Excerpt

Excerpt

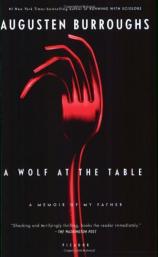

A Wolf at the Table: A Memoir of My Father

Sitting in my high chair, I held a saltine cracker up to my eye and peered through one of the tiny holes, astonished that I could see so much through such a small opening. Everything on the other side of the kitchen seemed nearer when viewed through this little window.

The cracker was huge, larger than my hand. And through this pinprick hole I could see the world.

I brought the cracker to my lips, nibbled off the corners, and mashed the rest into a dry, salty dust. I clapped, enchanted.

The hem of my mother’s skirt. A wicker lantern that hangs from the ceiling, painting the walls with sliding, breathing shadows. A wooden spoon and the hollow knock as it strikes the interior of a simmering pot. My high chair’s cool metal tray and the backs of my legs stuck to the seat. My mother twisting the telephone cord around her fingers, my mouth on the cord, the deeply satisfying sensation of biting the tight, springy loops.

I was one and a half years old.

These fragments are all that remain of my early childhood. There are no words, just sounds: my mother’s breathy humming in my ear, her voice the most familiar thing to me, more known than my own hand. My hand still surprises me at all times; the lines and creases, the way the webbing between my fingers glows red if I hold up my hand to block the sun. My mother’s voice is my home and when I am surrounded by her sounds, I sleep.

The thickly slippery feel of my bottle’s rubber nipple inside my mouth. The shocking, sudden emptiness that fills me when it’s pulled away.

My first whole memory is this: I am on the floor. I am in a room. High above me is my crib, my homebox, my goodcage, but it’s up, up, up. High in the air, resting upon stilts. There is a door with a knob like a faceted glass jewel. I have never touched it but I reach for it every time I am lifted.

Above my head is a fist of brightness that stings my eyes. The brightness hangs from a black line.

I am wet-faced and shrieking. I am alone in the awake-pit with the terrible bright above my head. I need: my mother, my silky yellow blanket, to be lifted, to be placed back in my box. I am crying but my mother doesn’t come to pick me up and this makes me mad and afraid and mad again, so I cry harder.

On the other side of the door, he is laughing. He is my brother. He’s like me but he’s not me. We’re linked somehow and he’s home but he’s not home, like my mother and her voice.

Opposite this door against the wall, there is a dresser with drawers that my mother can open but I cannot, no matter how hard I pull. The scent of baby powder and Desitin stains the air near the dresser. These smells make me want to pee. I don’t want to be wet so I stand far away from the dresser.

This is my first whole memory—locked alone in my room with my brother on the other side of the door, laughing.

There is another memory, later. I am in the basement sitting on a mountain of clothing. The washer and dryer are living pets; friendly with rumbling bellies. My mother feeds them clothing. She is lifting away pieces of my mountain, placing them into the mouth of the washer. Gradually, my mountain becomes smaller until I can feel the cool of the cellar floor beneath me.

A form on the wooden stairs. The steps themselves smell sweet and I like to lick them but they are coarse and salty; they don’t taste as they smell and this always puzzles me and I lick again, to make sure. The thing on the stairs has no face, no voice. It descends, passes before me. I am silent, curious. I don’t know what it is but it lives here, too. It is like a shadow, but thick, somehow important. Sometimes it makes a loud noise and I cover my ears. And sometimes it goes away.

“Did my father live with us at the farmhouse in Hadley?”

I was in my twenties when I called my mother and asked this question. The farmhouse—white clapboard with black shutters and a slate roof—sat in a brief grassy pasture at the foot of a low mountain range. I could remember looking at it from the car, reaching my fingers out the window to pluck it from the field because it appeared so tiny. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t grab it, because it was just right there.

“Well, of course your father lived with us at the farmhouse. He was teaching at the university. Why would you ask that?”

“Because I can remember you, and I can remember my brother. And I can remember crawling around under the bushes at the red house next door.”

“You remember Mrs. Barstow’s bushes?” my mother asked in surprise. “But you weren’t even two years old.”

“I can remember. And the way the bushes felt, how they were very sharp. And there was a little path behind them, against the house. I could crawl under the branches and the dirt was so firm, it was like a floor.”

“I’m amazed that you can remember that far back,” she said. “Though, I myself can also remember certain things from when I was very little. Sometimes, I just stare at the wall and I’ll see Daddy strolling through his pecan orchard before he had to sell it. The way he would crack a nut in his bare hands, then toss those shells over his shoulder and wink like he was Cary Grant.”

“So he was there?” I pressed her.

“Was who where?” she said, distracted now. And I could picture her sitting at her small kitchen table, eyes trained on the river and the bridge above it that were just outside her window, the phone all but forgotten in her hand, the mouthpiece drifting away from her lips. “Yes, he was there.” And then her voice was clear and bright, as though she’d blinked and realized she was speaking on the phone. “So, you don’t remember your father there at all?”

“Just . . . no, not really. Just a little bit of something on the stairs leading to the basement with the washer and dryer and then this vague sense of him that kind of permeated everything.”

“Well, he was there,” she assured me.

I tried to recall something of him from that time; his face, his hands, his memorable flesh. But there was nothing. Trying to remember was like plowing snow, packing it into a bank. Dense whiteness.

I could remember the pasture in front of the house and standing among rows of corn as tall as trees. I could remember the smell of the sun on my arms and squatting down to select pebbles from the driveway.

I could remember how it felt to rise and rise and rise, higher than I’d ever gone before as my trembling legs continued to unfold and suddenly, I was standing and this astounded me and I burst out laughing from the pure joy of it. Just as I threatened to fall on my face, my leg swung forward and landed, and so fast it seemed to happen automatically, my other leg swung forward and I did it again—my first step!—before tumbling forward onto my outstretched hands.

But I could remember nothing of my father.

Until years later, and then I could not forget him no matter how hard I tried.

A Wolf at the Table: A Memoir of My Father

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 0312428278

- ISBN-13: 9780312428273