Excerpt

Excerpt

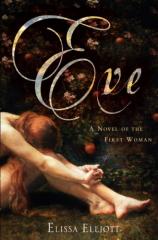

Eve: A Novel of the First Woman

Eve

I came upon my son's body by the river. The morning was no hotter or drier than usual, but as I crossed the plains between the house and the river, the wind kicked up the dust clouds, and I had to hold my robe over my nose. Dust clung to my wet face and marked the crooked trails of my tears. Behind me, the sky was the color of lettuce. The sand chafed my swollen feet, and my groin ached with the pains of Elazar's birth --- was it just last evening I had borne him? --- and my heart, oh, my heart's deep sorrow was for the travesty Cain had committed, then confessed to me like a blubbering child.

The body was not hard to find. The flies and vultures led me to him, fallen under the date palms, alongside the marshy river. His face was unrecognizable; Cain had seen to that. I don't remember if I was sad or grieving just then. I was more astonished than anything. I had seen animals killed, their throats slashed and their viscera splayed out on the ground, and certainly there were my babies who were lost. But nothing prepared me for the sight of Abel, my precious son, as still as a rock, his head bloodied and his neck arched back, stiff, at an unnatural angle. His eyes --- I realize now that it was a miracle they had not yet been pecked out! --- once full of his vigor and brooding and planning, were empty. They said nothing to me. Of course, Abel had said little to me ever since he took to the fields to tend his goats and sheep, but that is no matter. He was still my favorite. Is a mother permitted to say such things about her children?

I fell to my knees and threw my body over his. I lifted his head, cold and broken, to my breast, and cradled him there, as I had done so often when he was a baby. Fresh tears refused to come, which was strange. It was as though I had been thrown out of the Garden once again, rejected and abandoned, and, as only Adam can testify, they flowed like a river then. And where was Adam, my husband? Did he not care about our son, the one kissed by Elohim for his magnificent sacrifice? Or had Adam's deafness prevented him from hearing my anguished cries when Cain told me what he had done?

Softly, I sang the Garden song into my dead son's ear. I knew he would hear it, wherever he had gone off to. He had been the only one to understand its message and allure.

Abel's flesh was cold and clammy, and all I could remember was the vision of loveliness he was as a child --- soft chubby skin folds and eyes only for me. He was the first to bring me gifts --- poppies and ranunculus and clover, discarded feathers, and pebbles worn smooth by the river and carried down from the mountains. Cain would not have thought of it. He was too busy traipsing after his father --- digging, planting, terracing, and experimenting with anything green.

What sorrow there is in having children! At first, they tickle your heartstrings. They linger for your words, clutch at your skirts, feed on your breath, and then one day they lurch to the edge of the nest and flutter out. They never return, and the empty space yawns impatiently, demanding more. It is a never-ending ache, one that I continued to fill as long as I was able.

The vultures hissed at me and made loud chuffing noises. They spread their mighty wings and danced about.

"Get!" I shouted, half rising and waving my arms.

They did not budge.

Where was my Abel? Where had he gone? Was he wandering somewhere, looking for his mother? I wondered if he would weep at not finding me. I remembered Elohim's words to Adam and me, "For you are dust, and to dust you shall return," but still, I did not believe it, did not want to believe it. What good were our lives if, in the end, we simply returned to earthly particles?

To make sense of this tragedy, I shall have to go back to the beginning of that hot summer, preceded by the spring harvest and sheep plucking, when our family's unraveling began. Unfortunately, it is always in hindsight that we see our mistakes, like a wrong color in the loom or a foreign stalk in our fields, but by doing so, I try to account for my life and change that which I can. It provides a bit of solace.

Imagine then: The sun hung low and orange on the horizon, and Naava, my eldest daughter at fourteen years, was lighting lamps in the courtyard. There was the usual bustle of the men coming in from the fields --- Adam, my husband, from the orchards and Cain, our eldest son, from plowing. Adam, his robes caked with dirt and sweat, hung his arms across my shoulders and squeezed. "Wife," he said, pecking me on the cheek. "How is my woman?" He said this laughing, as though he had said the most humorous thing, and I grinned back, glad of his presence.

"Your woman is exceptional," I said.

On this particular occasion, Abel was absent. Frequently, he claimed that sleeping among his flocks gave him solitude and peace. Even after Jacan's discovery that morning.

Jacan, my youngest son, had been trembling when he returned at dawn from collecting water at the cistern. We could barely make out his words --- he was gulping in so much air. "Lion tracks," he said. "This big." His little arms stretched wide, and his fingers tried to frame a large circle in the air. "Abel," he said. "You should stay here today."

Abel had laughed and ruffled Jacan's hair. "Who will kill the lion if I sit at home?"

Jacan's eyes grew as round as onions, and he stared at Abel. "It's a big one," he said, doubtful that Abel understood.

Our tools and weapons hung on our courtyard wall --- adzes, sickles, scythes, hoes, throwing spears, daggers, and bows and arrows. It was to this wall that Abel went. He reached up for a slingshot and a bag of clay pellets. He turned to Jacan and said solemnly, "My aim will be true the first time." And towheaded Jacan went to him and hugged the huge trees of Abel's legs, Jacan's arms seeming so frail to me, like vines trying to find purchase. Oh, how I wanted to grab both of my sons and hold them tight!

Now, the long day over, the purple-gray evening skies pressed in from all sides. Inside the waist-high clay walls of the courtyard, moths and flies were drawn to the flames and danced shadows upon our faces. Aya, my crippled middle daughter, ladled meat into wooden bowls and plucked hot and steaming flat bread from the walls of the tinžru. I smiled to watch her kiss each piece of bread before she placed it on a platter. It was something she had always done from the time she was small and just learning to cook. I asked her about it once, and she said, "But, Mother, all things must be blessed. You said so yourself that Elohim blessed each thing He made." It was true. I had told her that, although I was beginning to doubt there was a personal Elohim who enjoyed my company. That had been a truth for the Garden, something sweetly shared between Adam and me.

Dara and Jacan were in their seventh year. As the sun slipped over the plain's flat edge, Jacan came running in from the river, knees churning, shouting, "Dara, Dara, Dara!" as though he were mad. He carried a box turtle from the marsh, and although I was convinced he had squashed it in his hand in his eagerness to show Dara, it was still alive and moving when he gave it to her. She squealed, of course, then grew morose when the turtle refused to poke its head out. "Mama," she cried. "Do something!"

I told her to be patient. "The turtle is probably frightened," I said. "Wouldn't you be too, if someone was throwing you about?"

So they hovered, squatted down on their haunches, and waited for the turtle's glorious head to emerge in the twilight. Such is the life of small children! It never failed to delight me, watching them involved with a task so simple, yet they remained so wonderfully curious and happy.

I do not recall what my family talked about that night as we filled our bellies, but I do remember what it was that made us all stop talking. There was a sharp cry in the distance, then a thud. To the north, maybe. Cain was the first to scramble up, because Adam, who was deaf in his left ear, hadn't heard. I'm sure we all looked like baby birds, mouths open, food suspended, for a moment, waiting, waiting, for another noise. What could it be?

"Father," Cain cried, as he rushed to the courtyard wall and disappeared into the edges of night.

Adam, accustomed to this disconnection between his inner and outer world, took his cue from Cain. He jumped to his feet, setting down his bowl. He reached for my hand and held it for a moment. "Stay," he said to us, and then he, too, was through the courtyard gate.

I daresay his command was ignored. Naava had a nose for adventure and for everything else out-there, a desire I could never quite understand. It was a compulsion that neither of my other girls seemed to possess. She rose, and though I called sharply, "Naava, wait," she dashed out too and vanished.

"What is it, Mama?" said Dara.

"The lion!" said Jacan, yanking on Dara's arm, then looking at me, fear solid in his eyes. "Abel!"

Aya's voice was calm and contemptuous. She had no time for silly conjectures. "Abel is in the hills. How could we hear his voice from here?"

Jacan's face registered confusion for a moment, then he rallied. "Maybe he was on his way home because he was lonely, and the lion attacked him." He turned to me. "Father will save him, right?"

I waved his worries aside and began collecting the bowls to scour with sand, but Jacan's words gave me goose skin. What would happen if I lost my son?

I tended a small collection of burial mounds in the garden that Adam had planted for me --- a son whom I had borne before his time, a daughter with a malformed head, and another daughter who had emerged, dead, with knots in her cord --- but this was different. Abel was a grown man, with curls of hair on his chest and a gruff voice and somber moods. He did not belong in the ground, away from his family, silent, covered with dirt and thistle and mesquite.

Because I have given life to each of my children, I love each one. Cain --- for his ingenuity. Abel --- for his sweet ways. Naava --- for her feistiness. Aya --- for her resourcefulness. Jacan --- for his tender heart. Dara --- for her compassion. But in times like these, a mother's mind flashes to --- oh, think me not cruel! --- whom of her children she would most like to hold fast, if given the choice. Although I strive to treat each equally, my heart cannot be led like Abel's sheep. It is stubborn and goes where it likes. I do not find any solace in this truth; in fact, it causes me much turmoil.

My love comes in shades of color. There is a bright pulsing red, and there is a weakly washed pink. I do not know why; I only know that it is so.

So, truth be told, it would have been Cain I would have sacrificed, if I had been forced to choose. Cain always grappled for his significance with the universe, his superiority over all of us, even his disgust with us. It was as though he were made in the starry heavens yet housed in a fragile warm shell that was susceptible to injury and ache and decay, and the frustration for him was too much.

As a child, Cain tortured and killed frogs, birds, and lizards. He baited the ducks at the river by hooking a bit of bread and waiting for an unfortunate one to pluck at the morsel and swallow it. He sliced open their throats, then cut them apart, determined to find out what made them breathe or walk or fly.

Everything was a torment when they were boys, even such a small thing as splitting a pomegranate between him and Abel.

"You've given him more," Cain would squeal in fury.

"Here's a bit more then, from mine," I would say, and give him another section.

"I want it from his!" Cain would say between clenched teeth.

"That's enough," I would say.

From Abel, there was nary an unkind word or threatening look.

He was a summer rain.

That night, I quelled a gasp in my throat. Not Abel, please not Abel, I prayed. I prayed to the One who had formed us in the Garden, the One whom I had talked with there, and the One whom I did not believe cared for me anymore.

The reason I prayed was simple: I prayed to Him because it was the only thing I could do. True, my energy was irrational and ill-founded, but nonetheless I invoked Elohim my Creator.

Hear my cry, O Elohim, and give heed to my prayer. I shall shout Your praises to the sky. Let me not be ashamed.

And so it came to pass that, as I prayed, the winds of my heart blew no more. It was quiet, and I sat to hear what He would say to me.

His words never came.

Naava

Eve closes her eyes and rests. She's been holding her head up this whole time, straining to make herself heard. Her hair is white now, splayed out like a sun-bleached starfish upon her pillow.

Naava places a cool cloth on her mother's forehead. "Shhh," she says. "Lie back." She stares at Eve's face, the bear-clawed scars on her right cheek, the irregular brown spots on her hands and arms, the deep lines in the skin around her eyes and lips, and the frown cracks between her eyebrows. Naava wonders why her mother is so dramatic, so wrong about the past. Is it possible that two people can experience the same thing and come away with two different stories?

Naava takes Eve's hand, knobbed like a piece of gingerroot. She traces the swollen rivers of blood in Eve's veins, shutting them off, then letting them rush forth under the skin. She remembers: sitting with Aya and the younger children by the pond, under the shade of Eve's beloved Garden of Eden tree, telling Eve's stories to one another in the heat of the afternoon, while the asps warmed themselves and the bees buzzed above their heads. They played the parts --- the serpent, Eve, Adam, even the cherubim and the wavering lights. Once, Aya insisted they all chant to Elohim, asking that they be able to return to the Garden, to see where their mother and father had come from. Elohim answered in a breeze; His words sounded singsongy and soft. What's done is done, my children. His swift reply only encouraged Aya in her attempts at further conversation; it did the opposite for Naava. Naava was petrified. Voices should come out of people, not out of thin air. Really, she wasn't even quite sure she'd heard anything at all.

Naava felt this: Eve knew so little of what had happened because she saw only what she wanted to see and loved only what she wanted to love. She herself had said this in so many words, hadn't she?

Eve: A Novel of the First Woman

- Genres: Christian, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 432 pages

- Publisher: Delacorte Press

- ISBN-10: 038534144X

- ISBN-13: 9780385341448