Excerpt

Excerpt

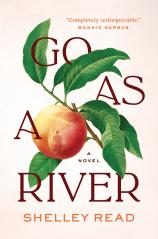

Go as a River

1948

He wasn’t much to look at.

Not at first, anyway.

“Pardon,” the young man said, a grimy thumb and forefinger tugging at the brim of his tattered red ball cap. “This the way to the flop?”

As simple as that. This ordinary question from a filthy stranger walking up Main Street just as I arrived at the intersection with North Laura.

His overalls and hands were blackened with coal, which I assumed was axle grease or layers of dirt from the fields, though it was too dark for either. His cheeks were smudged. Tan skin shone through trickled sweat. Straight black hair jutted from beneath his cap.

The autumn day had begun as ordinary as the porridge and fried eggs I had served the men for breakfast. I noticed nothing uncommon as I went on to tend the house and the docile animals in their pens, picked two baskets of late-season peaches in the cool morning air, and made my daily deliveries pulling the rickety wagon behind my bicycle, then returned home to cook lunch. But I’ve come to understand how the exceptional lurks beneath the ordinary, like the deep and mysterious world beneath the surface of the sea.

“The way to everything,” I replied.

I was not trying to be witty or catch his notice, but the angle of his pause and slight twist of smile showed that my response amused him. He made my insides leap, looking at me that way.

“Real small town, I mean.” I tried to set things straight, to clarify that I was not the type of girl that boys noticed or paused to smirk at on a street corner.

The stranger’s eyes were as dark and shiny as a raven’s wing. And kind—that is what I remember most about those eyes from that first glimpse until the final gaze—a gentleness that seemed to fountain from his center and spill out like an overflowing well. He studied me a moment, still grinning, then pulled again at his cap brim and continued walking toward Dunlap’s boarding house near the end of Main.

It was true that this one crumbling sidewalk led to everything. Along with Dunlap’s, we had the Iola Hotel for fancy folks and the tavern tacked on the back for drinking folks; Jernigan’s Standard station, hardware, and post; the café that always smelled of coffee and bacon; and Chapman’s Big Little Store, with groceries and a deli counter and too much gossip. At the west end of it all stood the tall flagpole between the schoolhouse I once attended and the white clapboard church where our family used to sit, polished and proper, every Sunday when Mother was alive. Beyond that, Main Street dove abruptly into the hillside like a period after a short sentence.

I was heading in the same direction as the stranger—to drag my brother out of the poker cabin behind Jernigan’s—but I wasn’t about to walk right on this boy’s heels. I paused there at the corner and shielded my eyes from the afternoon sun to study him as he continued on. He strolled slowly, casually, like his only destination was his next step, his arms swinging at his sides, his head seemingly a tad behind the pace. His dingy white T-shirt stretched tightly beneath the straps of his overalls. He was slim, with the muscular shoulders of a workhand.

As if he felt my gaze, he suddenly turned and flashed a smile, dazzling against his soiled face. I gasped at being caught eyeing him. A rush of heat tickled up my neck. He tugged his cap as he had before, turned, and strolled on. Though I couldn’t see his face, I was pretty sure he was still grinning.

It was a fateful moment, I know in retrospect. For I could have turned and headed back down North Laura, toward home and fixing supper, could have let Seth stumble to the farm on his own accord, stagger in the door right in front of Daddy and Uncle Og with his own hell to pay. I could have at least crossed over to the other side of Main, put the occasional car and a row of yellowing cottonwood trees between our two sidewalks. But I didn’t, and this made all the difference in the world.

Instead, I took one slow step forward and then another, intuitively feeling the significance in each choice to lift, extend, then lower a foot.

No one had ever spoken to me about matters of attraction. I was too young when my mother died to have learned those secrets from her, and I can’t imagine she would have shared them with me anyway. She had been a quiet, proper woman, extremely obedient to God and expectation. From what I remember, she loved my brother and me, but her affection surfaced only within strict parameters, governing us with a grave fear of how we’d all perform on Judgment Day. I had occasionally glimpsed her carefully concealed passion unleash on our backsides with the black rubber flyswatter, or in the subtle stains of quickly swept tears when she stood after prayer, but I never saw her kiss my father or even once take him in her arms. Though my parents ran the family and the farm as efficient and dependable partners, I didn’t witness between them the presence of love particular to a man and a woman. For me, this mysterious territory had no map.

Except for this: I was looking out the parlor window on that gloomy autumn twilight just after I turned twelve years old when Sheriff Lyle pulled up the wet gravel drive in his long black-and-white automobile and hesitantly approached my father in the yard. Through the steam of my breath on the glass I saw Daddy slowly collapse to his knees right there in the rain-fresh mud. I had been watching for my mother, my cousin Calamus, and my Aunt Vivian to return, hours late from making their peach delivery across the pass to Canyon City. My father had been watching too, so antsy about their absence he spent the whole evening raking the soggy leaves he’d normally allow to compost on the grass over winter. When Daddy buckled under the weight of Lyle’s words, my young heart comprehended two immense truths: my missing family members would not be coming home, and my father loved my mother. They had never demonstrated or spoken to me of romance, but I realized then that in fact they had known it, in their own quiet way. I learned from their subtle relations—and in the dry, matter-of-fact eyes with which my father later walked into the house and somberly shared the news of my mother’s death with Seth and me—that love is a private matter, to be nurtured, and even mourned, between two beings alone. It belongs to them and no one else, like a secret treasure, like a private poem.

Beyond that, I knew nothing, especially not of love’s beginnings, of that inexplicable draw to another, why some boys could pass you by without notice but the next has a pull on you as undeniable as gravity, and from that moment forward, longing is all you know.

There was merely a half block between this boy and me as we walked the same narrow sidewalk at the same moment in this same little nowhere Colorado town. I trailed him, thinking that from wherever he had come, from whatever place and experience, he and I had lived our seventeen years—perhaps a bit longer for him, perhaps a bit less—wholly unaware of the other’s existence on this earth. Now, at this moment, for some reason our lives were intersecting as sure as North Laura and Main.

Go as a River

- Genres: Fiction

- hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher: Spiegel & Grau

- ISBN-10: 1954118236

- ISBN-13: 9781954118232