Excerpt

Excerpt

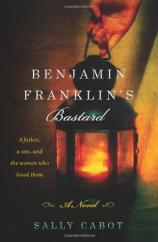

Benjamin Franklin's Bastard

Chapter 1

Philadelphia, 1723

IT WAS ONE OF those days that struck the fifteen-year-old Deborah Read from time to time—she could work away most mornings without complaint, through heat or cold or even spinning flax, the worst kind of domestic tedium—but then an itch would come up in her and she couldn’t bear to be inside at her work a single minute longer. She’d been scrubbing a hearth spill and had gone to the door with the bucket of dirty water, intent on dashing it into the gutter and returning to her task, but the sights and sounds and smells of the street grabbed hold of her. Most of what she saw was the usual drab Quaker gray, but of late Philadelphia had added other colors and tongues: Irish, German, Scots, free Africans, all come to see if it was true—this Quaker promise of peaceable commingling of all peoples and beliefs.

Perhaps it was. Deborah looked along Market Street and saw Brock Mueller teasing his oxen along in his usual off-note singsong; farther on, past the bakery, John McKay was just sweeping his stoop. Opposite the courthouse, two small Quaker boys chased a loose pig grubbing in the mud for whatever it was loose pigs always grubbed in the mud for, and in the other direction, toward the river, an old Negro woman sat on a crate under the covered market, empty on the off day, rolling a stone between her palms and muttering to herself. Deborah’s gaze was about to travel past the old woman to the waterfront and the ever-present masts poking against the sky when she saw someone coming down the street in her direction, a stranger not much older than herself but already tall and broad backed, with a strong, lively face. His clothes showed the dust of travel, and leaking out of his pockets she spied what looked to be all his worldly goods—a dirty shirt and a pair of stockings. He strode along chewing on a roll while carrying two others beneath his arm, as if determined to keep a full day’s ration on tap. Later she would tell this story of her first glimpse of the great Benjamin Franklin—how she, Deborah Read, stood in the doorway of her father’s house on Market Street, looked at this comely young man walking by with his laundry and his rolls, and dismissed him as beneath her notice. But when telling the tale Deborah always took care to tell the whole of it—that the man had bent down and offered one of his rolls to the old Negro, as if to prove he wasn’t in as great a need of it as he looked.

WHEN DEBORAH NEXT SAW Franklin, he was standing on her father’s stoop asking after a room to let. The rolls and dirty clothes were gone, and he was claiming a fair wage as assistant in a printer’s shop; the day was hot and Deborah had been walking around limp as a dishrag, but when the stranger appeared on the stoop she felt herself taking in a little starch.

Franklin peered around the father to examine the daughter. “I remember you,” he said. “Standing in the doorway with your dirty wash water.”

Deborah opened her mouth to snap back something about Franklin’s dirty linen, but she took note of a look in Franklin’s eye that told her he expected her to do it, that he’d laid out the dirty wash water just so she’d have a chance to lay out the dirty linen, that he was proud of how far and how fast he’d come and wanted her father to know it. Deborah stayed silent.

DEBORAH’S FATHER LET FRANKLIN the room, but at first Deborah hardly noticed—it seemed Franklin had already made a lot of friends, and he met nearly nightly with them at one or another tavern—but after a time he began to appear at the kitchen table or the family fire as if he’d always been part of it. From that point onward, life in the Read home changed. One morning Deborah came in from hanging the wash to find Franklin at the table, filling glasses with different amounts of water from a jug. He caught Deborah’s hand as she walked by, spread her fingers apart, dipped her forefinger in the water, and guided it to the rim of the glass, moving it around and around. Then the glass began to vibrate, the finger to tingle, the glass to let out a sound like a cat fallen into a molasses barrel. Franklin added water to the glass; Deborah tried to pull her hand away, but Franklin held tight to it. He rimmed the glass with her finger again, and she noticed the sound had mellowed. He let go of her finger and took up a glass of his own, adding and subtracting water until he’d made a new note. When Deborah’s mother came in from the shops, they’d created eight separate sounds, dried out the roast, and scorched the newly washed napkins hanging by the fire for drying. Benjamin took the blame—and the credit—for the whole of it.

THEY ALL LIKED IT when Franklin was around—Deborah’s father and mother and Deborah—but Deborah suspected she was the only one who listened for his step on the stairs. She took care not to show Franklin any special attention and felt she did a fair job of it, but after a time it seemed clear that Franklin was showing her some special attention. He met her out at the well and carried in the bucket, he noticed when she tied back her hair with a new ribbon, he sat up with her while she did her sewing after the rest of the family had gone to bed. On those nights alone together he told her about Boston, the town where he was born, how it was laid out over old, winding cow paths, so unlike the neat grids of Philadelphia. He talked too of a wind-racked island called Nantucket, where his mother was born, and how his grandfather had bought his grandmother out of indentured servitude to marry her. And one night he told her his astounding secret—that he was a runaway indentured servant himself. If Deborah’s father had known, he would certainly have warned Deborah away from the man, perhaps even evicted him from the house, but the problem was simply enough solved; Deborah told her father nothing of it. Already, she didn’t like to think of a day without this man’s attentions in it.

Another night Franklin came in with news that Deborah was glad enough to share with her parents—Franklin had met the governor! The governor had by chance seen a letter Franklin had written and had been so impressed with it that he’d requested a meeting. At the meeting the governor suggested that Franklin set up his own print shop in Philadelphia—when Deborah told her father this news, she looked to him in the hope of an offer to assist the young printer, but no such offer came. Afterward Deborah wished she’d looked harder at her father, or talked longer, or made him his favorite custard for dinner; in the morning she found him dead in the yard, halfway between the house and the necessary.

DEBORAH’S MOTHER TOOK CHARGE of the lease of the carpentry shop and paying off the creditors, but it was Franklin who kept them afloat above the waves of grief that pounded them from all sides. He made sure to spend time in gentle chat with her mother, but it was Deborah who was clearly his main concern; he began each morning with just enough words to warm her and ended each night by walking her up the stairs to her chamber, always saying a proper good evening at the threshold. At first Deborah only thought of how nice it was not to have to walk past her parents’ chamber door alone, not to have to think of her mother lying in there beside an empty bolster. But after a time Deborah’s thoughts began to veer away from the dead to the living, to the tall, solid form that accompanied her. She began to feel queer things when he happened to brush against her thigh or when his hand rested low on her back, just above the curve of her buttocks, to guide her up the steep stairs.

One night Deborah opened her chamber door and discovered she’d left her window open in the rain. Franklin stepped into the room to wrestle with the sash, but he wouldn’t close it all the way down.

“Fresh air is healthful,” he said. “No one catches cold from cold; in fact, a close, overheated room is the more likely culprit.” He went on about the healthfulness of certain airs, and Deborah pretended to listen, but she only really caught up again when he crossed to the bed and began to admire the embroidery on her coverlet.

“I wonder if you know how often I think of that coverlet and the treasure that lies beneath it,” he said.

Some number of nights later—it was not that same night, Deborah was almost sure of it—she found herself lying under that coverlet with Franklin, discovering all the things that could happen to a woman unaware, as long as a man went about it politely enough.

BENJAMIN WAS ON THE RISE—Deborah could feel it—even before he clattered his way up the stairs and into her room one night way too loudly, almost shouting: The governor had offered to send him to London with letters of credit to purchase the press and types needed to set up his own print shop in Philadelphia!

It was exciting news, no doubt of it, but Deborah couldn’t help it. Her father was dead and her mother only just afloat on the shop rent; Deborah had gone too far, and all that could save her if trouble came was this man who was about to leave her behind on a distant continent. A thick, dark, panicked grief dropped over her, stopping her tongue.

“Well?” Benjamin asked. “Don’t you have something to say of your fine fellow?”

“Are you?” she asked. “Are you my fellow?”

He heard. He knew. He took her hand and pulled it tight to him. “We’ll marry before I go,” he said.

The cloud over Deborah lifted. She would have married Benjamin Franklin no matter what he was, but marriage to Benjamin Franklin, print shop owner, could be all her father would have wanted of her.

When they spoke to Deborah’s mother, however, she didn’t see any print shop owner—she saw only an eighteen-year-old printer’s assistant and a sixteen-year-old, restless daughter; whatever her affection for the man, it would not allow of any financial risk for her daughter. Or so she explained it to the pair of them.

“Go to London, Benjamin,” she said. “Come home. Set up your shop. Then talk to me of marrying my daughter.”

Deborah considered telling her mother what she’d already risked with Benjamin, but she wavered, thinking of the disgraced Sue Kent’s exile to relatives in Virginia, her mother’s firm endorsement of the parents’ actions in the matter. In the end, Deborah decided she didn’t trust her mother as much as she trusted Benjamin.

Chapter 2

DEBORAH WOKE IN THE old anticipation that lasted only as long as it took her to come fully awake and realize that the day would have no Benjamin in it; she’d guarded herself against total despondence over Benjamin’s leaving—she would not erase herself from life in his absence—but she hadn’t been prepared for the blandness that was left. To pull herself up she fixed her sights on Benjamin’s first letter, practicing in her mind her possible answers to it. She was not skilled with words and anticipated much to live up to from a man who made his living at them; if he wrote in long sentences of all the fine carriages in the London streets, she must counter with something of equal interest, if not with equal skill. But what? Deborah’s days were full of the things they’d always been full of: spinning, washing, sewing, cleaning, the Wednesday trip to the covered market that ran two full blocks down the middle of Market Street, the Sunday trip to the butcher’s shambles for a fresh leg of mutton or a haunch of beef. It had been enough; she’d always put her best effort into her chores, proud of a full skein and a clean house and a good meal, but she couldn’t imagine writing of such things in a way that would make them interesting to Benjamin.

So Deborah went, marking the days in her head—the four to six weeks that he would be aboard ship wouldn’t hold promise of a letter unless they crossed with a homebound ship and hauled up to exchange mail sacks. Four weeks came and at the end of it Deborah reminded herself of how foolish she’d been to hope of such an exchange at sea; at the six-week mark she reminded herself that a six-week voyage was a good voyage—there were many bad voyages that went on into months. At the two-month mark Deborah reminded herself that even once in London, Benjamin would still have to wait for a return ship to deliver the letter he would of course sit down at once to write.

At the four-month mark Deborah’s mother began to say things that Deborah took as ominous. “Young and vigorous men do not always possess vigorous memories,” she said, or, “That potter, John Rogers, seems to be making a good living out of his shop.”

After six months a letter came. It made no mention of a prolonged voyage, or an illness, or any other inconvenience that would have explained the delay. He wrote of the governor’s letters of credit proving worthless, of finding employment at a quality printer’s, of the vastly greater opportunities London offered over Philadelphia; between those lines lay the only explanation Deborah was to receive of the last one: “I am unlikely to return to Philadelphia anytime soon.”

Deborah answered the letter, taking great pains over it, but in reading it back she saw clearly enough that it didn’t even measure up to Benjamin’s disappointing offering—she sensed that the words didn’t look right, but they gave no hint as to how they could be bettered. She almost didn’t put the letter out for the post, but she knew how she’d felt in all those months of waiting. In the end she decided that a poor letter was better than none and mailed it anyway. After six long months with no answer she mailed another. She didn’t write again, but she couldn’t say that she didn’t continue to wait. It wasn’t that she believed Benjamin would come back or that he would even write again, it was more that she wasn’t able to erase him as easily as he’d erased himself. She’d long envisioned what her future life would be like, and it varied little from her mother’s: a modest but well-kept tradesman’s house, a full pantry, a warm hearth, and every other year an infant in a cradle beside it. Since he’d first slipped himself under Deborah’s coverlet, the man she’d pictured on the other side of that hearth had been Benjamin Franklin, and she couldn’t seem to move him out of that seat.

DEBORAH’S MOTHER HAD NO such trouble moving Benjamin; she kept up her talk of John Rogers’s agreeable nature, his mastery of his trade, his interest in Deborah. “What more are you after?” she asked.

Musical glasses, Deborah thought. Astounding secrets. Lectures about healthful and nonhealthful airs—although in truth Deborah didn’t miss the lectures so much. But as Deborah’s mother said, John Rogers was there, and Benjamin Franklin was not.

John Rogers was invited to dine; Deborah’s mother set out to make him feel welcome and did so; John Rogers set out to make himself welcome, and he did that. He used the visit to good purpose, making a fair account of himself to Deborah’s mother—not long arrived from London, he was already making forty pounds a year out of his shop. He made no pressing demands for speech from Deborah but included her in his talk with the mother with the kind of look that expressed well enough his intent. In fact, he seemed unwilling to take his eyes away from her face and form, and Deborah could not help but feel the compliment in it.

As the night wore down, Deborah’s mother made an excuse to retreat to the kitchen, and Rogers proved himself the gentleman by asking Deborah’s leave to call upon her again; once it was granted he stood up and bid her good night.

John Rogers called five times before declaring his desire to make Deborah his wife. She’d by then learned he was proper and pleasant and attractive enough in his person, although he had a habit of licking his hair behind his ears that she didn’t like, but it seemed a small enough fault. Still, Deborah answered Rogers, “I’m not of a mind to marry yet.”

When Deborah’s mother heard of her answer, she said, “Very well, there’s an advertisement in the newspaper for someone to scrape skins at the hatter’s shop.”

When Deborah’s eye widened she said, “I can’t afford to keep you. ’Tis one thing or the other—you go to wife or you go to work.”

That night Deborah lay in bed with her eyes tightly closed and tried to reimagine her old hearth, the cradle at one side, the chair at the other, but with Rogers sitting in it instead of Franklin. The room seemed dim and cold, the fire weak, with Rogers little more than a dull gray shape; but when she tried a second trick, putting her mother into that chair, the room grew too close and overhot. And what of an empty chair? The minute she tried to picture it the scene went black.

John Rogers returned. Deborah never did know if her mother had summoned him or if he’d come of his own accord, confident enough that he’d not be turned away twice. Deborah’s mother left them alone in the parlor, and John Rogers stood before her and spoke in his most earnest voice. “My disappointment at our last meeting was great. But here I am again, in hopes that perhaps you’ve had a second thought.”

“Perhaps if we talked of it again in a year—,” Deborah began, but John Rogers shook his head.

“I’m not so young as to have a year to waste.”

“But my daughter is.” Deborah’s mother had come through the door. “She’s young and unused to the idea as yet. Surely another month or two could be allowed her.”

“I could not object to a month.”

The talk went back and forth, Deborah saying little, until belatedly she realized just what it was they talked of—not a renewed suit in a month but a marriage in a month. Deborah leaped up from her chair to correct the plan while she could, but her mother turned on her such a bright smile of satisfaction that Deborah could see in it the clearest reflection of the reverse—the face she would be staring at across her mother’s hearth if she chose to remain at it single yet. She also saw the hatter’s shop. She turned from her mother’s smile to Rogers and saw that he waited on her word, understanding that nothing could be settled until she said it herself; Deborah’s mother talked on, and still John Rogers watched her and waited. Perhaps after all it was not such a poor prospect, life with a man who would grant her her own mind? Indeed, if she kept Benjamin Franklin out of it, this man would measure up well against the rest, and, as her mother repeated again and again, Benjamin Franklin was indeed out of it.

“A month,” she said.

DEBORAH’S MOTHER AGREED TO a dowry she could ill afford, culled out of the sale of the remaining inventory at her husband’s carpentry shop. Deborah’s mother offered no money for wedding attire, but Deborah didn’t object—she’d already discovered the sum of her assets lay in a full figure and a fresh face that would show up just as well in her unadorned lavender bombazine and navy cloak. The justice of the peace said the necessary words over them in the parlor, and Deborah’s mother made a roast of the last of the freshly slaughtered pork. After he’d cleaned two plates, John Rogers stood up, swiped his hair behind his ears, said his thank you to Deborah’s mother, and pointed Deborah to his cart. He hoisted her trunk in after her and geed his horse into the street; Deborah turned to say a last word to her mother, but the night was cold and her mother had already gone back inside the house. Looking at the door of the place where Deborah had lived the whole of her life, she began to think that perhaps she’d given up a known thing for an unknown thing without sufficient thought, but it was, as her mother would certainly have told her if she’d voiced the idea out loud, too late.

Rogers’s house was on Warren Street, at the far end of Market, the houses growing smaller and darker as they progressed. Rogers spoke little on the short ride and made no grand announcement of any kind as they entered. Deborah didn’t particularly mind, as she’d occupied herself with her own thoughts, or perhaps better said, with one particular thought: Would Rogers be able to tell that another had already explored parts of her he might well expect to explore first? A memory of her last time between the sheets with Benjamin caused her to flush with double shame—at the act itself, and at thinking of Benjamin Franklin hours after she’d wed someone else.

Rogers handed her down at the door, raked the trunk across the threshold, grinned at Deborah, and pulled her up the stairs. Two closed doors greeted her at the landing and Rogers opened one of them, unleashing a cold, damp draft. Deborah would have liked a few more words with her new husband, or better yet, a cup of tea, but neither was offered, and Deborah, feeling herself already in the wrong, made no fuss.

It turned out not to matter. There was, Deborah discovered, a not-polite way to bed a woman, and if Rogers noticed any lack in her it didn’t slow him. He fell asleep, woke and kneed her legs apart again, drained himself, slept again. Deborah now saw the great advantage of remaining chaste till marriage—the night would have been a good deal less disappointing if she’d had no comparison to make.

The second disappointment was her new husband’s empty pantry. Deborah managed their breakfast out of toast from an old crust of bread and the dregs of beer from the beer barrel; she offered them up to Rogers with what from her mother would have sounded like apology but from her came out as accusation: “Your pantry needs stocking.”

“Gray’s has my account,” Rogers said, the only words he’d spoken to her since she’d arrived at his house. He swiped his hair behind his ears again and left for his shop.

LIVING WITH ROGERS PROVED to be little different from living alone, and alone, Deborah turned to her thoughts. That her thoughts were too often of Benjamin Franklin she knew to be wrong, but she didn’t care. Her thoughts, at least, were hers, and she’d do with them as she liked. The first sign of deeper trouble came a month into her marriage when Deborah put a sack of Indian meal on the counter at Gray’s and was told that John Rogers no longer had an account. Deborah told Rogers that night.

“I’ll square it,” he said, and went out.

That night Deborah learned another new thing—that there was something besides Benjamin Franklin’s good nature that could be brought home from a tavern—but when she went to Gray’s the next day there was no trouble over the account; it was another month before she discovered from Gray’s store that all her purchases were now being charged against her mother’s account. Deborah returned home, went straight to her husband’s desk, and prized it open without compunction, hunting out his ledger book. Deborah was not good with words, but she was good with numbers, having helped her father from time to time in his shop, and she could soon track the spending of the entire dowry she’d brought with her to her marriage, as well as the long list of remaining debts. She closed up the desk and sat long in thought. As affairs now stood, the only advantage to her marriage to John Rogers went all to John Rogers, with her mother forced to keep the pair of them at her own expense. Deborah thought longer, and could see only one way to improve her state as well as her mother’s: She climbed the stairs, packed her trunk, and wrestled it back down the stairs with greater ease than she’d wrestled it up. She found a cart boy at the corner and gave him a coin to take it and her to her mother’s house.

Her mother heard the racket and came out into the hall. “What in heaven is this?”

“We’re done with Rogers,” Deborah said, “and you’d do well to inform Gray before he takes all you own to pay off the man’s debts.”

“What!”

Deborah explained. And explained again. Her mother was the sort who had her own idea of a thing and didn’t like to give it up; in the end she went out to Gray’s and came back the color of sour milk, apparently drained of ideas altogether.

“What are we to do? You still bear his name.”

“He may keep his name,” Deborah said. She climbed the stairs to her old room, opened the window, and breathed in the cold, healthful air.

SOON AFTER DEBORAH’S FLIGHT John Rogers disappeared, and in time the rumors began to fly around Market Street from every point on the compass. John Rogers had a wife in London. John Rogers had fled to the West Indian Islands to escape his creditors and had taken a third wife. John Rogers was dead, beaten to a pile of bones by one of his creditors. Or the third wife. At first Deborah didn’t care where he was or whom he was with or, indeed, whether he was alive or dead— her earlier rage had washed away under a crashing wave of relief—but after a time Deborah realized that what had happened to her husband had to matter to her. If she had no proof of his death, if she had no proof of that London marriage, Deborah was herself as near dead as any living woman could get. She had no husband, but neither was she free to marry another unless she could afford to legally investigate either the first wife in London or the possible death in the West Indies. The dowry for Rogers had taken all that the Reads owned in the way of assets. Any legal fees were as beyond Deborah’s grasp as the tops of the masts that lined the Delaware River.

DEBORAH’S MOTHER BEGAN TO have difficulty on the stairs, and with the washing, and with balancing over the fire to lift the skillet; she began to tremble as she worked her needle. Deborah took on the main of the chores, settling her mother in her chair with some wool to wind or some dough to knead; at night she helped her to bed and returned below stairs to sit alone with her sewing. The relief that had washed away her anger over John Rogers was in turn washed away by a hopelessness that had heretofore been entirely alien to her nature. She got out of her bed and did her chores and her nursing but didn’t go out beyond what was needed; she could see the looks on the faces she passed, as if she were lame or disfigured. Nothing moved her until one day on her way back from her errands her eye happened to fix on the masts dissecting the sky.

Deborah walked toward the water. From a distance the river looked still, but as she drew closer she saw how fiercely it ripped into its bank, that she was the thing that was still. She wondered what happened when a still thing hit a moving thing, where the still thing might end up. Benjamin would have known; Benjamin was a strong swimmer, had even experimented with paddles on his hands and feet to make him an even stronger one. He’d once hitched himself to a kite and let it drag him across the pond, testing the power of the wind against a few sticks and pieces of paper.

“But how did you get back?” Deborah had asked.

“Paid a friend sixpence to carry my clothes around the pond and walked.” Benjamin chatted on about this and that amazing thing he’d discovered about wind and water as he blew across the pond, but Deborah only wondered that as he’d walked home wet and cold and short an entire sixpence it hadn’t occurred to him how foolish it was.

THERE MUST HAVE BEEN a dozen ships lined up along the river, but every one sat with sails furled, as stagnant as Deborah, having long since discharged its passengers and cargo—if Benjamin Franklin had been aboard any one of them he certainly hadn’t come looking for her. Deborah stared down at the angry current again, so dark and rough she couldn’t see bottom, and shuddered. She should go home— her mother grew nervous when Deborah left her alone too long—but she felt too old and achy and worn out to even make the turn against the wind. She was seventeen and finished.