Excerpt

Excerpt

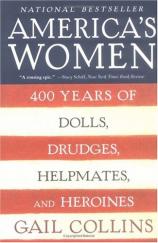

America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines

Chapter One

The First Colonists:

Voluntary and Otherwise

The Extremely Brief Story of Virginia Dare

Eleanor Dare must have been either extraordinarily adventurous or easily led. In 1587, when she was pregnant with her first child, she set sail across the Atlantic, headed for a continent where no woman of her kind had ever lived, let alone given birth. The only English-speaking residents of the New World at the time were a handful of men who had been left behind during an earlier, unsuccessful attempt at settlement on Roanoke Island, in what is now Virginia. Eleanor's father, John White, was to become governor of the new colony. Her husband, Ananias, a bricklayer, was one of his assistants.

Under the best of circumstances, a boat took about two months to get from England to the New World, and there were plenty of reasons to avoid the trip. Passengers generally slept on the floor, on damp straw, living off salted pork and beef, dried peas and beans. They suffered from seasickness, dysentery, typhoid, and cholera. Their ship could sink, or be taken by privateers, or run aground at the wrong place. Even if it stayed afloat, it might be buffeted around for so long that the provisions would run out before the travelers reached land. Later would-be colonists sometimes starved to death en route. (The inaptly named Love took a year to make the trip, and at the end of the voyage rats and mice were being sold as food.) Some women considered the odds and decided to stay on dry land. The wife of John Dunton, a colonial minister, wrote to him that she would rather be "a living wife in England than a dead one at sea."

But if Eleanor Dare had any objections, they were never recorded. She and sixteen other women settlers, along with ninety-one men and nine children, encountered no serious problems until they stopped to pick up the men who had been left at Roanoke. When they went ashore to look for them, all they found were the bones of a single Englishman. The uncooperative ship's captain refused to take them farther, and they were forced to settle on the same unlucky site.

Try to imagine what Eleanor Dare must have thought when she walked, heavy with child, through the houses of the earlier settlers, now standing empty, "overgrown with Melons of divers sortes, and Deere within them, feeding," as her father later recorded. Eleanor was a member of the English gentry, hardly bred for tilling fields and fighting Indians. Was she confident that her husband the bricklayer and her father the bureaucrat could keep her and her baby alive, or was she beginning to blame them for getting her into this extremely unpromising situation? All we know is that on August 18, the first English child was born in America and christened Virginia Dare -- named, like the colony, in honor of the Virgin Queen who ruled back home. A few days later her grandfather boarded the boat with its cranky captain and sailed back to England for more supplies, leaving Eleanor and the other settlers to make homes out of the ghost village. It was nearly three years before White could get passage back to Roanoke, and when he arrived he discovered the village once again abandoned, with no trace of any human being, living or dead. No one knows what happened to Eleanor and the other lost colonists. They might have been killed by Indians or gone to live with the local Croatoan tribe when they ran out of food. They were swallowed up by the land, and by history.

The Dares and other English colonists who we call the first settlers were, of course, nothing of the sort. People had lived in North America for perhaps twenty millennia, and the early colonists who did survive lasted only because friendly natives were willing to give them enough food to prevent starvation. In most cases, that food was produced by native women. Among the eastern tribes, men were generally responsible for hunting and making war while the women did the farming. In some areas they had as many as 2,000 acres under cultivation. Former Indian captives reported that the women seemed to enjoy their work, tilling the fields in groups that set their own pace, looking after one another's youngsters. Control of the food brought power, and the tribes whose women played a dominant role in growing and harvesting food were the ones in which women had the highest status and greatest authority. Perhaps that's why the later colonists kept trying to foist spinning wheels off on the Indians, to encourage what they regarded as a more wholesome division of labor. At any rate, it's nice to think that Eleanor Dare might have made a new life for herself with the Croatoans and spent the rest of her life working companionably with other women in the fields, keeping an eye out for her daughter and gossiping about the unreliable men.

"FEDD UPON HER TILL HE HAD CLEAN DEVOURED ALL HER PARTES"

Jamestown was founded in 1607 by English investors hoping to make a profit on the fur and timber and precious ore they thought they were going to find. Its first residents were an ill-equipped crew of young men, many of them the youngest sons of good families, with no money but a vast sense of entitlement. The early colonists included a large number of gentlemen's valets, but almost no farmers. They regarded food as something that arrived in the supply ship, and nobody seemed to have any interest in learning how to grow his own. (Sir Thomas Dale, who arrived in 1611 after two long winters of starvation, said he found the surviving colonists at "their daily and usuall workes, bowling in the streetes.")

America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines

- paperback: 592 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060959819

- ISBN-13: 9780060959814