Excerpt

Excerpt

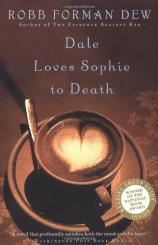

Dale Loves Sophie to Death

CHAPTER ONE

DALE LOVES SOPHIE TO DEATH

Every summer Dinah was sick in this house she rented. She lay in the double bed alone, amid a jumble of Kleenex and the mail and the morning newspaper, and she did not change the sheets until she felt well. Sometimes two weeks, sometimes three. The light shot into her room in the morning, so that her eyes would ache, and then it shifted and faded as the day wore on, and through all these changes of light she drifted in a fog of sleep and waking and the children's bodies buffeting against her bed. Propped up on pillows, she could see her three children, through the tall branched shrubs beyond the windows, as they ran around playing or fighting. But she would lie dazed and sure that they could get through the day with only her occasional direction. David, the oldest, was always herding the other two, it seemed; when she closed her eyes, the red imprint of his ushering arms in motion shuddered through her mind as her thoughts drifted away from the actual image.

Her mother often stopped by on the way home from her office in nearby Fort Lyman and brought Dinah food from the deli or some other takeout place. Today she brought a barbecued chicken the size of a dove, and Dinah sat in her bed and ate it with her fingers, sucking the knobs of the little drumsticks like candy. Her mother sat on the vanity bench, at an angle not quite facing the bed, and talked desultorily, because the disarray in which Dinah wore out her illness dismayed her. It had always been assumed in Dinah's childhood household that illness was a weakness of character, a burden to the entire family, and, above all else, being ill was considered a sly trick. So Mrs. Briggs pushed her straw-colored hair behind her ears impatiently as she sat there required to hear just how Dinah felt. Dinah said she felt feverish; she said she had a sore throat and aching ears. Her mother sat in the early twilight, covertly eyeing herself in the mirror, and she sighed when she noticed that Dinah had sunk down into her pillows once more, leaving the little chicken carcass stripped bare in its greasy wrapper by her side. She thought she bore up very well under these illnesses of Dinah's.

"I'll take the children on with me, then," Mrs. Briggs said, and she collected the parcel of chicken bones from the bed and went to look through the window to see if the children were in sight. Dinah lay unmoving and with her eyes closed. Mrs. Briggs was not a good cook, so she considered the frozen and canned options for the children's dinner. She also considered scrambled eggs, which were healthful but which no one ever finished at her house. Dinah had told her the reason for this with patient tact, and had advised her about better methods of preparation, but Polly Briggs had never heard all that her daughter said. She still heated butter in a skillet and broke the eggs directly into it, cracking the shells on the aluminum rim of the pan, and then she agitated them as swiftly as possible; they always appeared on the plate as though they had been marbleized, with the yellow and white running separately throughout. Also on the plate she would place one piece of toast with a pat of butter squarely in its middle, to be dealt with however one might wish. These things were gestures: the eggs broken, not just boiled, the toast prebuttered—even the butter itself, rather than margarine. They were quite generous gestures from a woman who cared not at all about food but had a melancholy interest, generally, in the people she fed, and especially in these children to whom she acknowledged a connection.

When the house was empty and there was no sound from the yard, Dinah opened her eyes and regarded the room. This year it was hung with more recent pictures of the family who owned the house. All told, in the past eight years she had spent close to twenty-four months in this house, and although she had never met the owners, she felt that she and they had established a certain intimacy simply by virtue of sharing the same paraphernalia of everyday life. She used up rather than discarded the half-empty jar of mustard in the refrigerator, for instance, and in her view that was a very solemn intimacy; the first summer she would have thrown it out in horror. And, of course, this intimacy in absentia bred its own sort of expectations; Dinah expected to find evidence each summer that life in this house continued during the winter just as she imagined it. She looked with interest at the new photographs hung in the bedroom, because she knew these people—not all their names, but she knew how they were growing up or changing.

This summer there was a new picture of the daughter of the house, whose other photographs, scattered here and there through all the rooms, dated back to her infancy. This current snapshot, enlarged and framed handsomely on the wall opposite the end of the bed, showed a very lovely young woman frozen in the upswing of a jogging step as she ran through a prosperous-looking neighborhood. Dinah studied her drowsily, thinking that she must know her. The girl looked as if she would be interesting to know, with her hair flying around her face and a cast-off sweater tied around her neck by its sleeves. It was possible that they had passed each other at some time or other-at a state park, perhaps, or some restaurant. A public bathroom maybe. Dinah was drenched in her luxurious illness—flu with fever. She felt she glowed inside and out with this lovely, gentle radiance of almost 102 degrees. Her head throbbed independently, so she could objectively consider the shell of pain encasing her mind. She swallowed two aspirin, and when they took effect she allowed herself to sleep until the aching of her head and limbs woke her automatically. When it did, she just lay there in bed, at home, considering her surroundings.

At the beginning of each summer, Dinah and Martin Howells drove west from the Berkshires, where they lived, with their children in the back seat, and in two days' time they were in the lush farmland outside Enfield, Ohio. When they had first rented a house in Enfield, eight years earlier, they had had only David, then two years old. By now, the children thought it was the only place to spend those long weeks when there was no school. Dinah felt that these modest hills and voluptuous, rolling fields of corn and soybeans were essential to the very stability of her being. She had such a familiarity with this countryside that it didn't occur to her to miss the occasional sweeping view of valleys one happens on at high altitudes in New England. Instead, she hugged herself there in the front seat the moment she became aware of the vast, light-filled landscape proceeding endlessly in every direction. She felt as lighthearted, always, as a claustrophobe must feel upon emerging from an elevator.

On the first morning in their rented house Dinah was always affected with a reckless, thoughtless euphoria. She would make her nostalgic pilgrimage through the rooms, moving dreamily, and she would open all the curtains so that nowhere could there be found a somber corner. "Oh, my God! It's so good to be somewhere where I can pull up all the shades!" She would insist that everyone agree with her. "Isn't it? Don't you feel good?" She would not acknowledge the hesitation with which Martin always embarked upon this summer venture. She didn't think of his saying, "But why do you do this to yourself year after year?"

Dinah had no answer to that. It was only that in West Bradford at Christmas, when a card arrived from the Hortons, the owners of the house in Enfield, she looked out at the winter and began to entertain thoughts of summer. Those thoughts did not run deep but were like photographs flashing through her mind. This winter, on the day the Hortons' card arrived, Dinah and Martin had happened to go to lunch at a pleasant restaurant, decorated with an abundance of greens and a large blue spruce standing in the foyer unadorned except for hundreds of tiny white lights. There were flowers on the tables, and other people's children were being allowed to wander around the room and stretch their legs while their parents lingered over coffee. Everyone was well dressed, even with a certain dash, and the stark landscape—the sky, dense and heavy just overhead, the boundless white ground—only emphasized the singular feeling of goodwill Dinah had toward the other diners. But with all this the atmosphere just brushed over Dinah's senses; it did not permeate her thoughts, because she had tucked the beautiful Caspari card from Adele Horton into her purse; she was thinking of what it said, and her mind had become entangled with images of her summer household. The message was nothing, really: "Wish we could share with you some of this lovely apple chutney I've put up for special friends. Will certainly leave some for you if you take the house again this summer." But Dinah had found such a homely notion-to share some chutney—stupefyingly seductive. She could not help but sit there in a restaurant in New England with her husband and consider the life being led right at that moment in that house in Enfield. Such an intense life—so full that it could not be contained in ordinary spaces and overflowed in little notes and letters and photographs inscribed with cryptic messages that even fluttered from the cookbooks Dinah sometimes pulled down from Mrs. Horton's shelves. More letters were stuffed haphazardly between the books in the living-room cases, and curling photographs and mysterious souvenirs filled every extra drawer. Quaint drawings by children or friends were carefully framed and hung in odd corners. It seemed to Dinah that so much life went on there that her own existence could not compare. She was beginning to think that the five of them—she and Martin and the children—were simply too sparse a group to generate such vitality.

But she knew that Martin loved her and she him. She understood his intentions when he asked her why she put herself through those summers. Well, she could never justify it; she could only raise a hand in a gesture of exhaustion—and exhaustion was all she felt when she thought to examine her motives—to reply halfheartedly, "Oh, you know the children love it. Don't you think it's good for them to get a feeling of family?" She didn't even glance at Martin to see the look of doubt come over his face. He knew the dubious nature of what family feeling there was since Dinah's parents had divorced and her father had moved into his own house, directly across the street from the Hortons'. "Well," she would offer, "things just aren't settled there yet to my satisfaction."

And so summer had come, and here she was once more. But, upon their arrival and her inspection of the familiar rooms, she knew her insistence that Martin share her enthusiasm for this place was unkind. She knew just how unkind, and she lay in bed letting herself be entirely given over to her private admission of guilt. With her head sunk down into her soft pillows, and her whole being made fragile and abject by the mellow, flu-induced ache of her muscles, she acknowledged her cruelty. Perhaps Martin had not felt it. Oh, no. This year, before he had had to leave to go back to teach his summer classes, they had really argued. Dinah tried concentrating on her illness once more. She thought about her various aches, and she pinpointed the fact that the way her ears felt could not really be called pain—more like a sore itching extending down into the base of her throat, so that it hurt to move her tongue. But the thought of the argument stayed in the forefront of her mind despite her, because it was not quite accurate. They had not argued; Dinah had attacked him, and now the thought of it made her flinch.

For the first two weeks of summer Martin and Dinah were always stranded together with the children in the rented house, without many diversions. During the long New England winters, when Dinah reviewed these times together, she said to herself that they were idyllic, but that had never been exactly the case. Their time together had generally been very pleasant, but there was always the stray mosquito or a child's hurt feelings, and there arose a peculiar tension between her and Martin as lovers. She felt a certain chafing at the constraints of being at once a daughter and a wife. But, really, she considered herself to be in great comfort, with her immediate family right there and yet situated so that there were no difficult expectations of herself that she must meet. It was privacy Dinah cherished, and it was the lack of it that she complained so bitterly about in West Bradford. In fact, in Enfield what passed for privacy was the absence of it altogether. So well did all the inhabitants know each other that they had long ago passed the point of pretense. It would have been futile in any case; it would have been absurd. And, therefore, very little was considered scandalous in retrospect-that is, if even just a year had passed since it happened. Very little was even considered remarkable. And so, coming back gave her an ease that she could never experience elsewhere; she understood the place so well.

She and Martin spent the days strolling through the town, eating their dinner at the picnic table under the pin oak in the back yard, and visiting with her family and good friends. They were only three blocks from her mother's house, and only one and a half blocks from the exact place in the sidewalk where Dinah had fallen her first time out on roller skates and chipped her front teeth. They were only a ten-minute walk from Dinah's grammar school, and only a ten-minute ride from her high school in Fort Lyman. As they walked down the shady streets or sat at a meal, Dinah would often point out these remarkable coincidences to Martin and the children, these astounding circumstances of her own childhood. Everyone would walk along the sidewalk with her and regard the tree in which Alan Brooks had built a tree house one summer. "And he's dead now," Dinah would say, bemused. "Buddy wrote me that he died in New Orleans." It was a mystery. But the children wouldn't think of what she was saying, although possibly these words would one day be to them one of those bewildering facts about one's parents that everyone accrues over the space of a childhood. Her children might one day say, "And my mother fell down and chipped her front teeth the first day she ever tried to roller-skate." No doubt they would see in their mind's eye the very spot in that little village where it had happened, and having gained their independence at last, with the usual struggle, they would be overwhelmed by the poignancy of having had so unexpectedly vulnerable a mother.

Or maybe they would never think of it again. Maybe they would think of the day Sarah had been lost, or the morning their grandmother had reached down David's throat to retrieve a piece of candy that would have choked him to death. To think of it! He would not have existed past that moment. They, too, experienced the most crucial turning points of their childhoods here. And how could they not? All winter, when the snow lay around their house in West Bradford, Dinah would urge them, "Wait, just wait until we get back to Enfield this summer." When the children raced up and down the stairs, not holding on to the banister and making too much noise, Dinah would follow after them in great aggravation. "For God's sake, can't you wait until we're in Enfield, where there's no snow? Then you can go outside and run around." And even though the children had seen pictures of their mother when she was a child playing in front of their grandmother's house in the snow, and even though they spoke on the phone to their uncle and grandmother at Christmas, when there was much talk of snow for want of other conversation, David and Toby and Sarah assumed that there never was any snow in Enfield. Enfield was a place of hot sun and light and long summer days.

The trip itself, however, always proved to be a terrible strain on the general good nature of the family. After two endless days on the road, all three children grew edgy and cross. Bribes and diversions no longer pacified them. This year, even Sarah was old enough to join in the melee.

"Toby's looking out my window, Mama! He's looking out my window!"

"Toby's sitting in the middle. What can he do?"

"I didn't look out his window when I was sitting in the middle!"

If only they were old enough and wise enough to remember to look out for the danger signals. Martin and Dinah recognized the signs forewarning each child's anger or distress—they knew their children so well. And the children knew their parents equally well, but they weren't so versed in the art of survival. From their vantage point, they could only see their mother's hair swing gently from side to side as she shook her head just slightly, in a silent conversation with herself. One corner of her mouth was pulled askew; she crossed her arms and grasped her elbows tightly and stared out the window.

"Oh, Mama, Toby's..."

And then Dinah half turned in her seat and stared at them in fury, and all three children were immediately filled with remorse.

"Well, damn it, Martin, stop the car!" she said in deadly, measured calm. "Stop this damned car! There's only one answer to this!" Her voice was so ominously low that the children looked away from her in nervous discomfort. And Dinah herself, with the blood beating in her ears, was not paying attention, either. In her rage she chose not to see the effect of her anger. "We will just put out Toby's eyes! We will just, goddamn it, put his eyes out!" She turned to stare at them more directly, and she gripped the back of the seat with one tense hand. At last, her voice rising, she said, "Will that make you happy, Sarah? Then, I swear to God, he will never look out of your window again! That should do it..."

Martin, of course, had not stopped the car and, in fact, was driving on placidly enough. "For God's sake, Dinah..." he finally put in. "Look! We're getting close," he said to the children. "See what landmarks you can find."

The children gladly followed his suggestion. Sarah ground the heels of her hands into her eyes to keep from crying, and the other two observed with relief that their mother turned back to look straight ahead after directing one incensed glare at their father. The children did not take this too much to heart, though. Even Sarah, at age four, had already perceived enough to know that her mother would die—really would die—before she would put out Toby's eyes. She quite rightly absorbed her mother's outburst as a rebuke to herself, and she continued to wipe at her tears furtively, and so she missed the first major landmark.

Toby spotted it, through Sarah's window, and he bounced in his seat. "I see Aunt Betsy's! There's Aunt Betsy's!" They came down the long hill and passed the bizarre diner once known as Aunt Jemima's, which had for years been a towering black mammy whose brick skirt housed a quite ordinary bar-and-grill. Now it was Aunt Betsy's, and the huge head loomed over the highway hideously pink, with gray rather than black hair escaping from the immovable bandanna.

For a while, all their tension was dispelled, and it was Sarah who, having knelt on the seat to repossess her window, shrieked to them all, "Look! 'Dale Loves Sophie to Death'! There it is!" Even though she couldn't read she knew it well. "There it is! 'Dale Loves Sophie to Death!'"

Their station wagon passed beneath the railway bridge on which this legend had been emblazoned ever since they could remember. The children were finally able to believe that they were indeed close to home. And David started up the song:

A hundred bottles of beer on the wall,

A hundred bottles of beer.

If one of those bottles should happen to fall—

Ninety-nine bottles of beer on the wall.

Family theory had it that when the song was done, and there was only one bottle of beer left on the wall, they would be home, although this had never yet been the case. But everyone was relieved, because when the song was done they would be close enough. Martin drove over the narrow back roads smiling to himself, and Dinah noticed.

"What?" she asked.

"Oh, I just have always liked all this. It's genuine Midwestern-tacky. Aunt Betsy's diner. And things written all over the water tanks and bridges in huge letters." He glanced at Dinah to smile at her in what he meant to acknowledge as an admittedly smug conspiracy. Not for a moment had he imagined that in being so blatantly provincial he did not also belittle himself. But Dinah was looking rigidly out the window.

"Well," she said, so that he could hear her but so that the children in the back seat continued their song, "you think that 'Dale Loves Sophie to Death' should be typed, I suppose. And tacked up on a little bulletin board in Jesse Hall. You know, there's something about real, honest-to-God emotion-I mean real things that real people go around feeling—that you just never can understand. I mean, 'Dale Loves Sophie to Death' is not exactly a lower-case sentiment! I don't think you know a damned thing about that! You just go mincing through your life with almost nothing but lower-case sentiments!" She made movements with her hands and her head, like a person taking small and hesitant little steps, and she pursed her lips to indicate her immense disdain.

He had been watching her with a startled expression, and when he had taken it in, he laughed at the idea of himself, rather thickset and solid, mincing into his various meetings, teaching his classes, mincing through his days. And she laughed, too, but it made her even more angry to find herself amused. She saw as well that Martin was wounded, and it made her so uncomfortable that she returned her gaze to the countryside that swept by outside her window. They both sat there in the front seat bewildered by her fury. They knew that she had been unfair, and Martin was not hurt by what she had said—he couldn't imagine that it applied to him—but he was hurt because she was so angry.

The day after their arrival, Martin and Dinah and the children abandoned their unpacking in the afternoon and walked down through the village to Dinah's mother's house. By now, it had become customary that a party of sorts would come together that evening, and Polly had made a routine of the preparations. She had bought a ham the day before, and Dinah stood at the counter scoring it in a diamond pattern and rubbing it with brown sugar. After she scored it, she would decorate it with rounds of sliced pineapple and maraschino cherries and put it in the oven to glaze. She looked out at the twilight approaching and was struck with sudden petulance.

"This is a little like decorating my own birthday cake," she said to her mother, who was transferring cartons of take-home potato salad to a cut-glass bowl. "Maybe you should line that bowl with lettuce leaves or something first, Mother. Don't you think?" But then Dinah thought of her father leaving the table in a cold rage one evening with a face like ice, saying, "Well, I don't know. Maybe we should just rent out our kitchen or turn it into a spare room, for all the use it gets." Dinah had been aware then that some key element of her parents' alliance was being defined for her when her mother made an eloquent sweep of her arm, palm upward, in a helpless gesture of apology and bewilderment. But her father had already left the room. With that in mind, Dinah turned to look at the potato salad once more. "No, it's fine. We don't know for sure that anyone will be coming by, anyway."

But her mother wasn't really listening. Polly had finished with the cut-glass bowl and had deposited all the little paper cartons in the trash. Dinah did regard that salad with dismay, however, because, as usual, it looked even more gelatinous and unappetizing in the pretty bowl than it had in its own containers, and summer after summer this had perplexed her. Her mother leaned against the counter, resting her weight on one narrow hip, and smoked a cigarette. She gazed through the window with one eyebrow slightly raised, in an attitude of complete indifference to her surroundings. Dinah had come across her mother thus transfixed so often that she no longer perceived it as a mystery. She watched her for a moment in admiration, however, because, caught in the dusky light, her mother—worn out, with her flesh drawn and lined and the skin at her jaw beginning to hang a trifle loosely from the bone—was lovelier than she had been when she was younger. The bare bones of her mother were coming to light, and Dinah thought that Polly was the only woman she knew who could combine a certain brittleness with an air of languid grace. But Dinah no longer puzzled over what her mother might be thinking.

On the porch, the children built card houses with the incomplete and abandoned packs of cards they had ferreted out of obscure drawers here and there around the house. They weren't building with much success, however, because the floorboards were so worn that they didn't afford sufficient purchase, and at crucial moments the bottom cards slipped out from beneath the upper construction. Polly's house resembled her person, by now. Even though her business was interior design, and she was good at it, her own house had been left to its own silent transmutations. The bare bones of the house were also coming to light, so that the walls seemed only a thin veil over the basic construction, and the furniture had a delicate look of age.

Martin sat at the other end of the porch with a newspaper resting on the knee of one crossed leg and talked with Dinah's brother, Buddy, and with Lawrence Brooks, who had come across the lawn from next door, where he had lived all his life. Now that house was Lawrence's own house. He was a lawyer and no longer just a child next door. Lawrence's wife, Pam, idled over with their two-year-old son propped on one hip and sat down next to Dinah, and they began to chat.

As she listened and put in a word now and then, Dinah stared out at the communal lawn shared by the Brookses' and her mother's houses, which sat at right angles to each other. She studied the myriad tiny crosshatched branches of the flowering bushes that grew untended around the stone patio in the center of the yard. She hadn't much to say to Pam. Pam was so young, and her son seemed to take up both of their energies. The two women talked about the little boy, though it was apparent to each of them from the timbre of the other's voice that neither meant to or wanted to.

At the edge of their conversation, Dinah heard David badgering whomever he could find to come and play Monopoly with him, and Martin, who would do almost anything with David, finally got up, and the two of them went to find the board. Buddy and Martin and David and Dinah's mother settled around the card table at last and divided the money while Pam and Dinah went to mix drinks and set out dinner. Lawrence, still seated at the darkening edge of the porch, opened Martin's discarded newspaper and kept a casual eye on the other children.

This was the house in which Dinah had grown up, and her childhood was so fascinating and mysterious to her in retrospect that each room was of great significance. Even the unique and musty scent of the house, a scent like no other, tantalized her with the possibility of an important revelation. So this first night back in her mother's kitchen she could not abide the company of the innocent Pam. Dinah set out food at random and with no show at all of appreciation to Pam, who could only follow her about and try to help. And from the porch the sounds of the Monopoly game being laid out and getting under way made Dinah clench her teeth in apprehension, because David was, to his parents, like a rare gem set between them. He was not necessarily the nicest of their children, nor could it yet be said that he would be the most handsome, but he had been the first. It was not even that they loved him best; of course, he was not always lovable at all. It was just that beneath the surface of their consciousness there was an awareness of David that registered every shadow and nuance of his altering sensibilities. Their curiosity could never be assuaged by anything he might reveal about himself. They yearned after whatever it was that was at the very core of his personality, so puzzling to them was his blossoming independence. Dinah could hear his clear voice babbling above the others, and she noted the effort he made to suppress the keenness he felt for the competition. Listening to the progress of the game was a little like refusing Novocain at the dentist's; it kept her on edge in anticipation of a painful shock.

She turned to Pam and smiled at her. She picked up Pam's little boy, Mark, who was getting into everything, and feigned interest in him. But after a few moments of this she was overtaken by unease, and she realized that she could not be gracious tonight. She thought she felt the beginnings of a cold amassing like clouds behind her brow, and she was anxious. She took her drink out to the patio, though the air had grown chilly, and sat at a distance from her family and friends. Here she was once more, and she sat in a lawn chair expecting the childhood comfort of early evening, with grownups nearby talking over their drinks, to descend upon her. She watched with care to see how the darkness encroached upon the margins of the yard; she impressed upon herself the phenomenon of the intricate tracery of the foliage losing its distinction, so that each tree and each bush became a shaded mass. She evoked all these familiar impressions, but the accompanying sensation of nostalgic pleasure did not surface. No mellowness spread like the warmth of alcohol through her limbs; she found she could not call up the renewed faith that all is well, that all will be well. In fact, all she was feeling was increasing irritation. The image of that ham stuck fast in her mind. There it sat, bedecked like a Christmas tree, waiting to be carved, and only Pam and her baby to attend it. Where were the grownups? So she roused herself and went back to the house to set about the serving of dinner.

A second circle had formed around the card table to see how the game was progressing, and so she, too, stopped to watch. Immediately she was aware of her son's fragile courage hanging so vulnerably in the air when she caught sight of his shining eyes and large gestures of bravado. He made a great show of cavalierly paying a debt. Buddy sat across from him, leaning back in his chair, accepting David's money with a grin and carefully sorting it into the proper piles. "I'm gonna clean up! Oh boy, I'm really gonna clean up!" he said with mock greed. But Dinah watched him as only a younger sibling would, knowing that Buddy didn't play games except to win. He was flicking an imaginary cigar between his fingertips and patting his stomach with the satisfaction of a contented businessman. David relaxed and smiled at him with unassumed pleasure; Buddy's pantomime seemed to assure him that this was only a game. Dinah could scarcely bear it.

Her mother sat with all her bills gathered into a pile that she held in one hand and ruffled absentmindedly with her thumb. She rolled the dice with seeming indifference. Who could tell if it was real? She was looking out into the yard when the dice fell, and she looked around at the numbers on them almost in surprise and reached for her cigarette. She moved her token to St. James Place and completed a monopoly, the first of the game, and David sat up on his knees in excitement to look over the board. "Wow! You got the first one, Polly!"

"Oh, yes, I guess I did," she said, paying out the money for the deed. But she would win as usual, Dinah knew. Polly couldn't lose at games, playing, as she did, with tremendous detachment and no thought given to bribing her luck, while her competitors silently tried to strike up bargains with God or fate. Polly would finally wander away from the game, uninterested even in her own victory. It was maddening.

David rolled the dice and landed on a railroad. He had two already, and now was beside himself with delight. "I'11 get you, Uncle Buddy! Now I'll really get you if you land on me! You'll have to pay me a hundred dollars. A hundred dollars!" Buddy covered his face at the grim prospect and sadly shook his head, and Dinah understood with gratitude that her brother was using all his charm to align himself with David, so that David could withstand the suspense of this intolerable game.

But Martin didn't play games, didn't know about games, really; he was so innocent of some things, and he was watching his son with an air of censure. Dinah felt suddenly as though those four people were frozen in the moment: her mother abstracted, Buddy all pretense, Martin the epitome of thought and propriety, and David open to anything, ready to head in any of their directions. And, sure enough, Martin frowned across the table at his son. "Don't be so rude to Buddy, David. You shouldn't gloat. That's one of the first things to learn about playing games. Otherwise, you'll hurt people's feelings."

"Oh, Jesus," Dinah said. "What a pompous ass you are sometimes, Martin. Great God!" And in a frenzy of frustration at them all she glared into their crestfallen little group. "Not one of you—not a single one of you—has any idea how to play this asinine game!" And she stalked from the room while they all stared after her.

"Dinah, you talk like some kind of sailor," her mother said, mildly. Dinah left the room in a fury, going straight to the kitchen, and instead of carving the ham into careful slices, she hacked it savagely into chunks that were scarcely manageable when eaten buffet-style on paper plates.

Two weeks later, when she drove Martin into Columbus to catch his plane back East, she considered various ways of apologizing to him for the foul and dismal temper she had vented at him over the past long days. She looked at his clean head, which she so loved, silhouetted against the car window, and she wanted to weep at the misunderstanding between them. She was sure she was coming down with a flu, and she simply couldn't think. There was no one, no others but the children, to whom she was more tied. But then, as they passed through the familiar fields and the little towns, she could not think how to isolate that misunderstanding; how could she name it?

Now, as she suffered all the physical miseries of the flu, she also ached with a regret at having left a chink uncovered in their carefully constructed foundation of experience and tolerance. She lay in bed staring at the walls, awash in something similar to guilt, only much worse. There was self-loathing, there was fear, and, oh, there was a kind of homesickness she felt at this slight loss of herself, because she might have weakened a profound connection.

She looked at the picture, directly across from her, of that girl running. She was growing more beautiful each summer, and Dinah studied her intently. The girl's endearingly long upper lip was almost ready to smile, but she was clearly giving no thought to the camera. Caught in midstride as she was, she was involved only with herself; she was thinking about her next step. Dinah studied the picture for a long while, so that by the time her fever returned and she began to drift into a light sleep she had become convinced that she did, indeed, know this girl. The girl was Sophie, beloved of Dale, loping steadily toward him, or perhaps away from him, through that neighborhood, to be loved or not to be loved to death.

Dale Loves Sophie to Death

- paperback: 227 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316890669

- ISBN-13: 9780316890663