Excerpt

Excerpt

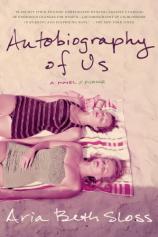

Autobiography of Us

Chapter One

She died before her time. Isn’t that what people say? Her namewas Alex—Alexandra, though only our mothers and teachers ever called her that. Alexandra was the wrong name entirely for a girl like her, a name for the kind of girl who crossed her t’s and dotted her i’s, who said God bless when you sneezed. From the day she arrived at Windridge, we were the best of friends. You know howgirls are at that age. We found each other like two animals recognizinga similar species: noses raised, sniffing, alert.

Funny, isn’t it? To think I was once young enough to have a friend like that. There were years she meant more to me than anyone,years our lives braided into each other’s so neatly I’m not sure, to be honest, they ever came undone. Though how does one even track such things? Like the movements of the moon across the sky, she exerted a strange and mysterious pull. Even now, I could no more chart her influence than I could the gravitational powers that rule the tides. I suppose that could be said of anyone we love, that their effects on our lives run so deeply, with such grave force, we hardly know what they mean until they are gone.

I was fourteen the day she appeared in my homeroom. A transplant from Texas, our teacher announced, her hand on Alex’s shoulder as though she needed protecting, though it was clear from the start Alex didn’t need anything of the sort. She must have come straight to our classroom from home that day, because she wasn’t in uniform yet. Instead of the pleated navy skirts and regulation white blouses we had all worn since the third grade, she had on a red flowered dress with smocking across the front, ruffled at the neck in away my mother never would have allowed. I remember being struck right away by how pretty she was—unfairly pretty, I thought. In those days I was a great believer in the injustice of beauty, and I saw immediately that Alex had been given everything I had not. She was thin through the arms and slender rather than skinny, with a pale, inquisitive face that might have seemed severe if it hadn’t been for the franks nubness of her nose and the freckles that stood out against her cheeks. Her dark hair she wore loose around her shoulders, her eyes startling even at a distance, the color a deep, sea-colored green, the right slightly larger than the left. Released to her desk, she chose the route that took her directly past mine—accident, I thought, until she turned her head a quarter inch and winked.

I was as blind as anyone as to why she picked me. I had by that age already established myself as a shy girl, bookish, and in the habit of taking everything too seriously. Of the fifteen girls in ourhomeroom that year, Ruthie Filbright was the prettiest, Betsy Bromwell the nicest, and Lindsey Patterson the biggest flirt. But it was me Alex winked at that September morning, me she approached at tennis that same afternoon. Me she rolled those eyes at when Lindsey flounced past, twirling her racket; me she flung herself down next to on the bench, kicking her legs out in front of her, her shins scabbed in a way I was aware I should have found ugly but did not. What I saw was that her shoes were covered with some sort of embroidered silk, that her fingernails were painted a shocking pink—the shade, I would later learn, Cyclamen. That she was, depressingly, even prettier than I had thought.

“Boo,” she said, frowning at a splotch of ink on her wrist. She rubbed it with her thumb, then brought her wrist to her mouth and licked it.

“Boo yourself.” I felt my cheeks heat right away.

But she was busy looking around, her expression caught somewhere between amusement and boredom. “Don’t tell me,” she said.

It was a thrilling voice, surprisingly deep for a girl her size.

“They’re every bit as bad as they look.”

“They’re nice enough.”

She crossed her arms over her thin chest. “And you? Are you nice?”

“That depends,” I said slowly. “There are different kinds of nice.”

She smiled. Her mouth was the one real oddity in her face: It was too large, too wide, the upper lip full in a way that erased the usual dip in the middle. Still, it was a surprisingly sweet smile. “So you are different.”

I didn’t need to look up to know everyone was watching—Ruthie and Lindsey and neat-faced Robin Pringle. I could feel their eyes, those girls standing clustered close to the fence, pretending to bounce tennis balls or check the strings on their rackets while they watched the new girl drag the toes of her ivory shoes carelessly back and forth in the dust. And they were watching me, Rebecca Madden, who until this very moment had been just another quiet girl in the corner, easily passed over and as easily forgotten.

“I don’t know,” I said finally. “I guess I’m more or less like everyone else.”

She brought her head down close to mine then, so close I could smell the sharp floral scent of what she would later inform me was her mother’s perfume—filched, she would say, from her dressingtable and applied liberally to her own wrists. “Now, if that were true,” she said softly, “what in the world would I be doing over here?”

She lived, we discovered after school that day, just three blocks down on El Molino, in a beautiful old Tudor surrounded by bougainvillea and a high wall that ran around the perimeter of the property.

“Hideous, all of it,” she announced as we walked. “You’ll see. Eleanor’s had the place done Oriental—oh, I don’t care for honorifics. It’s Eleanor and Beau around here, and they’ll expect you to call them the same. Anyway, the whole thing’s silk and tasseled pillows and these awful little Chinaman figurines, which she insists positively ooze the West Coast esthétique. Meanwhile, I only know everything about California there is to know. It might have behoovedher to ask my opinion.” She gave me a sidelong glance. “Aren’t you going to ask how I know everything about California?”

I straightened up. “How do you know—”

“I’m going to be an actress. Isn’t it obvious? I know what you’re thinking,” she added quickly. “But I’m not talking about the pictures. I mean the serious stuff, the Clytemnestras, the Heddas.

Shaw, Brecht, et cetera. None of this fluff. It used to be about talent, you know. Look at Marlene Dietrich, for Christ’s sake. No—wait. ”She shut her eyes. “Don’t tell me. You don’t have a clue.” She blinked at me. “Poor thing. Never mind—I’ll have you out of the Dark Ages in a jiffy. As for la Marlene,” she went on, “there’s no doing her justice with words. You’ve got to see her to understand. She came through Houston on a tour last fall—this awful cabaret thingy, really juvenile stuff, but, I swear, I would have sat in the audience and watched her slice bread. I mean, I could have sat there in my goddamn seat forever.” She put her hand on my arm. “Have you ever had one of those moments?”

“Which kind?”

She looked at me intently. “The kind where you feel like everyone could go to hell. Like you wouldn’t care if the whole world blew to pieces.”

I pretended to think. “I’m not sure.”

“Then you haven’t found it.”

“Found what?”

“Your something,” she said, impatient. “Your heart’s desire.”

“You’re saying yours is acting.”

“Listen, I’m not exactly thrilled about it either. I would have preferred something with a little more”—she clicked her tongue—“gravitas. That’s the thing about callings—they choose you.”

“But how do you know?”

“That’s like asking how anyone knows to breathe.” She’d stopped walking now, her hand still on my arm. We were standing under the shade of one of the big palm trees that lined that stretch of El Molino, and in the late-afternoon stillness I heard the drone of a honeybee circling overhead. “Look, I wasn’t given this voice for no reason. I’m not saying it to brag. I’d a thousand times rather have been given just about anything—a photographic memory or the ability to speak a dozen languages. Something useful. But I’m stuck with what I’ve got. Not to mention what I haven’t. Schoolwork, for starters,” she went on. “Oh, some of it I do alright with. Reading, for one. I happen to be a voracious reader. You?”

“I like to read,” I began. “I—”

“I’m perfectly tragic when it comes to arithmetic,” she went on.

“And teachers are always telling me I’ve got to improve my penmanship. Frankly, I have neither the time nor the inclination.”

She looked at me. “I bet you’re the type whose papers get held up in front of the class. I bet your goddamn penmanship gets topmarks.”

I shrugged. “I do alright.”

“Because you’re a realist. Don’t look like that—it’s a compliment. Anybody with the slightest smidge of intelligence is a realist. The point is that you get the appalling fact of the matter—that we’re alone. Doomed to lives of quiet desperation or what ever. Thoreau. ”She squinted at me. “You do know Thoreau.”

“Of course I do.” I pleated the material of my skirt between mythumb and index finger, eigning concentration to cover the flush I felt moving up my neck. I am, as you know, a terrible liar.

“Listen to me.” She gave me a dazzling smile. “If we’re going to be friends, you’ll have to learn to ignore me when I get like this. I goon tears, that’s all. There are things better kept to myself, Eleanor says. Problem is, I’m an only—child, I mean. Afraid I don’t always remember to think before I speak. Sometimes things come out without”—she chewed on her bottom lip—“arbitration.”

“I’m an only, too.”

“Were there others?”

“Other what?”

She gave me a penetrating look. “Eleanor had three before me. Or two before and one after, I can never keep it straight. You know—dead ones. Was it the same with yours?”

“I don’t think so.” I felt myself frowning and tried to relax my forehead—Mother telling me I looked pretty when I smiled, that frowning never did anyone’s face any good. “My mother traveled before she had me. Turning pages for a famous pianist.”

“You’re kidding.” She stared. “And now what?”

“And now what, what?”

We started walking again. “What happened to her and the pianist?”

“She got married, silly,” I said, laughing. I’d always found the story romantic, though I had a feeling if I admitted that, Alex would only shake her head or roll those startling eyes. “She and my father met in a restaurant. She was out with Henry Girard—the pianist—after a concert one night. Daddy had just come back from the war. ”I tried to make it sound as though I could hardly remember, though of course I’d memorized every detail: my mother at a table with the famous pianist, her blonde head gleaming under the chandelier; my father in the corner with his wounded leg stretched out in front of him; across from him, his date, a woman whose face—no matter how many times I tried to picture it—remained blank. My mother young and beautiful in a green dress; Henry Girard aging, brilliant, bending his gray head over his soup. My father waiting until his date excused herself to the ladies’ room to stand and walk over to where my mother sat—a face like that, he said, impossible to ignore. “They got married not long after.”

“Sounds exciting.”

“It was,” I said, glancing at her, but she only looked thoughtful.

“She always says he swept her off her feet. She says he—”

“I meant the working with the famous pianist bit.”

I shrugged. “She doesn’t talk about it much.”

“Like the dead babies.”

“Not exactly like that.”

“I think I would have liked one,” she went on, ignoring me. “A sister, anyway. I’m fine without the brother. I never would have known, obviously, except my parents get in these god-awful fights. Beau was saying something about family once, taking responsibility,and Eleanor just shrieked at him, If you blame the dead ones on me one more time, I swear—” She stopped. “The dead ones. Ghoulish, isn’t it?”

“Maybe a little.”

“I’m headed toward something sanguine, in case you were wondering.” She looked at me pointedly. “From the Latin sanguineus, meaning bloody. Hopeful. Optimistic. Point being, I believe we’re capable of righting certain wrongs. We might be all alone in the world, en effet, but that doesn’t mean we have to be lonely.” She stopped me again, and now we were at the edge of the small park across from her house, the canal that cut across the middle sluggish and choked with cattails, the far bank studded with juniper. “So?

What do you say?”

“To what?”

She put out her hand, palm flat. “Blood sisters.” She wiggled her fingers. “I saw you fiddling with a pin in your hem earlier. Hand it over.”

“I don’t know,” I began, startled. It must be clear by now: I had never met anyone like her.

“Sure you do.” She gave me another one of her smiles.

“Come on, Becky. In or out.”

I hated being called that, but I didn’t dare tell her. She was looking at me closely, her eyes darkened to something like charcoal; after a moment’s hesitation I reached down and undid the latch on the pin, dropping it in her hand.

“Good girl! Now.” She closed her eyes. “Do you solemnly swear?”

She pricked her own finger, then mine. At first I was too busy watching the drops ofblood form on our fingertips and worrying about staining my blouse to hear much of what she said: I remember that she kept her eyes closed as we pressed our index fingers together, her voice solemn as she recited our vows. At a certain point I shut my eyes too, more to shut out the glare of the sun than anything. But as I stood there in the afternoon heat with the sharp scent of juniper filling my nose, I realized with a start that I was happy. That the world might fall to pieces and I wouldn’t care, not the littlest bit.

Autobiography of Us

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 1250044057

- ISBN-13: 9781250044051