a clipboard on her knees and takes notes. She has one tooth that is grayer than the others, like an off-color piano key. Is it dead, hollow? I want to leap up and tap it with my fingernail. Surely she's got dental insurance. Why doesn't she fix that tooth?

My name is Sophie and I've joined the grief group because... well, because I sort of did a crazy thing. I drove my Honda through our garage door. I was coming home from work one night and- even though my husband has been dead for three months-I honestly thought I would run inside and tell him to turn on the radio because they were playing an old recording of Flip Wilson, whom he just loves. Loved. Ethan had been trying to find a copy of this skit for years, and now here it was on the radio. If I hurried, we could tape it. Then I had the sudden realization that my husband was gone, dead, and the next thing I knew the car was lurching through the door. The wood creaked and crunched as I worked the car into reverse and backed through the splintery hole; then Flip Wilson got to the punch line, "And maybe we have a banana for your monkey!" and the audience roared. My shrink, Dr. Rupert, pointed out later that I could have hurt myself or someone else and insisted I join this group.

The Indian woman sitting next to me lost her twin sister, who was hit and killed by a drunk driver. Her long black braids hang like elegant tassels down the back of her pumpkin-colored sari. She says she and her sister shared a room until they left home, and after that they talked to each other every day on the telephone. Now she dreams that the phone is ringing in the middle of the night. But when she awakens the house is silent; she picks up the phone and no one is there and she can't fall back to sleep and she's exhausted during the day. She hears phones ringing everywhere, in the car, at work, at the store. Now, she shudders and cups her ears with her slender brown fingers. I want to get her number and call her so that when she picks up someone will be on the other end.

Suddenly everyone in the circle is looking at me expectantly, and I wish I'd had a little more time to prepare for the meeting before racing here from work. I can feel my uncooperative curly brown hair puffing in crazy directions, as if it wants to leave the room. On some days it forms silky ringlets, on others Roseanne Roseanna-danna frizz.

"My name is Sophie Stanton and my husband died of cancer three months ago...," I stammer, tucking my fingers into the curls. My voice sounds loud and warbly in the too bright room. I try to talk and hold in my stomach at the same time, because my slacks are unbuttoned under my sweater to accommodate a waistline swollen from overmedicating with frozen waffles; I think I feel the zipper creeping down my former size six belly. That seems like enough for now, anyway. "Thank you," I add, not wanting to seem unfriendly.

"Thank you, Sophie," the social worker says. Her voice is as high and sweet as a Mouseketeer's.

Maybe later I'll tell the group how I dream about Ethan every night. That he's still alive in the eastern standard time zone and if I fly to New York, I can see him for another three hours. That I'm mixing chocolate and strawberry Ensure into a muddy potion that will restore his hemoglobin. When I wake at three or four in the morning, my nightgown is soaked and stuck to my back and the walls pulse around me. But by the time I get to Dr. Rupert's office, I've sunk into a zombie calm. It's sort of like when you bring your car into the shop and it stops making that troublesome noise.

Dr. Rupert says to keep busy. For the past three months I've been rushing from work to various activities: a book club, a pottery class, volunteer outings for the Audubon Society. We rescued a flock of sandpipers on the beach. Something toxic had leaked from a boat into the water, and the birds reared and stumbled and flapped their wings as we scooped them into crates. I rented a Rototiller and turned over the hard, dry earth at the very back of our yard and planted sunflowers and cosmos that shot straight through the September heat toward the sky. Everyone said how well I was doing, how brave I was.

Then I drove my car through the garage door. "Screw the birds!" I yelled at Dr. Rupert in my session that afternoon. "Screw the books, screw the sunflowers!" He scribbled on his little pad, then told me about this group.

There are fifteen of us in the circle. My eyes scan the sets of feet, counting: two, four, six, eight, ten. Two, four, six, eight, ten. Two, four, six, eight, ten. Thirty feet. Fifteen people. Hush Puppies and Reeboks and penny loafers.

The group meets at the hospital where Ethan died. I haven't been back since his death. But I remember everything about this place. How Ethan lay in bed, gray and speckly as a trout. The smells of rubbing alcohol and canned peas and souring flower arrangements. The patients, wrapped like mummies, being wheeled on gurneys through the halls. The monotone pages over the PA, the operator saying things like "Code five hundred" and "Dr. So-and-So to surgery" as calmly as if she were reporting a spill in aisle six.

Great idea! Let's go back to the hospital once a week. You remember the hospital.

Now everyone is looking at me again, and the social worker is saying something.

"Pardon?" "What did your husband do, Sophie?"

I push my glasses up on my nose (a little problem with oversleeping prevents me from wearing my contact lenses these days) and peer out at the circle of forlorn faces. "He was a software engineer." "I see." She adds that to her yellow pad.

How odd to reduce a person to a job title. While he didn't like sweets, he did eat sugared cereals, I want to tell her. His feet were goofy. A couple of those toes looked like peanuts, really. And what a slob. You would not want to ride in his car, because it smelled like sour milk and you'd be ankle-deep in take-out wrappers and dirty coffee mugs. He loved Jerry Lewis movies. One movie made him laugh so hard that beer shot out of his nose. I fight to suppress a giggle as I think of this. Or maybe it's a scream. A dangerous tickle lurks in the back of my throat, and I check to see how close the door is, in case I need to escape.

"And how did you two meet?"

Unfortunately I am clear on the other side of the room from the door, stranded in this circle of feet. A pair of laid-back Birkenstocks scoffs at my uptight career pumps. I clear my throat.

"While I was visiting college friends here for Thanksgiving." I think of how Ethan sat beside me at dinner, moving someone else's plate to another spot while the person was in the kitchen and wedging himself in beside me. Geez, I thought. Strangely overconfident software geek.

"How nice. Did you date from afar at first, then?" "Yes, we had a long-distance relationship for a year, then I moved here and we lived together for a year and then we married." "Very good."

I feel as if I could have said we were embezzlers and the social worker would have thought that was nice.

A few of the other women are widows, too, but they're older than me. One has white hair and glasses with lenses as big as coasters that magnify her eyes, making them look like pale blue stones underwater.

There's a man whose wife was killed in a car accident on Highway 1, and his ten-year-old daughter is having her first sleep-over party this weekend. She told him this morning that she hated him because he didn't know what Mad Libs are, and she wanted Mad Libs at her party, and why did her mother have to die and not him since he's so stupid? The man's voice speeds up and his Styrofoam cup cracks as he squeezes it. A dribble of coffee leaks onto his khakis. He tells us about the dozen girls coming to sleep in his family room this Saturday night and how he wants to surprise his daughter with an ice-cream cake; he's pretty sure that's what she wants, but his wife didn't leave any notes about the party and he's afraid to ask his daughter because he doesn't want to upset her any more.

"I think she likes mint chocolate chip," he says, looking down, his pink double chin folding over the stiff collar of his white work-shirt, which looks impossibly tight.

I want to squeeze his plump hand and tell him it's going to be all right. I know, because I was thirteen when my mother died in a car accident on her way to work, and my father and I were left to fend for ourselves.

That was my first experience with death, and I wished then that I'd gotten a dress rehearsal with a distant, elderly relative. A great-aunt Dolores whose whiskery kisses I dreaded. The only death experience before my mother was my hamster, George, who somehow got confused and ate all of the cedar chips in his cage. I came home from school to find him lying still as a stuffed animal, his water bottle dripping on his head. But there was a new hamster by that weekend who performed all of the old hamster's tricks: running in his wheel and fidgeting with his apple slice and popping his head through a toilet paper roll.

"The death of a loved one isn't really something you ever get over," the group leader explains, leaning forward in her chair. She wears a fluffy white angora sweater with a cowl neck reaching to her chin, so it looks as though her head is resting on a cloud. "Instead, one morning you wake up and it's not the first thing you think of."

While I know she's right, I can't imagine that this morning will ever come to my house.

By now, everyone in the group is sniffling and honking, and a box of Kleenex is making the rounds. As the gold foil box comes my way, I pull out several tissues and hold the wad in my hand like a bouquet. But I'm the only one in the circle who isn't crying. You don't cry at a scary movie, do you? Dr. Rupert thinks the group will help me move from denial to anger to bargaining to depression to acceptance to hope to lingerie to housewares to gift wrap. But it seems the elevator is stuck. For the past three months I've been lodged in the staring-out- the-window-and-burning-toast stage of grief.

Now my cuticles demand my attention. Pick at us, they insist. Yank away. Don't mind the blood. Keep going. At last, a use for Kleenex. As I blot at the blood, the counselor glances my way and says you have to find ways to release your anger.

"Keep a box of garage-sale dishes you don't care about," she suggests. "And break them when you're upset." She says you can lay down a blanket and throw the dishes at the garage, then roll the whole thing up when you're done. She's enthusiastic about how easy this is, as if she's relaying a remarkably simple recipe. It's hard to imagine her stepping on an ant, let alone breaking a service for twelve.

Would it be all right if I threw dishes at my former mother-in-law?

I want to ask the counselor. Marion, Ethan's mother, calls every other day now to insist that she come over and help me pack up Ethan's stuff for Goodwill. I dread the thought of her snoopy paws all over his Frank Zappa CDs and Lakers T-shirts. She'd probably want to chuck his frayed flannel shirts, which I've started sleeping in because they're as soft as moss and smell like Ethan. Marion's house is as neat as a museum. The only trace of the past is one family photo on the baby grand piano. It was taken the day of Ethan's college graduation, and he stands between Marion and Charlie, his father, who died a few months later of a heart attack. Ethan's smiling and the tassel on his graduation cap is airborne, as if it might propel him through the future. Marion looks up at him, bursting with awe.

Marion's always needling me to get ahold of myself. "You have to get back on the horse, dear!" she'll chirp. "Chin up, chin up!" Get-your-act-together euphemisms that say, Look, I'm a widow, too, and now I've lost my only son, but you don't see me driving through my garage door or inhaling pralines and cream out of the carton for break-fast.

I would like to bean Marion with a gravy boat.

Now, even the men are weeping. I'll bet the counselor feels she's making real progress here. I'll bet tears are to a grief counselor what straight teeth are to an orthodontist.

Still, dry eyes for me. Maybe I need the remedial grief group.

Maybe there's a book, The Idiot's Guide to Grief. Or Denial for Dummies.

Maybe this is going to be like ice-skating backward, which I never got the hang of. Or like Girl Scouts, which I got kicked out of for having a poor attitude. I didn't have any badges and wasn't enthusiastic about making my coffee-can camp stove and wouldn't wear that Patty Hearst beret while selling cookies. (It was hot and made your ears itch!) The troop leader, Mrs. Swensen, called my mother to say that I should find an after-school activity I was more enthusiastic about. She didn't know that I had been working on the cooking badge. I'd written a little report on paprika-although it was mostly copied out of the encyclopedia-and learned to make pie crust, rolling out the dough until it was as thin and transparent as baby's skin. "Too thin, sweetie," my mom commented, pointing at the huge disk of dough glued to the countertop. Anyway, I was relieved to be free of Girl Scouts, preferring to lie on my bed and listen to Casey Kasem's countdown, chewing banana Now and Laters and reviewing the repeats in the daisy wallpaper pattern to soothe my nerves. Flower, flower, stem. Flower, flower, stem.

Now, it doesn't look as if I'm ever going to get the grief badge. I look out the window at the brittle, leafless trees, their branches like bones in the sky.

And that's all the time we have today.

"The warmth of the body causes the patch to adhere," I explain to the Herald health care reporter who's interviewing me by telephone for an article he's writing. As public relations manager at Gorgatech, I'm supposed to improve the image of a scrotal patch product that's prescribed to men whose testosterone production is off-kilter on account of illness. A scrotal patch! Why can't I work on the headache product? The problem is, the patch doesn't always stick. Just imagine some poor guy in a sales meeting looking down and suddenly discovering a thing like a big square Band-Aid clinging to his sock.

"For some patients the patch may not adhere completely," I admit. "In which case it should be warmed gently with a hair dryer before application."

The reporter snorts. He points out that another company markets a gel. The disdain in his voice suggests he'd rather talk to a used-car salesman than a PR flack.

"True, but the patch provides a steadier dose," I explain. I look over the padded beige walls of my cubicle at the pockmarked ceiling tiles. Someone's piping sleepy gas into the office. I want to curl up on the floor with my head on my purse and just sleep.

My boss, Lara, a size two Armani jackhammer, says I have to get two positive media stories on the patch-one local and one national-by the end of November. That leaves about five weeks for me to redeem myself. Lara's quick to point out that there haven't been any media stories on our company or products since she hired me. She says that if I don't nail the two stories, she'll slam my hands in her desk drawer, severing several fingers, and I'll never be able to type again. Then she'll fire me, and the mortgage company will auction off my house. She didn't say this with words. She said it with her eyes, with the quick cock of her head, her lips pursing into a little red knot. If this guy writes a positive story, I'll be halfway through my quota.

"Most patients aren't bothered by the minor inconvenience of using the dryer," I tell the reporter, reading from my tip sheet, "because of the benefits of the product." I imagine my mailbox at home stuffed with property tax statements and soaring electric bills. The problem is, I like to keep lots of lights on at night so it seems as though people are home. "On low heat, though," I tell him. "Never high."

The clacking of the reporter's keyboard and his intermittent chuckles make me nervous. He wants to know if I really think guys travel with blow dryers, if they own blow dryers. "We provide complimentary dryers upon request." At least I think we do. I probably shouldn't stray from the tip sheet.

The reporter says he has to go so he can meet his deadline. As I listen to a long silence and then the dial tone, I think of how my other English major friends have more noble jobs: one's a travel writer in Paris, another teaches creative writing to women prisoners. Finally I hang up the phone and get back to work on the press release I'm composing about the patch. It's nearly lunchtime and I've made little progress. There's a pea-size hole in my panty hose just under the hem of my skirt, and I've taped it to my leg so it doesn't head south.

I think of the white-haired lady in the grief group whose husband drove her everywhere. I picture them in a Chevy Impala driving forty-five on the freeway, two cottony heads peering over the dashboard. I wonder if it is worse to be widowed later in life, when you and your spouse are as attached as roots to a tree. The cursor on my computer screen blinks: mort-gage, mort-gage, mort-gage.

When I first moved to Silicon Valley to be with Ethan, I found a job I liked editing university publications. I had my own office, with ivy growing along the windows, and went home every night by six. But at parties, other women in their thirties compared BMW models and how many direct-reports they had at work, and I decided I needed a higher-paying job with stock options. What kind of loser worked at a place without stock options?

I got this job during Ethan's remission, after he'd finished his radiation therapy and it seemed that he would be all right. This gave me a brief surge of confidence, during which I drove down the freeway at eighty miles an hour with the moon roof open, the wind in my hair, old songs like "I Will Survive" and "A Girl in Trouble (Is a Temporary Thing)" blasting on the stereo. Then the cancer came back, this time as a tumor in Ethan's chest. It was the home wrecker that stole my husband. I almost wished it had been another woman-a slutty thing in a miniskirt whose tires I could have slashed.

I hardly took any time off after Ethan died-just the three allowed bereavement days and the two sick days I'd accrued. Coworkers stopped by my cube and asked, "How are you doing?" I wanted to tell them not to worry; my husband was only out of town, maybe at a trade show. He'd be back.

Ethan's presence in our house was palpable, his loafers and sneakers lined up in the closet and his Smithsonian and Wired magazines still arriving every month. But all too soon floury dust coated Ethan's shoes, and his toothbrush grew dry and hard in the cup on the sink, and his pile of unread magazines toppled over.

People stopped saying, "How are you doing?" and Lara started assigning the black diamond projects again. This damn patch.

Lara whistles into my cube now. "Don't bother with a press release," she says, looking over my shoulder at my keyboard, hands on little StairMaster hips, blond hair pulled into a high, tight ponytail.

"Just get a story. Call The Wall Street Journal." I cower at the keyboard, thinking of the leak underneath my house. A few weeks ago a plumber in coveralls crawled through a trapdoor in the front hall closet and reported that it would cost $2,000 to repair the leak and install a sump pump. Money I don't have right now. "You folks need a pump," he said. "It's just me," I told him.

If you reach behind the coats and lift the slab of wood, you can see the black puddle, which smells like iron. My car would like a piece of my paycheck now, too. It's been making a grinding noise and pulling to the right, as though it would rather drive through the trees.

"Okay? Okay?" says Lara. Although she's only five-three, she somehow manages to tower over people.

"Okay." I flip slowly through the Rolodex on my desk. Later, when I can breathe, I'll tell her about the Herald story. She huffs a sigh of exasperation and leaves me in a pit of Willy Loman cold-call despair.

On my way home from work that night, I get in an accident: I'm broadsided by the holidays. It happens when I stroll into Safeway and see the rows of tables by the door stacked high with Halloween candy: Milky Way, Kit Kat, Butterfinger. Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas. Stop, turn, run! I try to shove my cart toward produce, but it won't go. One stubborn wheel tugs like an undertow toward the candy. I kick the cart and focus on my shopping list: eggs, milk, ice cream.

I make it safely to produce, but there the pumpkins lurk. Look! they shout. The holidays are coming! I spot the bunches of brown corn you can hang on your door and the tiny gourds-the bumpy acne ones and the clown-striped green-and-yellow ones. I lean into the cart for support. How can a place called Safeway seem so dangerous?

Last Halloween Ethan and I took Simone, the daughter of my college girlfriend, Ruth, trick-or-treating. Ethan dressed up as Yellow Man, his own made-up superhero. He wore a yellow T-shirt, yellow rubber gloves, and a yellow rain poncho for a cape. He made Simone laugh so hard, she choked on a Gummi Bear.

I remember the yellow yarn dust mop bobby-pinned to his head. I remember his hair-the sweet, almost eggy smell of Flex shampoo. Beautiful hair! Thick, straight, shiny, and brown. The hair I always dreamed of having instead of my wiry curls. Sometimes a Dennis the Menace piece stuck straight up on top of Ethan's head, which is probably why he got carded. He was thrown together in a boyish way-baseball caps and too-big sweatshirts, Converse sneakers with no socks, dirt on his knees from crawling around in the backyard looking for his Frisbee. Why did I ever sign that paper to have him cremated? That's what he wanted. To have his ashes spread at Half Moon Bay, where we went for our honeymoon.

It made sense at the time. But now there isn't even a grave to visit. How can I be a widow when there's no grave? "Miss?" A clerk clutching a bunch of basil stands beside me. "Are you okay?"

"Yes." He said miss and not ma'am. Sweet. There are streaks of cranberry red spots on his cheeks, and his nose shines. I try to think of something to say, a vegetable to inquire after. Instead I blurt: "My husband died." Maybe this is the first time I've said this. I'm not sure. I think it is. Suddenly I'm crying, that little-kid gulping kind of crying, where you can't catch your breath. The morning after Ethan died, I resented the mourners collecting in my living room. How could they fall into the role and accept Ethan's death so readily? While they wept and carried on, I cleaned the house.

Scrubbed the shower grout with a toothbrush and Clorox. Now I'm one of the howling mourners. But they've wrapped it up already, moved on.

The clerk touches my elbow and leads me through the big swinging double doors by the coolers with the chicken. He says, "Careful," as we walk up a narrow flight of stairs. There's a leaf of lettuce on one stair. We shuffle into a break room and he seats me at a long brown Formica table. He's probably only in high school or junior college. He sets a cup of tea and a box of tissues on the table. "You take your time," he says.

I'm suddenly embarrassed and want something to do to look busy. I grab one of the tissues and begin cleaning my glasses. Okay, so Ethan isn't coming back. The sympathy cards reverted to phone bills months ago. Even telemarketers have stopped asking for him.

Oh! The tissues have lotion for sore noses, and the lenses of my glasses now look as though they've been dunked in salad dressing. The room is blurry. The boy is gone. The holidays are coming. Can I stay in this break room until after New Year's?

At home the phone rings as I'm peeling off my coat. I let the machine pick up.

"Hello? Sophie?...Dear? Are you there?" It's my mother-in-law, Marion, who's not really comfortable around answering machines, VCRs, and other newfangled devices. She clears her throat.

"Well, I'm calling for two reasons. One, there's a sale at Talbot's, and I'd like to take you to buy a few new things. I thought that might cheer you up." Marion always seems to wish I'd shop at Talbot's, that I'd dress more like a country club wife than a frumpy neo-hippie-frayed jeans and clogs and my husband's too big sweaters. Once in a while Marion wears jeans, "dungarees," she calls them, but she irons stiff creases in the legs that stand up like little tents. "The other thing is, dear, I'd like to make a date to come over this Sunday and pack up Ethan's things for the Goodwill. Remember, we talked about that? I really feel it's time, and it'll be a breeze if we work on it together...."

A breeze?

A tornado.

There are no groceries to unload, since I abandoned my cart at Safeway. I head straight for the bedroom and crawl under our king-size quilt, choosing to sleep in my clothes to ward off the icy corners of the bed.

I dream that I run into Ethan in downtown San Jose by the convention center when I'm on my way to the library. His hair glistens like a mink coat and I want to touch it. He's with a policeman. They explain that Ethan's been in a car accident and the officer is trying to help him find his way home. I look down and see the edge of Ethan's hospital gown hanging out from under his parka, the little blue snowflakes on the fabric fluttering in the breeze. I want to tell him that he wasn't in a car accident. He had cancer and now he's dead. But I'm afraid I'll hurt his feelings, like telling someone they could lose a few pounds or their clothes don't match.

When I make it to work the next morning, the Herald is spread across my desk. I'm supposed to read the paper every morning before getting to work, so I'll know if the company has been in the news. I'm also supposed to scan the national press and be up on current health care issues so I can pitch stories relating to our products.

Spins, pitches, angles. I always mean to do this. But mustering the courage to leave the house every morning leaves me too enervated to lift the pages of Time or Newsweek. I read the health care reporter's lead for the patch story. Gentlemen, start your hair dryers.

I can't read the next line, because there's a Post-it note stuck over it with a note from Lara: See me.

The bum fluorescent bulb over my cube ticks and buzzes like a cicada.

I head straight for Lara's office without taking off my coat. Lara and I are opposites, and in our case opposites deflect. She's only two years older than me-thirty-eight-but she's already a vice president.

She's as polished as a lady news anchor, and her whole being seems dry-cleaned. She meets her personal trainer at the gym every morning at five, arrives at work by seven-thirty, eats lunch at her desk-peeling the bread off her turkey sandwich to avoid the evils of carbohydrates-and leaves at seven-thirty in the evening. I get up at five in the morning, too, but only to pee, my sole workout being a shuffle to the john. The next time I wake it's ten minutes before I'm supposed to be at work, never mind the forty-minute, second-gear commute and the fact that my hair is in one long snarl like the Cowardly Lion's in The Wizard of Oz.

As I stand in the doorway to Lara's office, she's on the phone. "Un-huh, un-huh, un-huh," she says impatiently, punching her PalmPilot, sipping coffee out of a giant mug, and checking her e-mail. She motions me in. I hover at the threshold. Simon says: Go into your boss's office! I take a big step in. She yanks off her headset and tosses it on her desk. Her expression is in the fully upright and locked position.

For the first time, I almost wish I'd get fired. I would probably be eligible for some kind of severance or unemployment. I could get roommates to help pay the mortgage. We could do the Jumble together and cook pot luck suppers. I can live off a couple weeks' salary for a little while. I actually like chicken pot pies....

"Sit," says Lara. I sit. Good dog? Bad dog.

"We'll get a correction printed." She smiles, containing her irritation. Her teeth are so white, they're almost transparent; I think she used her bleaching trays a few too many nights.

"Right," I tell her, as though I've planned this all along. I realize I'm still wearing my coat. "Did you take this reporter to lunch?"

Lara has a real thing for taking reporters to lunch. She thinks you can control the media with smoked turkey and fusilli salad. I shake my head. Bottom line: The patch doesn't stick. "I'd like to be able to tell Ed by noon that a correction will be printed tomorrow morning."

Ed's the CEO. Turn down your teeth, I want to tell Lara. I can't hear you. Instead, I nod. "I'll get on it." First, get me out of this oxygen-depleted room.

Of course, this doesn't count as one of my two media placements due by the end of November, since it didn't even mention the downsides of the competing product. But when I get back to my cubicle, I realize there aren't any errors in the story. It's all about tone. It's a tone piece. Tone, voice. This reporter has found his voice! It is the voice of an asshole.

The phone rings. I pick it up. "Hello?" a man says.

I know he'll ask a question I can't answer. I'm supposed to be able to remember scads of facts for this job: each product name, its generic name, its indication, whether it has a trademark or service mark, how long it's been on the market, whether it's part of a joint marketing and distribution agreement. Then there are the common side effects, adverse reactions. But since Ethan died I can barely retain a seven-digit phone number. I slide one finger over the button on the phone, hanging up. The man will think we got disconnected.

When the phone rings again, I let it drop into voice mail.

I open a new file on my computer and start typing what to say to the Herald reporter about the patch story. This is a trick I employ when I have to make a nerve-racking media call: Type my story pitch or sound bite in all caps, then follow the script.

MUST PATCH THIS ALL UP. HA, HA, HA!

I remember when I first joined the company how I felt I was finally making it in Silicon Valley. I stood in the coffee line chatting with the women from marketing, all of us wearing cute but sensible chunky black pumps, my day planner bulging, my checkbook balance growing, my self-esteem swelling. But now I feel like an impostor in a cubicle-like the artificial crabmeat of public relations managers. Then there's the fact that I have to say "scrotum" to people all the time. Is this really the color of my parachute? If Ethan were alive, I'd call him and we'd meet for lunch. We often did this when one of us was having trouble at work. We had a knack for solving each other's job quandaries, maybe because our ignorance of each other's fields made us objective. Sometimes he'd pick me up after work and I'd be so flustered by this new job, I was ready to quit and start a yard service. By the time we got home, though, Ethan had me laughing and contemplating a solution.

Of course, I can't call my husband. (But why not! What good is all this technology if you can't call a deceased loved one? Who cares if you can buy movie tickets and bid for antiques on-line if you can't dial up your dead husband?)

The cursor on my computer screen pulses impatiently, and the red voice mail light on my phone flashes. My stomach growls and my head throbs. But I can't call my husband. Because, here's the thing: I am a widow.

Good Grief

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-10: 0446694843

- ISBN-13: 9780446694841