Excerpt

Excerpt

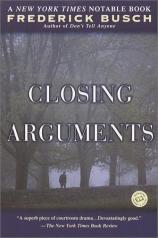

Closing Arguments

Chapter One

Opening Argument

Let's say I'm telling you the story of the upstate lawyer, the post-traumatic combat stress, the splendid wife, their solitudes and infidelities, their children, his client with her awkward affinities, the sense of impending recognition by which he is haunted.

You can see me, can't you? You can see me in my office after hours, after dark, after dawn. The bottle of ink, the sharp-nibbed pen, the pad of yellow sheets with their line after line.

Stand and be recognized a sentry was supposed to call to anyone dragging in after dark. Maybe they'd be on the end of a long-range recon. Maybe they'd be sappers with mines. The perimeter people at Da Nang were Marines, and they were disciplined. They almost always shouted something before they tried to kill you: the best defense is a good story.

Haunted is the word to use, though. His story's about his wife, Rochelle, her need to publicly acknowledge his war, the recognition he will suffer if she does, and how she'll suffer worse. The threat to him is real. The deception is real. This is a very cruel story, you know.

If one word is haunted, another is sad. Use it for his wife and kids. And betrayed, because the innocent can never be protected.

And numerous other words that in the course of this testimony you will be asked to consider.

Family

It was February, very cold, lots of snow. It warmed up during the day and rained, then it froze again: glass on top of slush. I slid my way home, it was ten or eleven, and in the kitchen I found Rochelle sitting over a cup of coffee the way people huddle at a fireplace. Jack was leaning back in his chair, sitting across from her, tilting so far back you knew he had to fall. Those big feet were planted in their unlaced moccasins, his socks were pooled beneath his ankle bones at the tops of the shoes. His face was tight. Tight. Schelle's was wet with tears. I didn't need filling in. I knew it. He'd been orbiting further and further. She'd been handling the distance. That's what we tell each other. Handle it, we say. Which means you don't take it personally that your kid is insulting you and pushing you and standing in your eyes. Because he needs you taking it personally so he can pop off.

I sat down in my coat. I waited in the silence a little.

"Hello, Dad," I said. "Have a long day?"

"Yeah, Jack," I answered myself. "Pretty tough. But I'm glad to see you, kid."

"Me, too, Dad," I said.

"Don't," she said. "Really. Don't."

"Can I do something?"

Schelle said, "Jack? Can you think of anything?" His large, wet, very dark eyes looked over my shoulder at nothing. I said, "Mom spoke to you, Jack."

With no expression, he said, "I didn't hear the question."

"I think we're trying to find out why you're angry. Am I right, Schelle?"

She nodded, reluctantly. I knew how much she wanted me out of this one.

"I can't remember," Jack said.

"Is it about something Mom or I did?" Rochelle said, "We've pretty much been through this, Mark."

"You could answer me," I said. I was gentle. "Excuse me?" Jack said.

"Why are you being so evasive, hon?"

"Me?" he said.

"Yes," I said gently.

"What was the question?"

"Are you on drugs?"

"That's a new question," he said.

"Are you?"

Schelle said, "Mark."

"I don't think so," Jack said with exaggerated care.

When he was younger, we'd been through one like this, we were homing on the end of it, and he said something mean, what a parent calls "fresh" before he clips the kid. We were standing up, I remember. Upstairs in the hall, I think. I put a four-finger jab, the hand rigid and fingers locked, directly into his solar plexus. He started to double, and I said, Stand up. I remembered that at the table, trying to get him to talk. Stand up, I remembered saying. I must have said it right. Because he stood. He kept wanting to collapse. His face was very white. His eyes got huge. He wobbled. I told him, The breath'll come back. You won't die of it. You'll get your wind back. You stand and mind your manners, I told him.

I was thinking of that while we sat at the table. My face must have showed it. I must have showed whatever I felt. I thought I regretted what happened. I think my face showed something else. Because Schelle said, "Mark."

She said it the way I would tell a dog to heel if I had a dog and trained it.

"Mark."

I said, "Jack." I sounded gentle. "Jack, it doesn't feel like we're functioning here. You know what I mean?"

He looked at me.

"I think you do," I said. "You're a troubled boy. You maybe need some help. Mom and I are willing to find it for you."

"I'm not going to a skull doctor," he said.

"Psychiatrist. Psychologist. Some kind of professional person who can help you," Schelle said.

"I'm--listen to me: I am not going."

Schelle said, "Darling, we don't think you're, you know, crazy. It isn't anything to do with words like that. It's for help. It's what you do with a, say an infection. We don't think you're crazy."

"No," I said. "Good."

Jack said, "She was talking to me."

I said, "What?"

Rochelle said, "Are you all right, Mark?"

I said, "What?"

"Yeah," Jack said. "Oh, yeah."

Problem Solving

It feels good. It feels right. My radar intercept officer in back hears me howling when we go in. He calls the numbers off, we let the 500s go, and then we're supposed to orbit, wait for the wing leader, go home to Da Nang. But I came in hard on my wing leader's approach. A little close, but still in the classical mode. Maybe I cut it a little steep. I come in, Bird Dog the spotter is asking if I'm hit, my wing man's heading back up toward 4,000 and he's asking, Who's hit?, and I'm howling. Six Phantoms in the squadron had the external pod with the 20 mm gun, they even had ammo that week, and I was in one of them. What I'm saying: it's 1968, I'm a Marine Phantom pilot, I'm strafing a flak installation and it feels good. Turn the selector, look through the display, punch the tit. The ground jumps up around them, then they jump up. They explode, frankly, and sometimes you get to see. That's why I was noisy going in and up and out, and everybody's checking off, checking in, checking up, I level us off at 4,500, stable, and I say, "Goblin on an even keel. Goblin is silky, flight leader."

"Tuck your ass in here and come home," Baseball says.

"Roger from Goblin. Tucking in, heading home. Fuel is not an issue. I have you, Baseball. Here I come."

"Baseball is overjoyed."

But nobody chewed me. I killed some, and that was the job. We interdicted the Ho Chi Minh Trail. We flew out of Da Nang, and every now and again when we went out to bomb the berry people, we blew some up with cannon shells. Now here's what I'm saying: you're up there and I mean homing on them, running right down your own tracers and you're God, you are winged fucking fury, they explode for you like popcorn.

Of course, I'm a reasonable man now, a sane and reasonable man. I sit at a desk that used to belong to a banker. We bought his whole houseful of antiques when I opened the office in what used to be his very Colonial home. I sit at this desk with a top, it rolls down, all these little drawers and compartments are opened out in front of me. This is organized. I write up my notes on the usual legal pad, black ink, yellow paper, green lines, red-ruled margins.

Bomb runs were good. Shooting off the Sparrows was good--take out a prop job the NVA flew, watch those guys break up. The sky looks yellow and green by the time they're down, it's time to go home and debrief, talk the talk. On the way home, the yellow's out of the sky. It has to do with burning aviation fuel, someone told me. So that was good. The napalm runs were good. We had to mix the stuff ourselves, the first few months we were there. Bad-looking stuff, but it did stick to them. It did fry them. So it was good work, and the main thing is: we got to fly. Am I right? We were flying. There's the slip-stream noise coming off the bomb pylons and the gun pod and the radar sticking out of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom, and this was before they rigged the slats on the outer wing, so there's a bit of stick play going on, but nobody's complaining because in the middle of the roar there is a trimmed aircraft and a very well-adjusted, well-trained airplane pilot, and once in a while I got to ride down howling and make popcorn out of people.

Pop pop pop.

If you have a problem, I've always found, you can solve it with a lined yellow legal pad and a good extra-fine point. Draw it up, write it down, lay it out. You work your way in, steady, steady, and you see it. After a while you see it. Tallyho. You say it really low and slow, because you're a Phantom jock, and yours is bigger than theirs. Goblin has the target. He does.

Footwear

You want it new and improved? Goblin offers sneakers, for example. But we approach the issue of the foot by way of, well, what you'd get, sometimes: a rat. You were pretty sure his head would pop partway out of your asshole and swivel around. If the rat takes a look and goes back in, forget about an early springtime. If the rat has no hair, sailor beware. If there's a bald rat chewing out your chest from the inside, popping out be- tween your nipples, then you got a lifetime of less than wonderful luck looking up when you look down. That never happened to me. But I considered how it might. While I was strong enough, and they were letting us use the latrine they made us build, the log on a ditch they told us they might bury us in, I did consider what might climb up and into me.

Also, I thought their shoes would be made of tires from some leftover Renault the French once used. But they were Keds. Old-time, high-cut sneakers. They'd kick your ass around with them, and then they'd line up and piss on you. They would laugh. All I saw was piss like rain, and these all-American canvas shoes on foreign feet. The weather was body temperature, I can tell you.

Which makes it tough. Your kids grow up, and you try and tell them. But how can you tell them why you will not buy them sneakers? Isn't that half of what a daddy does? This daddy doesn't. This daddy can't.

Not Adidas, New Balance, Endicott Johnson Chucky Taylors, Converse with the Velcro strap. So Mickey, my daughter, who is twenty and lives at the other end of the state, in New York City, used to wear loafers, like the kids in the Archie comics. Good girl, Mickey, I want to tell her. She doesn't want to hear it from me. Jack has to wear four different kinds of sneakers because he's a high school jock. Schelle has to buy them, though, along with extra laces. Jack is complaining that somebody took out five long laces from his smelly lost sizes of sneaker. Why would someone need laces? Answer: to tie things with. "I can't do it, Schelle," I tell her. But she knows, of course. She doesn't know exactly what she knows anymore, I think. But she knows. She deals with it. She is a very good woman, and I wish I could have brought home something better for her than a shot-up Phantom pilot with a Navy Cross and carnivorous dreams.

Dr. Micah told her. I was there. It was necessary, she said, for us to see him together. He said, "Old times, they called it shock. Modern days, they said it was battle fatigue, nervous break-down, if you will. New, improved times: post-traumatic stress syndrome."

So Schelle knows its name.

She spent her last teenage years doing what the other college kids were doing: fighting me. Well, fighting the war. Signing petitions. Marching and getting arrested. Jailbait jailbait is what she was. She ends up marrying me. Marrying me.

I have a wife who has worked for three years toward a commemoration of the heroes of the Vietnam War. In our county seat an enormous boulder will be set in the square outside the county courthouse. On a vast polished facing of stone, they will engrave the names of local men who died in the Vietnam War. And I, the lawyer with three-piece suits and European neckties, will stand at the microphone and tell them some stories about the war. She will have arranged it. Schelle. In a world like this, in a world like this, she has worked to celebrate her husband back to health.

To call it irony is to understate the sadness. And no one tells her.

Least of all I.

Closing Arguments

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0449907503

- ISBN-13: 9780449907504