Excerpt

Excerpt

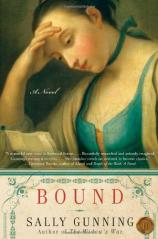

Bound

Chapter One

March 1756

For a time Alice remembered the good and forgot the bad, but after a while she remembered the bad and then had to forget everything to get rid of it; when it came back it came back in bits, like the pieces in a month-old stew --- all the same gray color and smelling like sick, not one thing whole in the entire kettle.

First was the ship. Alice had lived her first seven years of life in London before she got aboard the ship, and if she hadn’t got aboard she imagined she might have remembered better those early years of her life, but the ship and what came after it took away all but a few brown heaps of London ash and dirt. She remembered helping her mother to hang the wash on the fence; she remembered learning to pump the foot wheel to twist fine linen fibers into thread; she remembered constantly sweeping lint and bark and wood chips from under her father’s bootheels as he sat and smoked and talked about the ship.

It seemed to Alice that her father talked about the ship a long time before they ever got on it. Alice’s two older brothers joined in with excited jabber about great stiff sails, sturdy beams, and wide, salted oceans, but Alice watched her mother’s face and stayed quiet. Her mother’s face had clouded at the word ship and stayed so through all her father’s and brothers’ happy clamor; Alice saw the face but didn’t understand it. As her father described it, leaving two rooms full of smoke and damp for a fine house new-made by his own hand in a place called Philadelphia seemed to promise a life as big as the word. But after a time Alice stopped looking at her mother when her father and brothers began their talk of the ship, and when the cart finally came to collect them she was hanging on the windowsill in the same eagerness as her brothers.

Alice’s mother held her tight on her lap through the whole cart ride; when they drew up onto the wharf and saw the ship looming in front of them, Alice’s mother said, “Don’t be afraid, Alice,” but Alice wasn’t. She squirmed out of her mother’s quivering fingers and chased after her brothers up the gangway. The deck of the ship seemed nothing but a large, fenced yard covered with boards, except that it groaned and creaked and swayed back and forth like the pendulum on a clock she had once seen at the magistrate’s.

A man wearing both hat and kerchief on his head led them down a narrow, laddered passage into what he called the “ ’tween decks”; there Alice entertained herself looking at strange faces and listening to strange tongues as her mother hung a curtain around a row of bunks no wider than a set of dough trays. Alice had only just sorted the people around her into families when the tramp of feet overhead grew louder and the creaking and groaning of the ship grew stronger. The deck below her feet began to slant, a little and then a little more, and a collection of cries sprung up around them: “We’re away! We sail!”

A small child wailed. A woman. Another. Alice looked at her mother and saw her eyes brim. Alice returned to her study of the oddly dressed, strangely gabbling people around her and felt herself well entertained until they began losing their stomachs.

Alice’s mother was the first in their family to turn the color of paste and go up to the rail; by the time she returned, half a dozen small children had already washed the ’tween deck with their vomit. Alice’s brothers went next, and last Alice, too sick to notice anything around her; when she returned below, the boards beneath her feet had already turned slick, the air sour and rancid, and the strange families that had amused Alice not long before now seemed too close, too loud, too familiar.

After a time Alice’s mother couldn’t raise herself to climb the companionway to the deck, and Alice, who had stopped getting sick first, was assigned to run up and down with the bucket. Her first trip above in health amazed her. She could look around her now and saw the sails were indeed great and stiff as her brothers had said, the beams indeed sturdy, the ocean indeed wider than anything Alice had ever seen or imagined. The air off the deck felt like a cool, damp hand on Alice’s hot forehead; she breathed it in as far as it would go and held on to it through her return below as long as she was able.

With each trip above Alice noticed that the wind blew harder, which Alice’s father told her was a good thing because it would push them faster to Philadelphia, but Alice thought it good because it built white-topped mountains out of fl at seawater and crashed them on deck in great snow showers. But after a time Alice’s father took the bucket from her and wouldn’t let her go on the deck anymore; she heard him whisper to her mother of a young boy who had been swept overboard, to which Alice’s mother replied, “Lucky boy,” a remark Alice didn’t understand and which her father wouldn’t explain to her.

At last Alice’s mother’s stomach settled, but she began to run as if from a physic, and the brothers too, the stink of their running worse than the stink of the vomit. Alice begged to go out on the deck and cried, which only caused her father to slap her and tell her to go

clean up her brothers, so she gave up crying. By now Alice felt well enough to be quite hungry, but the meat they gave her to eat was so salted that she was in great thirst every minute and the water so black and thick she didn’t like to drink it.

There came a row of days of much the same grayness, where it seemed that everyone but Alice and her father lay sick and moaning, but after a time a few of the men began to raise themselves, and the talk began, at first in a low rumble and then in something louder, with shouting in it. Alice strayed close enough to listen and learned that the wind had come around from the wrong direction, blowing so hard that the captain had ordered the crew to take down sail, which made them drift far off their course for Philadelphia. Some of the men wanted to turn back to London but some didn’t, and Alice’s father finally shouted at them that they might as well stop jawing because the captain wasn’t going to turn around on account of a few days’ short rations. It was true that the salt meat had run out, but Alice didn’t mind because her tongue and lips had begun to blister from it and even though the biscuit they gave her had bugs in it that she had to pick out and snap between her fingers.

Alice’s mother was the first to get fevered; she moaned and called out whenever the waves smashed the ship and knocked her about. One of the men yelled at Alice’s father to shut her up, and Alice’s father hit the man in the face, so other men had to push Alice’s father to the ground until he quieted. The brothers’ fevers came on next, one fast upon the other, but they made no noise at all, which disturbed Alice as much as her mother’s cries.

After a time a surgeon traveling in one of the above cabins came down into the ’tween decks with some bottles of medicine; Alice’s father took out his money pouch and bought a bottle of it; the next day he bought another, but it didn’t help them. The following day he paid the surgeon to bleed Alice’s mother and brothers, but that didn’t help them, either.

Alice’s mother died first. Alice’s father carried her up the companionway, telling Alice to stay with her brothers, but Alice followed her father and watched from the hatchway as a sailor with a missing finger and one with a broken tooth took her mother out of her father’s arms and threw her overboard into the water.

After that Alice’s father grew quiet; Alice had to tell him when her brothers died, near together, two days after. Alice watched them go over the side too, imagining her mother catching them and calling them lucky boys as she’d called the boy who’d been swept overboard near the start of the voyage.

Another long, gray period dropped down until a morning when a great disturbance woke her from sleep; she opened her eyes to see people sick and well laughing and shouting and pushing for the companionway. “’Tis land!” “Land sighted!”

Alice and her father went up on deck with all the others; after a time Alice saw a fl at, brown crescent dotted with low hills and a smattering of little steeples, but everyone cried with joy at the sight of it, except her father, who cried but did not look joyful in it. Alice

didn’t feel like crying, but neither did she feel joyful, so she stood silent and clung to the rail, peering over at what she had thought was Philadelphia but soon learned was someplace else called Boston.

The ship sailed past many little islands into the harbor, toward the brown crescent, which Alice could now see was rimmed by buildings, little dots of things, nothing like the walls of brick and stone that framed the river at London. A smaller boat rowed out to meet them, and the ship was towed until it could be tied up snug against a long wharf that stuck out deep into the water. The captain shouted the sailors into lines to fold the sails while Alice busied herself watching the carts and carriages and people moving along the wharf, trying to find out if these people were different from the ones in London.

After a time Alice’s father took her hand and led her back to the companionway. Down below, one of the ship’s men walked among the passengers too sick to go on deck and wrote things in a log; quite often someone would shout weakly at him but he never shouted back, only answering in a fl at voice before moving to the next person. Alice’s father stood for some time in silence, watching the man, and then dropped Alice’s hand. “I must go talk with that fellow. Put our things together, Alice.”

Alice changed her dirty shift for one that was a little cleaner; she put on the least worn of her two dresses and packed the other things in the trunk on top of her mother’s shoes and stockings and shawl, which her father had removed before he’d seen her into the water. She added the pair of pewter mugs and plates, the three blankets, her father’s tobacco pouch, and some papers he’d been looking at before land had been sighted. She watched her father as he talked to the man; she could hear her father’s voice well enough, but not the man’s quiet answers. She moved closer.

“Like I told you,” the man said. “Dead after half the voyage still

means full fare.”

“The girl’s but seven.”

“Seven’s still half fare.”

“Then I’d like you to tell me what surgeon charges ten shillings for a bloody bottle of piss and a bleeding I’d have done better with a marlin spike!”

“That you take up with the surgeon.”

The man walked off. Alice’s father returned to Alice. He looked at the air above her a long time, but after a time he drew his eyes down and took her in from top to bottom, as if he weren’t sure howshe’d happened to come along on the ship with him. He said, “Wash your face. Comb your hair. Brush up that dress and stay here till I collect

you.” He disappeared up the companionway.

Alice did as her father said; as she waited for him to return she looked around and noticed others doing much as her father had told her to do. A mother spit on the corner of her skirt and rubbed her wasted children’s faces; a near-grown girl yanked a comb through a smaller girl’s hair; a girl Alice’s age picked at a crust on the seat of her brother’s breeches.

Alice’s father came back and kicked the trunk. Alice remembered that --- he kicked the trunk --- but she couldn’t remember that he said any words to her. Later she thought there were some words she’d forgotten; later again she thought there were no words what ever. He took her hand, led her up on deck to a line of worn-down, bleachedout passengers, and pushed her onto the end of it. After a time a stream of finely dressed men and ladies walked up the gangway and down the line of passengers, looking them over with what seemed to Alice an odd amount of interest. One lady stopped at Alice and felt her arm. A gentleman told her to open her mouth. Another lifted her skirt. One man with a locked knee asked Alice’s age and then moved off, so Alice didn’t think of him any more than another, but after a time he came back and asked if Alice’s father was her father, and when her father said he was, the man asked him a lot of questions, which Alice’s father answered in a high, tight voice Alice hadn’t heard in him before. She’s the healthiest on the whole ship, as you can see for yourself, sir. She’s quick and she’s good behaved, and she can spin and use a tape loom, if someone sets the web for her. She’ll not give you a sorry day, I promise you that, sir.

The man with the locked knee waved Alice’s father out of the line, and they disappeared into the after cabin. When they returned, Alice’s father had a paper in his hand, which he folded and pushed into his money pouch. He tied the pouch around Alice’s neck. “You’re to live with Mr. Morton now. Do as he tells you. Remember God. And keep hold of that paper.”

Mr. Morton took Alice’s hand and led her to the gangway. “Grab onto the rope, child. Watch your feet.” Alice grabbed onto the rope and watched her feet, but once she landed on the dock she twisted around, looking for her father. Mr. Morton pulled her along, but she continued to twist, looking over the feeble string of passengers stumbling onto the wharf, not finding her father in them. Mr. Morton led her to a dusty carriage and boosted her into the seat; from there Alice had a better view and after a time she spied her father pushing their trunk into the back of a rough wagon. He climbed in after the trunk; three other men Alice recognized from the ship climbed in after him; the wagon clattered into the road heading into the sun so that the wagon and the men became nothing but a sharp black lump against the sky. Mr. Morton moved his carriage into the road and moved off with the sun behind him.

Bound

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0061240265

- ISBN-13: 9780061240263