Excerpt

Excerpt

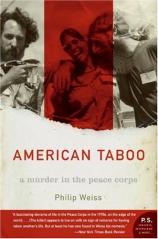

American Taboo: A Murder in the Peace Corps

Chapter One

A Legend of the South Seas

No one forgets his first foreign country. The light, the architecture, the way they do their eggs. Red money. The dreamy disorientation. The smell of aviation fuel.

I didn't choose Samoa, John did. We were both 22 and starting out on a long backpacking trip, and he bought tickets in Los Angeles with six stops down through the Pacific. Samoa was after Hawaii. We got there in January 1978. We stayed at a Mormon family's house in the capital, Apia, climbed through jungle to Robert Louis Stevenson's grave, then set out for the bigger western island. The Peace Corps volunteer was on the ferry, a redheaded guy with half a Samoan marriage tattoo on his back. Of course it turned out Bruce and John had grown up a few miles away from one another in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, so he had us back to his seaside village. We met his Samoan wife Ruta and stayed two or three nights.

It rains harder in Samoa than anywhere. The rain against the metal roof made a throaty song that rose and fell, and under a kerosene lantern, as we dined on one of his chickens, Bruce told us about the murder.

A year or so back in the neighboring country of Tonga, a male Peace Corps volunteer had brutally killed a female volunteer by repeatedly stabbing her. There had been some kind of triangle, a Tongan man was involved. Then the American man was gotten off the island. The case had caused all kinds of tension between the Peace Corps and island governments.

Bruce didn't know more than that, didn't know names or dates. The story had passed from one island to another as stories always did in Polynesia, by word of mouth. The only difference between this story and others was that it involved Americans.

And already then, when I heard the legend in my first foreign country, there was a sense that something was wrong. That the original wrong had been compounded.

Ten years went by. I started working as a journalist in New York, and one night at a bar I met another writer, who said that he had been in the Peace Corps. "Where?" "Tonga. I was in Tonga, the first group of volunteers to the Kingdom."

I asked whether he had heard Bruce's story.

"Oh, yes," Fred said. "Later volunteers told me something. Elsa Mae Swenson, that name comes back. That was the victim."

Her name was Deborah Ann Gardner. The next day in the New York Public Library I found the one article about the case that appeared in the New York Times, an inch or two at the bottom of page 7 in January 1977. The wire story was based on an account from the Chronicle, the government newspaper of Tonga, and said that the male volunteer was from New York and a Tongan jury had found him to be insane when he killed her.

Of course I looked him up in the New York phone book, and there he was. He had been listed from a couple of years after the murder.

I called the Peace Corps. Privacy law would be an important factor in any disclosure. "His rights are basically uppermost at this time," a lawyer explained. So I made a formal request under the Freedom of Information Act, and a few months later a package of old records arrived at my apartment with a lot of the pages blacked out.

Deborah Gardner was 23 and a teacher. She lived in a one-room hut in a village at the edge of the Tongan capital of Nuku'alofa. She had been there nearly ten and a half months when she died in October 1976. The older volunteer charged with her murder faced possible hanging. The American government went to considerable lengths to defend him. A lawyer came from New Zealand and a psychiatrist from Hawaii. It was the longest trial in Tongan memory.

After the insanity verdict, the two governments went back and forth. Then the King of Tonga and his cabinet released the man on written assurance from the Americans that he was to be hospitalized back in the United States.

He refused to enter a hospital. The Peace Corps had lacked the power to make him do so, or the will. The case quietly disappeared.

The key was Deborah Gardner's family. Why had they never come forward? Their names and addresses were blacked out of the file on privacy grounds, and though she was from the Tacoma area, there were hundreds of Gardners listed in the local phone books. I made a few calls and sent a few letters, but before long I got on to something else and, telling myself I would return to this story someday, I put the file away in its big rough brown envelope, put the envelope in a box, and put the box in the attic.

Someday turned out to be 1997. I was hiking with a writer friend when he said that Travel and Leisure magazine was sending him to, of all places, the Kingdom of Tonga because it would be the first country in the world to see sunrise on the millennium and had announced a giant celebration.

"That's funny, I have a Tonga story," I said, and told him about the murder.

Michael stopped in the path. "Why are you working on anything else?"

I dug out the old file and searched for any clues to the identity of Deborah Gardner's family. A fellow volunteer had accompanied her body home. Though the name of the "boy escort" was blacked out on privacy grounds, some of the blackouts were sloppy and it was possible to piece his identity together. Emile Hons of California.

An Emile Hons was listed in San Bruno. I called a few times and left messages, finally got him.

Yes, he'd been in Peace Corps/Tonga. Now he ran the big shopping mall in San Bruno. He was guarded, and questioned my information ...

American Taboo: A Murder in the Peace Corps

- paperback: 416 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 006009687X

- ISBN-13: 9780060096878