Excerpt

Excerpt

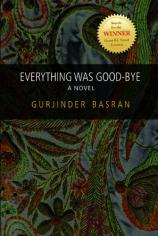

Everything Was Good-bye

The smell of chai—fennel, cloves and cinnamon—tucked me into my blanket like a seed in a cardamom pod. I steeped myself into the warmth of waking, listening to the sounds of Sunday morning. My mother was in the kitchen scrubbing the sink, her steel kara clinking against the basin—keeping time with the shabad on the radio. When I was fifteen, I’d told her I didn’t want to wear my kara anymore; I didn’t like the idea of being handcuffed to God. My mother, to my surprise, hadn’t argued with me but simply said that the kara was a symbol of the restraint I would learn to show whether I wore the bangle or not. “Is Meena not awake?” my mother asked, her voice cracking through intermittent radio static.

“Get up, Meninder. It’s eleven o’ clock.” My sister Tej was the only one who used my real name; she knew how much I hated it.

I heard her footsteps in the hallway and pulled the blanket over my head.

“Just five minutes.”

“No, not five minutes. Mom wants you up now. I don’t know why you think you get to sleep in while I get stuck with all the chores. You’re such a brat.” Tej yanked the blanket off and looked at me with disgust. I was sleeping in a tank top and panties instead of the old-lady nightgowns that Masi had sewn for us from scraps salvaged from the textile mill.

“Fuck off, Tejinder.” I shut my eyes against the light and pulled the blanket over my shoulders.

“Why can’t you wear proper pajamas like everyone else, or at the very least a bra?”

“You’re just jealous.”

Tej crossed her arms over her flat chest and stared me down, silent and saintly, until I felt the familiar beginnings of guilt harden in my stomach and take root in my toes.

She reached across the bed, drew the blinds and slid the window open, filling my room with the sounds of barking dogs, sprinkler jets and crows. When I turned my back on Tej, she shook my shoulder, stood over me, arms crossed, mouth zipped. She seemed unhinged.

“What?”

Tej stormed out of the room, muttering complaints to my mother, who yelled louder for me to wake up.

I kicked the covers off, stretching and collapsing my limbs before relaxing into my waking self. I lingered in my own touch, daring a quiet and quick exploration, cupping my breasts, running fingertips over flesh and folds. I wasn’t sure exactly when my body had changed but it seemed to have done so in secret. I’d woken up one day the previous summer with Bollywood breasts, curvy hips and long legs. My dreams realized were just the continuation of my mother’s nightmare. Like my sisters, I was no longer allowed to play sports or wear shorts. Our sex was meant to be hidden, even from one another. We dressed modestly, hiding our flesh, living somewhere deep inside our skins—chaste and quiet.

My mother was seated at the kitchen table, the Sunday paper splayed in front of her, sliced and dissected to the weekly flyer section. She flipped through ads for laundry detergent and dog food while talking on the phone to my sister Serena, scrunching her face, pushing her oversized glasses up ever so slightly to magnify portions of the page. I sat next to her, drinking a cup of stale tea, wondering why she bothered with reading glasses when she could not read.

“Eighty-nine cents,” I told her impatiently. “Limit six.”

She stared curiously at the picture of canned beans before licking the tip of her middle finger and turning the page.

“Achcha, achcha… it’s expensive yes, but if you buy them in the case…When you were kids we used cloth diapers; it was so much work… Well you have to be disciplined, put him on the potty every few hours, he will get used to it… None of my children wore a diaper at his age… Tonight, the party… Who is it?… achcha achcha, his cousin’s wedding.”

Her voice skipped and jumped, picking up threads from the previous day–a patchwork of words. She flipped to the next flyer, told Serena that Similac Infant Formula was on sale at London Drugs, then sat squinting at the fine print.

“One case per household,” I read for her.

My mother nodded as though she expected as much; she probably did. She knew which stores had the freshest vegetables, which had the cheapest; she knew the weekly sale cycle of all the local shops and had a well-stocked wallet of coupons grouped by date and commodity. She could figure out the price of toilet paper by the square, never fooled by the ever-changing sheet count per roll. She took her flyers and coupons to stores, looking for price matches and bulk buys. She knew the clerks and cashiers by face and at times attempted some small talk about the weather, but none of them ever returned the kindness. This only motivated her to count her change more closely, enumerating each penny on a rung of her finger the same way she counted minutes, hours and days. Once a cashier accused my mother of stealing a chocolate bar. The pimply faced security guard took her to the back office and went through her purse and pockets. After finding nothing, he sent her on her way with a warning. She came home upset and confused, much the same way I did when I was teased at school. When she told me what had happened I drove her back to the store and demanded to speak to the manager. He was apologetic about it and every time he’d seen her since, he was sure to ask her how she was doing, whether she needed anything. He even helped take her groceries to the car. My mother told everyone about it. “You should have seen how Meena talked to them. They even gave us a store gift certificate.”

“Get dressed,” my mother said, glancing at my jeans.

“I am dressed.’’

“Don’t argue. Not now. We are expecting guests.”

Phone still wedged between her ear and shoulder, she stood, moving like a pecking bird, as though in a hurry yet somehow unsure of her destination.

She put the dishes in the sink and stared out the window, her marionette frame bent in at the shoulders, her head lowered. The window looked out over the neighbors’ manicured lawn, the perfectly pruned boxwood hedge and the grapes that wound along the fence. As usual on a Sunday, the neighbors were out on the lawn playing bocce. Their loud Italian voices and exuberance for life kept my mother curious and she watched them through the broken slit in the blind, as though trying to decipher their happiness. Sometimes they saw her standing at the window and waved “hello” or beckoned “come over.” Today, as always, she turned away seeming both embarrassed and shy—feelings that for her and me were interchangeable.

“Why are you still standing there?” she said, turning on me. “I told you to change your clothes.”

In my room I pulled out a plain salwar kameez from the bottom dresser drawer. The satin made me sweat and the smell lingered into the next wear, reminding me that I hated wearing Indian suits almost as much as I hated this ritual of belated mourning. Even though my father had been dead for sixteen years there were still enough relatives to fill every Sunday with pity. It was always the same. We would get up, clean the house, do the laundry, mourn the past and go to sleep. We existed between past dreams and present realities, never able to do anything but wait. For what, I didn’t know.

When I was five, I’d thought we were waiting for my father to return. I had no memory of him but attempted to stitch his life together from the remnants that were everywhere. The house was full of black and white photographs of him from when we lived in England. Pictures of him standing next to the guards at Buckingham Palace and of the family in front of a tiny brick row house on Warwick Road still graced the mantel. Even my mother’s closet was full of him. His starched cotton dress shirts hung neatly alongside sports jackets that smelled like yesterday’s rain. His brown-and-black leather shoes were lined up beneath the shirts and jackets, next to a locked suitcase that I pulled out to stand on in order to reach the top of the closet.

Buried on the top shelf, I found an attaché case full of documents, which I could not yet read, and behind it a photo album and shoe polish kit. Resisting the urge to shine my father’s shoes, I sat cross-legged beneath the empty embrace of hollow-armed suit jackets and opened the album. The yellowing photos made every face look familiar. They were the usual assortment of pictures—birthdays, weddings, picnics—except for four photos on the last page that were turned over.

I sat for a moment, wondering what was on the other side, before pulling back the plastic protector and peeling one of the photos off the sticky surface. It was a picture of my father in a pink satin-lined coffin. A long garland of spring flowers like the ones I’d seen worn by newlyweds was draped around his neck. His eyes were closed and weighted, his shoulders rigid, chest tight as though he were holding his breath.

My heart skipped and fell. The descending beats echoed in my chest, palpitated in my breath. I put the photo back in the album and the album back on the top shelf, preserving my father’s death just as my mother had so carefully preserved the details of his life. Just as my father’s mother—my dadi—had when she’d come to Canada to mourn her son five years after his death.

“How we remember,” my dadi told me and my sisters, “this is how we exist.”

“The past is the only thing that matters,” she said, shaking her head like a slow pendulum between bitter glances at our braids. “It is the only thing we know.”

“We cannot make something out of nothing. That is for God to do.”

This is what we were told. This is who we were.

After dressing, I returned to the kitchen to finish my breakfast. I was always a slow eater. My mother had to force-feed me as a child, every spoonful of curry followed by a gulp of water to wash it down; I hated the bitter subzi, soft and chunky mounds of potatoes and cauliflower. “Shit”—that’s what the white kids at school had said my leftover lunches looked like. “Meena eats shit.”

Tej shuffled by me, pushing the vacuum with one hand while balancing a laundry basket of wet clothes on her hip like a baby. She leaned against the table and pushed the basket towards me. “Your turn to put these on the line to dry. And you have to vacuum. Mom and I are going to the Indian store to get groceries.”

She held up a list of chores that I would need to complete by the time they returned. I took the list from her, crumpling it in my free hand as I opened the porch door to hang the laundry out. I closed the door on her curse words.

Our porch backed onto a fenced-in grid of suburban yards dotted with broken-down garden sheds and vegetable plots that were a haven for squirrels and other rodents. No matter how quickly we picked up and composted the rotten apples and spoiled cherries, the critters would come up from the nearby bog, skulking along the top of our rickety fence in search of a meal. Once, one of the kids at school saw me chasing a raccoon off our garbage bins with a broom handle and looked disgusted, as though having raccoons in our neighborhood were somehow my fault. We lived in one of the older grids in North Delta, a suburb just outside of Vancouver, where the large evergreens and pines were dying a slow death, mostly by crowding and years of various untreated seasonal diseases that caused the bark to peel away in long, ragged strips.

The houses on our street had been bought and sold several times and were victim to shoddy renovations, like the slanted sunroom addition next door. New neighborhoods were devoid of such things; the ones built on flattened forests above the ravine had courts, boulevards and crescents that wound around one another to panoramic views of Boundary Bay. Each new cedar house there looked onto both a dogwood tree planted in the sidewalk meridian and a carefully manicured postage stamp-sized front yard filled with some variation of tulips, daffodils and rhododendrons. Behind the cedar fences draped in clematis were the popular girls who spent their weekends sunbathing, sometimes topless (so the boys at school said), listening to Casey Kasem’s American Top 40. On a clear day I could hear them splashing in their pools and singing along with Madonna. None of them had to chase away raccoons or spend their Sundays hanging their knickers on a clothesline for the world to see.

I snapped the mismatched sheets in the air and pegged them onto the line. In the distance a squall of cloud was rising and I wondered how long it would be before the rain set in. The clouds were jagged at the ends, torn sheets of grey sky, not the kind of drifting childhood pictures that my sister Harj and I had imbued with meaning. “A boat! A car! A plane!” I’d yell. “How unoriginal,” she’d laugh. Of a cirrus cloud, I once said, “Whipped air and angel hair.” Harj was lying in the grass at the time, picking at a scab on her elbow. “Only white people can be angels,” she said, without looking up.

Halfway through my wash-load hanging, Liam appeared, walking towards the house, his long afternoon shadow turning corners before he did. As always, he was wearing his headphones, and I wondered if he was listening to the mixed tape I’d made him for his birthday.

I’d met him at the beginning of Grade 12. He’d transferred from Holy Trinity and at first didn’t go to class, preferring to wander the hallways and occasionally kick a locker door as he passed. He was rumored to have been expelled from the Catholic school, but no one knew why. Some kids suspected he’d been kicked out for drug use and others had heard that he’d been in one too many fights, but what everyone agreed on was that he was best left a loner. Whenever he walked by, people veered out of his way, and in the crowded hallways he stood apart from the others in what seemed like contented arrogance.

Moments before our first meeting, I was rushing across the field, my face tucked into an armload of books to avoid the sun’s glare. As I approached the school’s main entrance, I saw him scaling the face of the building as if he were Spiderman. Just as I was about to walk by, he jumped down, falling at my feet. Startled, I dropped my books. The bell rang. I was late. I knelt down and began collecting the books, occasionally grasping at my papers as they fl uttered in the breeze, threatening to take flight. Liam handed me a stack of papers and a few books.

“History, don’t want to lose that one.”

“Actually, I would. But thanks.” I looked up to take them from him. The sun should have been in my eyes, but he had eclipsed everything.

Later that same day, I’d found myself sitting in front of him in history. The teacher hadn’t arrived and the class was on the verge of the usual anarchy. Liam slumped over his desk, ducking under a paper airplane as he tapped my back with his pen. “Meninder, right?”

“Meena,” I corrected, wondering how he knew my full name.

He squinted and nodded his head as if to say “All right, yeah.” He had a face that was older than his age, a square jaw line and blue eyes that changed color depending on the light.

“You live in the beige house, the one with the fucked-up trees?”

I hesitated not wanting to encourage a conversation. “Yeah, why?”

He leaned back into his chair until the front legs lifted off the ground. “So, you want to get out of here?”

“And go where?”

“Does it matter?”

When I said it did, he smirked as if I had missed something obvious, and left the classroom, leaving me alone and surrounded by kids who acted like I didn’t exist.

After class, he was waiting outside and asked if he could walk home with me. After working up the courage, I asked him where he ended up going and he told me, “You know, just around.”

He always said “you know” as though I did know. Somehow it made me think I did.

I pegged the last of the wash on the line and cranked it out towards the remaining patch of sun. Liam stood beneath the porch and looked up at me.

“What’s up?” I asked.

“Nothing. I was going downtown, thought you might want to come.”

“I can’t.” I looked to see if my mother had seen us talking. “We’re expecting company and I have some stuff to do around here.”

“Like laundry,” he said, picking up a few of the pegs that I’d dropped. When he started up the steps to hand them to me, I rushed down the stairs, carrying the basket in front of me so he wouldn’t see me in my Indian clothes, though I suspected he would’ve seen beyond them. He never seemed to notice when my hair smelled like curry or when I wore the same clothes two days in a row.

I took the pegs from him.

He was smiling or smirking at me. I couldn’t tell which; his slight underbite made everything seem like a flirtation or dare.

I stood there in Liam’s silence. He was often like this; he didn’t feel the need to speak, to fill in the blanks, to use up air. Talking with him was always a relief.

“Maybe we could do something tomorrow?” I suggested.

“That’d be cool,” he said.

“Meena!” my mother yelled from the window, in a tone that matched the glare she shot at Liam.

“Look, I have to go. See you tomorrow.”

I rushed back up the stairs and took the empty basket inside, walking by Tej and my mother, who were on their way out.

“Gora? A white boy?” my mother snapped.

“He said hi. What was I supposed to do, not talk to him?” I pushed the vacuum into the living room and flicked it on, drowning out any hope my mother had of lecturing me about talking to white boys.

White was the color of death and mourning; it was the only color my mother wore apart from grey. In the kitchen, while ironing her chunni, she reminded us how to behave when the guests arrived. Tej listened and replied dutifully in her pitiful Punjabi. Although we’d attended Punjabi summer school when we were kids, her accent was still terrible—she couldn’t say the hard “it’s” the way I could but I couldn’t be bothered to make the effort, and answered my mother’s Punjabi in English. I wondered how much was lost in this routine, which forced us to follow along a word at a time, or a word behind, interpreting what was said even when, for some expressions, there was no translation. My mother would often get frustrated and remind me that when I started preschool the only English word I knew was good-bye. As we walked home from school that first day, I waved good-bye to the bus stop, the lamppost, the trees… My mother yanked my hand, pulling me along, tired of my valediction. “Everything was goodbye,” she told my sisters later.

Steam rose to her face as she pressed the wrinkles from her chunni, the heat forcing her to look up. “Tie up your hair,” and then with one motion of her hand dismissed me to the basement washroom. She didn’t want us to use the upstairs washroom; she’d emptied the garbage and removed the diaper box-sized packs of Kotex that proved this was a house full of women. I’d been mortified when she stuffed our shopping cart full of those discounted maxi-pads at Zellers. I wanted to use tampons like the girls at school but my mother regarded the insertion of such an object as impure. I bought a box anyway and stashed it under my bed, along with the birth control pills Serena bought for me. I was only eleven when I got my fi rst period and since my mother hadn’t let me watch the sex ed. films at school, I was sure I was bleeding to death—I thought kissing made you pregnant. After a day of enduring excruciating cramps and hiding my soiled panties in the corner of my bedroom, I confided to Serena that I was dying. When Serena told my mother that I’d started to menstruate, my mother didn’t speak to me for a week. My becoming a woman so early was a shameful reminder of our sex, of the burdens she bore.

My cramps were awful and I spent the first two days of each month at home, curled on the floor throwing up. After three years of this, my mother finally agreed to let Serena take me to the “woman doctor. ”The gynecologist prescribed birth control pills to regulate my cycles and ease my cramps. Serena knew my mother would not approve and made me swear to hide the pills and never tell anyone. I agreed, wondering why anyone would admit to being a virgin who used birth control. It just sounded stupid.

The guests were arriving. I heard the scurry of footsteps above as my mother took her place on the sofa and Tej rushed to get the door. I wondered how many people had come this time. Harj and I had always guessed, making a game of it. It was the only variable part of the ritual and even then it hardly varied. I waited until I heard them go upstairs before peeking into the entrance hall to survey the shoes. I thought that the sensible shoes with the evenly worn soles indicated that one of our guests was an old lady shuffling through life to the end. The gold strapless sandals probably belonged to a new bride still happy to clip-clop through life, and the two sets of men’s dress shoes creased only at the toe belonged to young men whose gait was restrained by entitlement. I slipped my foot into the bride’s sandal and pointed my toes, disappointed that there was nothing Cinderella about it.

I walked up the stairs, avoiding the creaky third step, and slipped into the kitchen unnoticed. There I sat at the table, staring at the faded green butterfly wallpaper, counting wings. When my mother called for me, I lowered my head and walked into the room with a tray of water glasses, which I set on the table. My mother cleared her throat, looked at the tray and back at me. I picked it up, offering water to the men first, then to the young woman wearing wedding bracelets and lastly to the elderly woman, the matriarch whose loose caramel skin hung from her jaw. She refused and I set the tray down, waiting to be excused. Harj used to bring the tray in after she’d spat into each glass. But now that she was gone it was my job to offer the water and though I thought of her brazen act each time, I could never repeat it.

“This is the baby?” the elderly woman asked my mother, without taking her coal eyes off me.

“Yes, this is the youngest, Meninder.” My mother gestured towards me in a way that made me feel like I was a parting gift in a game show, something off The Price is Right. “She’ll be eighteen soon.”

The woman feigned a sympathetic smile as I joined my hands in greeting to the group. “Sat Sri Akal.” I offered her an obligatory half-hug. Just like my dadi, she reeked of mustard oil and mothballs.

“You wouldn’t even remember your father, would you?” the woman asked.

I shook my head, pretending that it was some kind of compliment. She inspected me for a moment, pushing my cheeks from side to side, tilting my chin up and down, before touching my head in blessing. I stood there long after she’d sat down, waiting to be excused.

My mother sat on the sofa, head tilted, eyes weepy and withdrawn. I wondered if she were acting or if her grief after so many years could be this real. I’d never seen her cry without an audience; her tears were of little use when there was so much to be done, so many to care for. She never even mentioned my father other than to say how different our lives were when he was alive, how different it would have been had he not died. I always waited on the edge of those sentences, hoping for more. But my mother never spoke of what preceded his absence and I was too frightened to ask. Until I’d discovered it for myself, I didn’t even know his name.

After learning to read, I’d returned to the closet and found, typeset on a half-empty container of penicillin: “Akal.” Years later, while reciting the morning prayer in Punjabi school, I paused on his name:

Ik Onkar Satnam Karta purukh Nirbhau Nirvair Akal moorat Ajuni saibhang Gurparshad Jap.

That was the only prayer I learned, and I repeated it several times before asking my Punjabi teacher what “Akal” meant. She told me that it meant “not subject to time or death.”

I whispered it sometimes—at night as I fell into the quiet possibility of dreams, and even at times like these when I needed something to mute the staid condolences that made loss less than what it was.

“So unfair… such a tragedy… he was so young, such a good man… ”

As always, my mother’s face fell, the distance of events blurring behind warm eyes. Her voice cracked, her tone dropping into soft gulps of lapsed grief. “They said it was an accident…there was an investigation…they were sorry…some of them even said it was his fault, but I know he was careful.” She spoke of it in fragments, allowing everyone else to complete her sentences with sympathy.

My father had fallen from the twentieth floor of a luxury high-rise apartment building where he’d been framing the walls. He was proud of his work and boasted about the complex’s amenities: air-conditioned units, an in-ground pool, a private park. It seems strange to me that this building existed somewhere outside our mention of it. That somewhere people were living in these air-conditioned units, pushing their blond, blue-eyed babies in strollers along the very sidewalk where my father lay dead; he’d died instantly. Sometimes I dreamed I was him. Sometimes I dreamed I was the fall. Either way I woke with a screamless breath escaping, my gut twitching into knots. I would lie back loosening them with thoughts of something, and then nothing.

But no matter how many times I dreamed of his death, I could not conceive of it; he was a myth and my mother was a martyr.

“If only he had a son… what can we do… it is kismet.”

I listened to them explain our entire lives away with one word. Apparently, it was my mother’s fate to be a widow with six daughters and our fate to become casualties of fractured lives. Though I struggled against such a predetermined existence, I knew that my sisters and I were all carved out of this same misery, existing only for others, like forgotten monuments that had been erected to commemorate events that had come and gone.

“No one knows why these things happen. Only God knows. Satnam Vaheguruji,” said the matriarch. She joined her hands in prayer towards the lithograph of Guru Nanak that hung above the brick fi replace, before falling silent, nodding to the beat of the grandfather clock that clicked like a metronome. Serena had given it to my mother for her birthday several years ago and since it was too large and cumbersome to fit in the hallway, it was left standing in the living room like a watchman. At the end of each month the pendulum stopped and the clock fell silent until it was wound again—a small reprieve.